To be a better ally, I gave up reading books by men for 2019

Let me start with a confession: I’m a British man in my late 20s, have a literature degree and consider myself a feminist—but until summer 2018, I had never read a Jane Austen novel. Or a Charlotte Bronte novel. Or, indeed, an Emily Bronte novel.

Let me start with a confession: I’m a British man in my late 20s, have a literature degree and consider myself a feminist—but until summer 2018, I had never read a Jane Austen novel. Or a Charlotte Bronte novel. Or, indeed, an Emily Bronte novel.

A lazy holiday forced me, finally, to confront the gender gap in my reading history. I found a copy of Pride and Prejudice in the house where I was staying, and decided “not really liking 19th century literature” was no longer an excuse. I’d read a fair chunk of Dickens, after all.

I was lost to my fellow vacationers for the next two days, delighting in Austen’s peerless prose.

Returning home, I studied my bookshelf and found the authors were diverse in terms of race and sexuality but only about 25% to 30% were female. A terrible return—even taking into account the white-male-dominated (and alarmingly designed) titles I have to read for my job covering global corruption and authoritarianism.

Something needed to change. I resolved not to read a single novel by a man in 2019.

Some male friends—normally enlightened feminists—were defensive. “Around 60% of the books I’ve read this year are by women, but I don’t see the need to cut out men entirely,” said a friend who is conscious about gender-balanced reading.

In some ways, he was right—I could have reached parity by just reading more female authors. But the decision wasn’t about hard data. I wanted to dramatically change the way I choose, and think about, books.

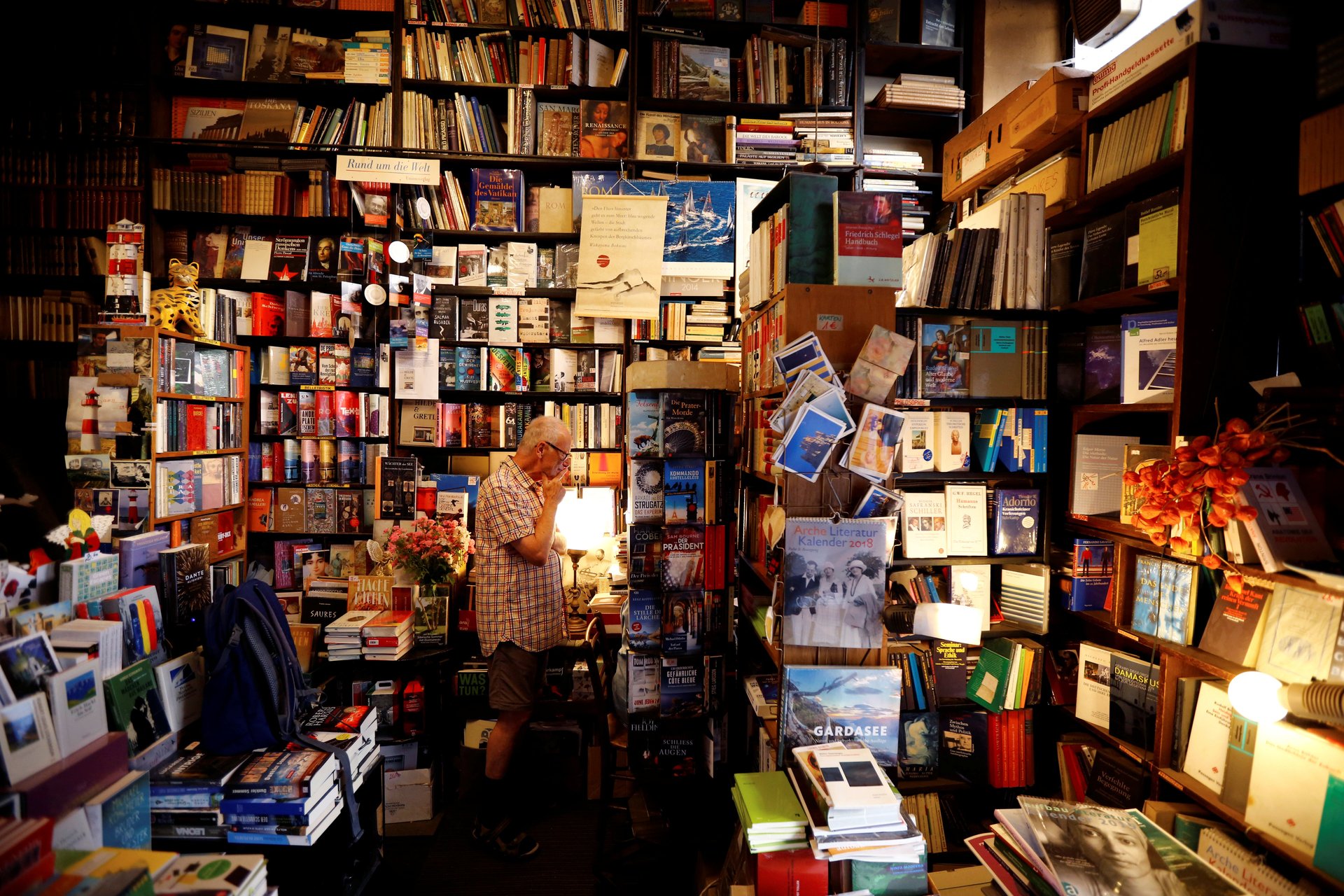

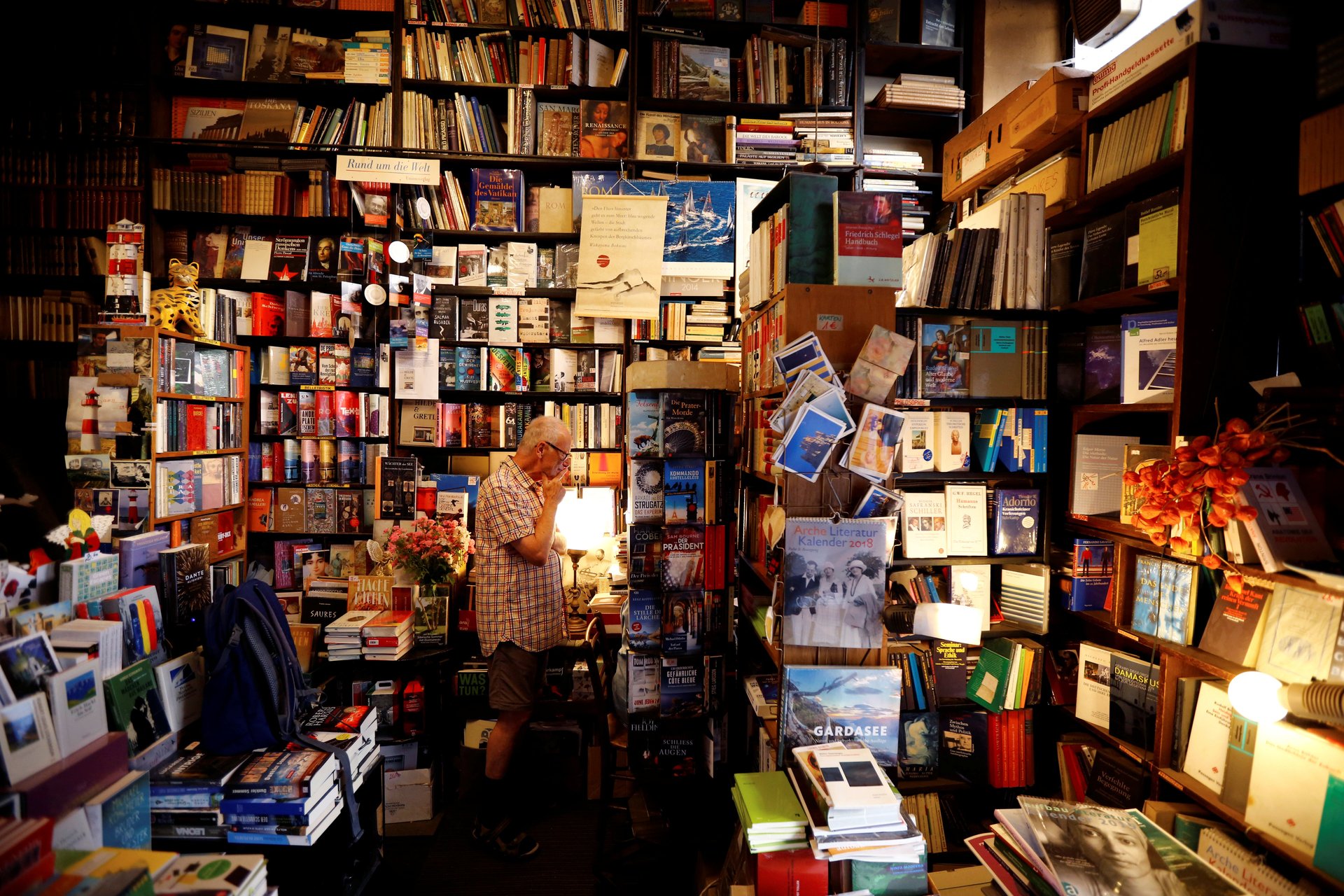

That meant casting out habits picked up over nearly three decades of patriarchal socialization. Before my resolution, there’s little chance that, out of the “18 miles of books” in New York’s storied Strand bookstore, I would have made a beeline towards a novel marketed as “the black Bridget Jones.” This time, I instantly picked up Candice Carty-Williams’ Queenie.

Glancing at the book on the subway home jogged a childhood memory. As a 13-year-old, I zoomed merrily through my stepmum’s copy of Bridget Jones’s Diary. I was drawn in by Bridget’s vivid, human voice; by author Helen Fielding’s use—then new to me—of diary as literary form; and by experiencing a life entirely alien to me. But my joy was colored by a lingering unease: I knew teenage boys weren’t supposed to be reading this sort of book.

Soon after, I was at lunch with family and friends. Someone said, with the gentlest hint of derision, “Max has been reading Bridget Jones!” The table turned as one to look at me.

“Really?!” a family friend smiled.

My skin prickled into a hot blush. “What’s wrong with that? It’s an interesting book,” I mumbled.

She attempted a kind explanation. “Well, it’s more a question of how you could have anything in common with a woman in her early 30s struggling with singledom.”

Only seeking perspectives you already know is, of course, far from the point of reading literature. But my 13-year-old self didn’t know that.

My family friend wasn’t acting out of malice. Like all of us, she was playing her part in a system that feminist theorist bell hooks calls the “white-supremacist capitalist patriarchy.” The system holds that straight white men are the social norm. Anyone who transgresses that norm by refusing to follow traditional gender stereotypes is viewed askance and, in small and large ways, treated as an outcast. We are all faced with a choice of how to deal with it: speak out and put up with the alienation, or adapt and bury your true self. When I got home after that lunch, I stowed away the sequel, Bridget Jones: The Edge of Reason, and never finished reading it.

In the literary world, this norm’s most tangible effect is on female and gender-queer writers. Between 1950 and 2016, there was only one year where the number of books by female authors on The New York Times bestsellers list equalled those by men. The women who manage to sell their books do so on average at almost half the price of their male counterparts. Unsurprisingly, female authors can struggle to get their books picked up by publishers. After pitching her book to 50 publishers and getting just two manuscript requests, writer Catherine Nichols created a male pseudonym, pitched the same book 50 times and had 17 manuscript requests. “He is eight and a half times better than me at writing the same book,” she wrote in a 2015 piece for Jezebel. There’s little available data on the treatment of trans writers, but non-binary authors wrote less than 0.5% of the articles featured last year in 15 of the biggest English-language literary publications.

But the problem goes much deeper than the book market. The fight for gender equality needs buy-in from men who, as humans, tend to be moved by stories rather than data.

By siloing men from all novels by women that aren’t deemed “great” literature by the often-sexist world of literary criticism, we bar them from crucial insights into how the patriarchy affects women.

My experience reading Queenie is a case in point. Where Bridget Jones showed me an alien world, Queenie is set in the world I inhabit. It’s about a millennial (like me) from southeast London (where I grew up) working in the media, but experienced from the perspective of a black woman. Before reading the book, I knew intellectually that black women suffer from extraordinary levels of sexualization—whether verbal, subtle, aggressive, or physical. But only after experiencing that relentless barrage of harassment from inside Queenie’s head could I really begin to understand the exhausting psychological toll it must take on my friends and colleagues.

Queenie pairs well with Adelle Waldman’s brutal Love Affairs of Nathaniel P.. A precursor to today’s “softboys,” Waldman’s anti-hero, up-and-coming writer Nate, exemplifies the would-be progressive male intellectuals who pay lip service to feminism while merrily enjoying and perpetuating the misogyny of the literary world. For any decent man with a modicum of self-awareness, it’s an excruciating read: In Nate, we see the embodiment of all the worst things we say, think, or do. In books like Queenie, we see and feel some of the consequences.

But my resolution wasn’t a self-righteous, self-prostrating chore. It was a joy. I reveled in a plethora of wonderful authors whom I’ve ignored for so long, racing through canonical writers like Joan Didion, Andrea Levy, and Eve Babitz, and contemporary ones, like Kamila Shamsie, Jhumpa Lahiri, and Lauren Groff. Looking for an easy comedy to lighten my mood, I turned not to my usual retreat, P.G. Wodehouse, but to Nora Ephron. Where Wodehouse tells somewhat vacuous stories in exquisite comic prose, Ephron brings wisdom and insight along with the laughs. (I also found myself making the cabbage strudel recipe she spent decades searching for.)

Being forced to go beyond the authors—both male and female—who grab the plaudits and headlines can yield great treasures. Wanting to indulge a new-found obsession with trees, I didn’t open Richard Powers’ acclaimed The Overstory, but the little-known Semiosis by Sue Burke. It turned out to be the best sci-fi novel I’ve ever read. Her tale of humans starting afresh on a planet with super-advanced flora is a searingly intelligent reflection on everything from the nuclear family to the surveillance state. It also gripped me in a deep, all-encompassing way that few books have done since I was a kid. However, while The Overstory won a Pulitzer and Powers is a MacArthur fellow, Semiosis is marketed with lines like, “A fascinating world,” from The Verge.

In the midst of all this, I have to admit: I cheated. Once. On holiday in Vietnam, I couldn’t find any English language copies of the sole female Vietnamese author I’d been recommended, and let myself enjoy Graham Greene’s The Quiet American. The pleasure was hollow. Despite Greene’s apparently earnest attempts to confront what Edward Said later called orientalism, there’s no escaping that his main female character is an exoticized shell.

That wasn’t the only way I let myself down. Despite my early intentions, I’ve read just one gender-queer author (Andrea Lawlor’s terrific Paul Takes the Form of a Mortal Girl). I haven’t got to 19th century greats like Edith Wharton, George Eliot, and the Brontes. And the books I’ve read are almost exclusively by Europeans or Americans.

But I’m okay with having fallen short. All men are imperfect feminists. We screw up constantly, and most of the time don’t even realize it. For me, being a male feminist is about catching as many mistakes as you possibly can and doing your best to redress them. It’s a constant cycle of striving and failing, recognizing that failure and picking yourself up to strive again.

I’ll try to fill those reading gaps next year.