Congress waited too long to start securing the 2020 elections

After the US House and Senate passed a $1.4 trillion spending package this week, lawmakers on both sides of the aisle congratulated themselves, which funds the federal government through September. It adds nearly $2 billion in additional funding for fighting wildfires, sets aside $25 million for gun violence research, and apportions $7.6 billion for the 2020 Census.

After the US House and Senate passed a $1.4 trillion spending package this week, lawmakers on both sides of the aisle congratulated themselves, which funds the federal government through September. It adds nearly $2 billion in additional funding for fighting wildfires, sets aside $25 million for gun violence research, and apportions $7.6 billion for the 2020 Census.

Under the terms of the deal, all 50 states will also receive funding to improve election security. But according to Lawrence Norden, director of the Election Reform Program at the Brennan Center for Justice at New York University School of Law, securing the 2020 elections from top to bottom require more time and money than what has been allocated thus far.

“Congress has been completely absent when it comes to funding for election security,” Norden told Quartz. “For the most part, Congress has said, ‘States, it’s up to you,’ and states have said, ‘Counties, it’s up to you,’ and election security has been neglected.”

Congress voted to distribute $425 million among the states. A provision calls for states to match an additional 20% of the amount received within two years, bringing the eventual funding for election security to about $500 million nationwide. Last year, Congress also earmarked $380 million for states to strengthen election security. State governments have until October 2023 to spend it all.

Prior to 2018, the last time Congress earmarked funds for election security was in 2002. Over the course of those 16 years, Norden said American election infrastructure deteriorated, failing to evolve alongside the evolving threats. The millions of dollars granted to states this week covers only about half of what experts say is needed just to protect against cyberattacks, and a fraction of the nearly $2.2 billion necessary to outfit the broader US election system with basic security essentials over the next five years.

Many voters would agree that after the 2016 election, securing the democratic process in the United States is of paramount importance. The Senate Intelligence Committee found that in 2016 Russian hackers undertook an “unprecedented level of activity against state election infrastructure,” targeting election networks across the country. Authorities expect similar efforts by Russia and others during the 2020 elections, and although US president Donald Trump has shrugged off the warnings, everyone from the FBI to Facebook believes ongoing election interference constitutes a serious threat.

Yet today, at least 40 states are still using decade-old electronic voting systems, some of which are so outdated election officials have to buy replacement parts on eBay. Senator Amy Klobuchar, a Minnesota Democrat running for president, said that eight states will be using electronic voting machines that leave no physical paper trail, making it impossible to verify the results if there are discrepancies.

What’s really needed is a “consistent, steady stream of funding for election security that states and local election officials can plan around,” Norden said. “It’s a race without a finish line, and very hard to plan long-term when you don’t know what the next step is going to be.”

Beyond a lack of sufficient financing, election systems are primarily overseen by state and local authorities and are not subject to any meaningful federal regulations or oversight. Private companies are responsible for almost everything in US elections, from creating the registration databases that list who is eligible to vote, to programming the machines that count people’s votes, Norden said.

Manufacturers of voting machines are not required to report foreign ownership or control, nor are they obligated to patch faulty software or secure their physical infrastructure. These vendors are also not required to perform background checks on employees, system testing only occurs at the end of the manufacturing process, and doesn’t ensure that vendors adhere to proper supply chain or cybersecurity controls during development, programming, or deployment phases.

“There is a supposition on the part of a lot of people opposed to machine-marked ballots that you could have a significant number of ballots changed by the machine and people wouldn’t notice,” Norden said. “I certainly think we should get rid of paperless machines, but we will have about 16 million people voting on paperless machines in 2020.”

Some degree of comfort might be taken in knowing that, according to Norden, “very few” of those 16 million votes will be cast in battleground states.

The newly allocated money will allow states to hire extra cybersecurity staff, and build more robust resiliency plans in case there is a successful hack. Of the 8,000 separate election jurisdictions across the country, the counties with systems hit by hacking attempts in 2016 were usually the ones with the least resources, Norden said.

Are we ready?

With such decentralized voting infrastructure, Norden assumes there will be “some” successful intrusions.

“The question is, what do you do about it?” he asked. “Are we ready for that?”

Election systems in every US state will use sensors meant to detect hacking attempts, but they have limits. Beyond cyberattacks, researchers have run tests simulating everything from blackouts engineered to suppress votes, to broad disinformation campaigns powered by deep-fake audio and video, to physical attacks at polling stations.

This, Norden said, is where resiliency planning is especially important. In the event of a blackout, is there another way for people to vote? Are backup generators available? Is there a plan for emergency paper ballots? What about a plan for how and where those paper ballots are stored?

“Election officials have long done this kind of contingency planning but it’s important for them to rethink those plans in light of new threats,” Norden said. “Do we have enough redundancies in place so that if systems are attacked, people can vote and we can count their votes?”

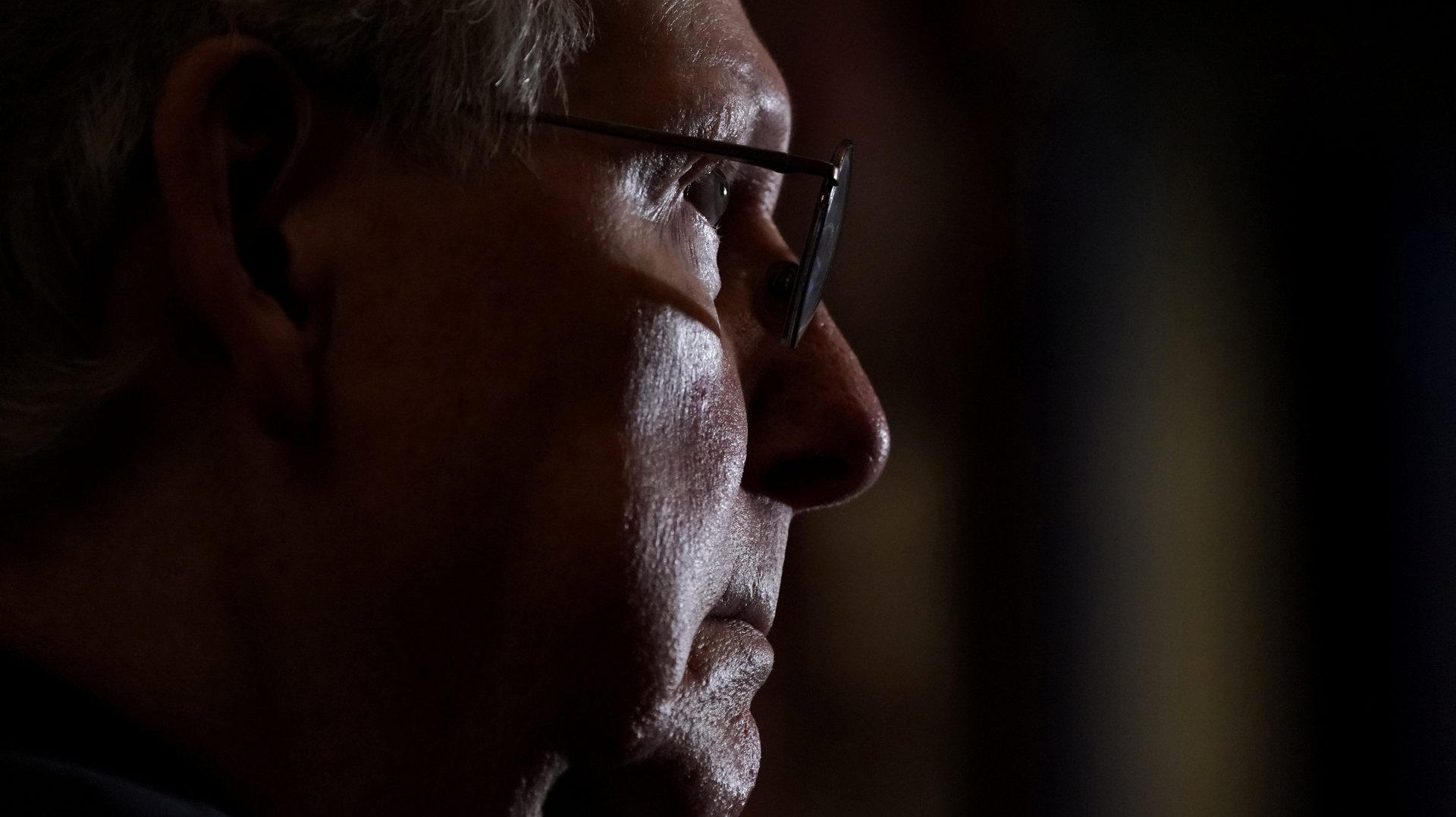

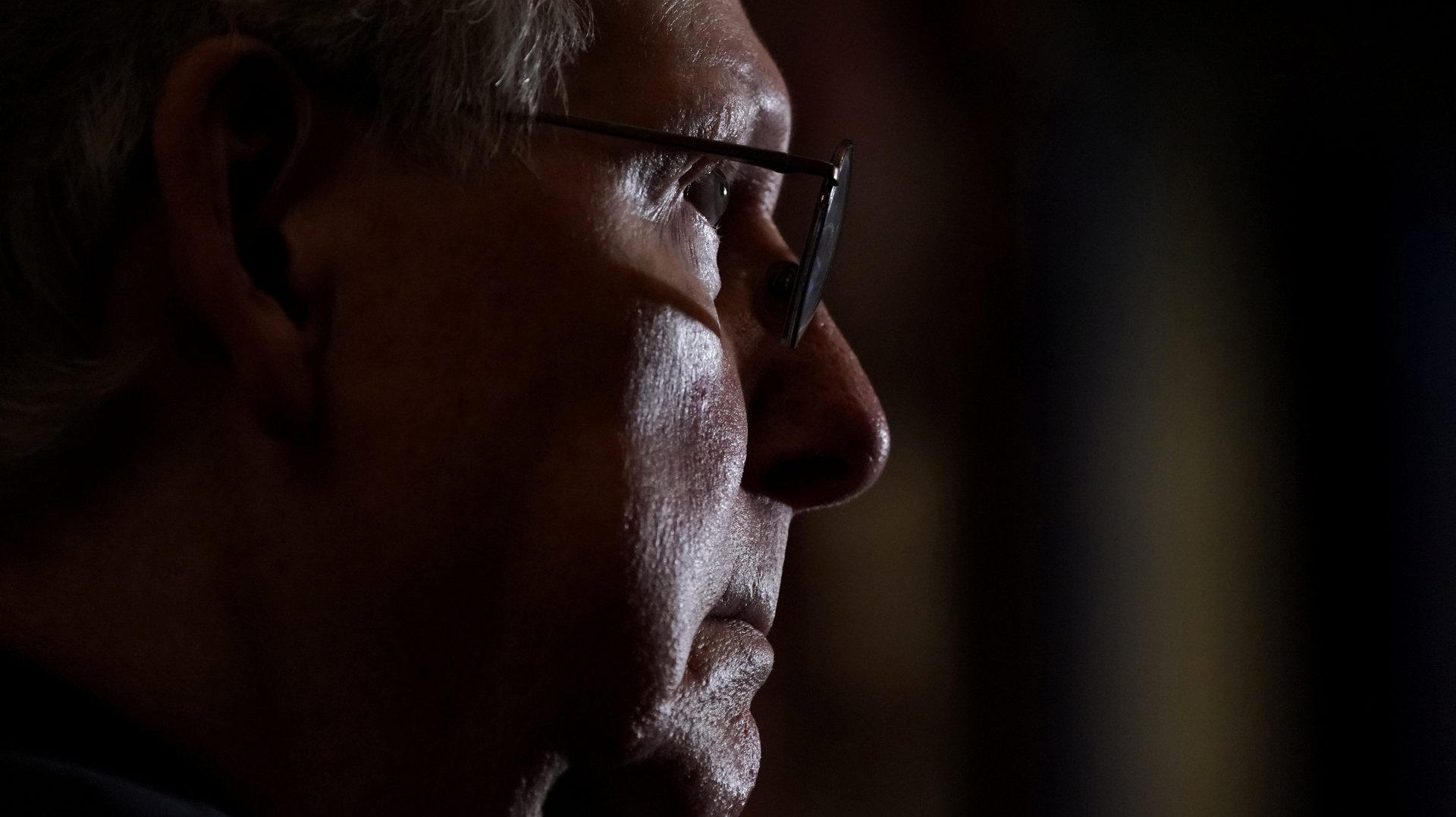

In the three years since the 2016 election, Norden said Republican congressional leaders have “not seen themselves as partners” in the election security process.

“I don’t think there’s any two ways about it,” he said. “If you look at where there have been proposals for election security, they have died in the [GOP-controlled] Senate, and Mitch McConnell and the Republican majority have not moved any of their own proposals around election security that are of any significance, given the level of the threat.”

This week’s budget agreement will provide each state with the following amounts for election security, based on each state’s voting-age population, according to the Brennan Center: