Twelve works of art that chart the emotional upheavals of the Hong Kong protests

The renowned John Elderfield, chief curator emeritus of painting and sculpture at The Museum of Modern Art in New York, wrote: “Truly political art […] does not reduce human affairs to slogans; it complicates rather than simplifies.”

The renowned John Elderfield, chief curator emeritus of painting and sculpture at The Museum of Modern Art in New York, wrote: “Truly political art […] does not reduce human affairs to slogans; it complicates rather than simplifies.”

While the vivid slogan-driven protest art seen on the streets of Hong Kong, and shared via apps have become new icons of the city’s visual culture, the complexity of the biggest political crisis the city has ever seen demands deeper artistic reflection and investigation. Many Hong Kong artists produced or exhibited works in 2019 that offer insights into the emotional roller coaster the city has experienced since protests erupted in June. Some even appear to have foreseen some aspects of the upheavals of the past seven months, as the protests deepened into a political movement for Hong Kong’s rights and freedoms.

Unlike the street art Hong Kong’s movement has generated, the works below often do not contain literal motifs representing recent events, yet brought together, they offer layered readings of our current situation.

Part I: Happiness in Hong Kong is just a facade

There is no better way to begin the story with the creepy fake laughter from young Hong Kong artist Mak Ying Tung 2’s multi-screen video installation Fake Laugh that was shown at the de Sarthe Gallery in Hong Kong this fall. For how long have we been pretending that life in Hong Kong is perfect and happy, despite undercurrents of unease about Beijing’s interference in Hong Kong?

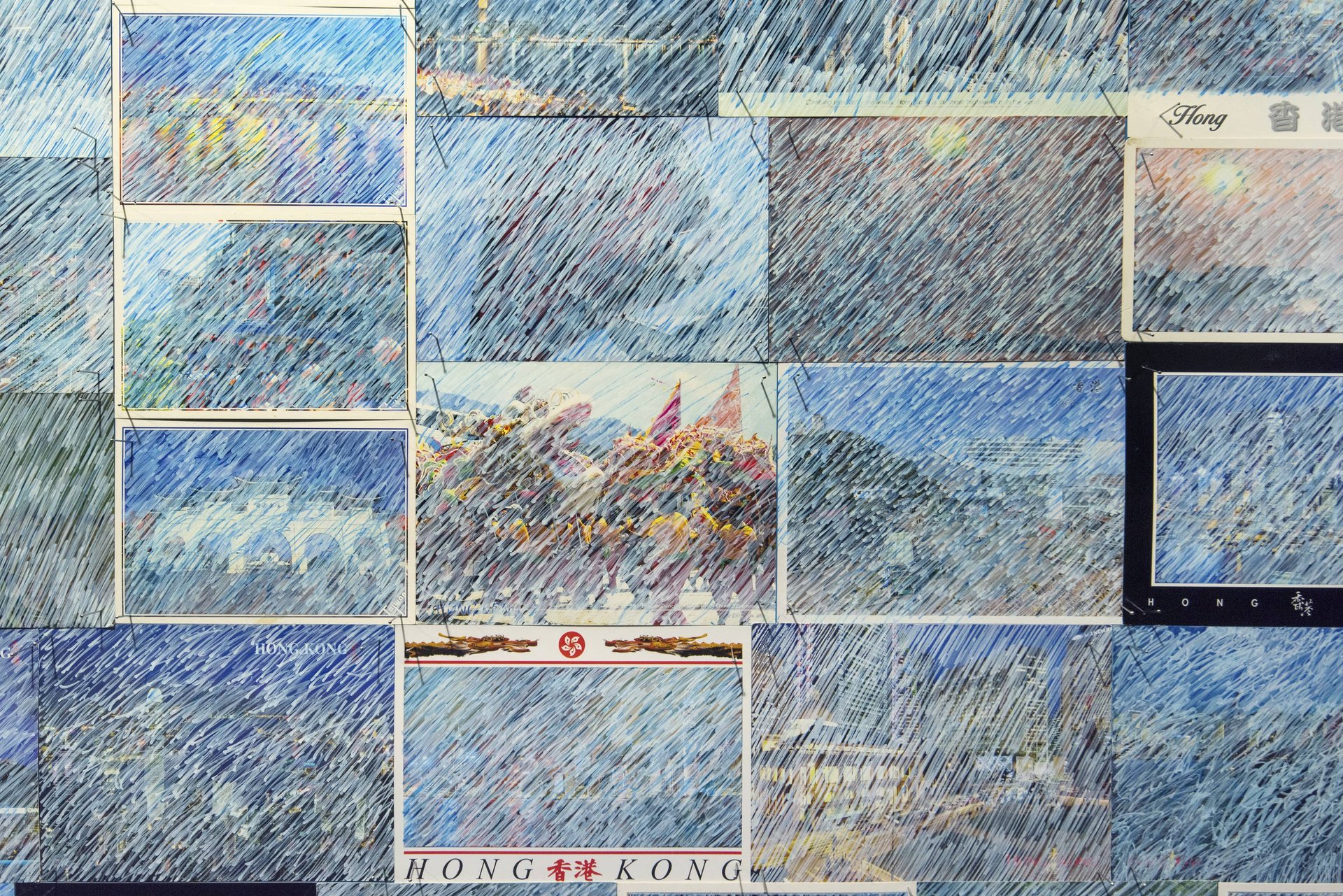

This is echoed by a observation from Ching, a Hong Kong artist who is known for his socially-engaged conceptual works: Why is Hong Kong always under a sunny blue sky in postcards when nearly 40 per cent of the year is rainy? The raindrops Ching painted on the 721 postcards exhibited at Hong Kong’s Blindspot Gallery in September are like sharp needles piercing through this Hong Kong bubble.

Part II: Will history repeat itself on the frontlines of Hong Kong’s protests?

The Execution of Maximilian (1868-69) by Édouard Manet and Liberty Leading the People (1830) by Eugène Delacroix are two important political paintings executed in response to historical events occurring at the time of their creation.

Referencing these two Western classics, Hong Kong artist and illustrator Justin Wong, and anonymous illustrator Harcourt Romanticist, created contemporary versions set against the backdrop of Hong Kong protests. While Our Vantage is obviously inspired by Delacroix’s commemoration of the July Revolution in 1830, The Execution of Maximilian has a more complicated story: the young Austrian-born Archduke Ferdinand Maximilian Joseph, who was installed as the emperor of Mexico in 1864 to create a monarchy with the backing from Napoleon III, was executed by the Mexican government opposing his rule after the French army withdrew. Manet was said to have begun working on the painting as soon as the news traveled back to France, based on news clippings and other documentary sources.

The work has been widely interpreted as Manet’s political statement against French colonial rule. The painting has also been compared to Francisco de Goya’s The Third of May 1808, a work in which the faceless French troops executing Spanish rebels can be seen today as a symbol of state tyranny. In Wong’s version, the executioners wear the blue uniforms of Hong Kong police, seen by many to be closer to Beijing than to the city’s own residents.

Part III: Police brutality is no longer a surreal imagination

Hong Kong has witnessed once unthinkable scenes in recent months. Tear gas and rubber bullets met Molotov cocktails in the streets, battle scenes unfolded in malls, and university campuses became war zones. Artists have a way of articulating the anxiety of a Hong Kong where a reality that appears increasingly surreal makes it hard to know what or whom to believe.

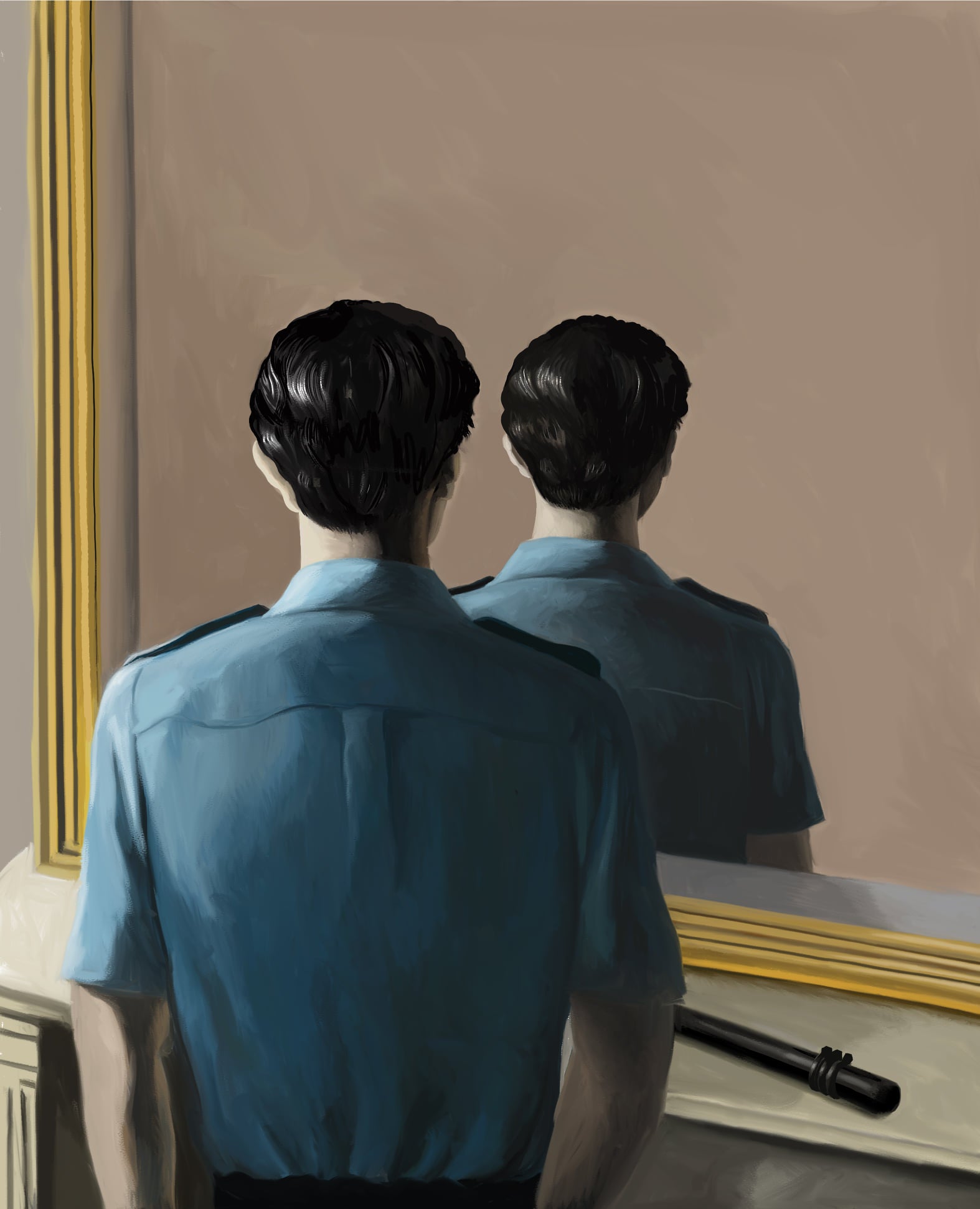

Belgian surrealist Rene Magritte was a source of inspiration for two works by Wong and illustrator Pon’Seed that both depict distrust of the police, now widespread in Hong Kong. Drawing on Not to Be Reproduced (1937), Wong painted an image of a police officer who fails to see who he is as the mirror only reflects the rear image of the police officer.

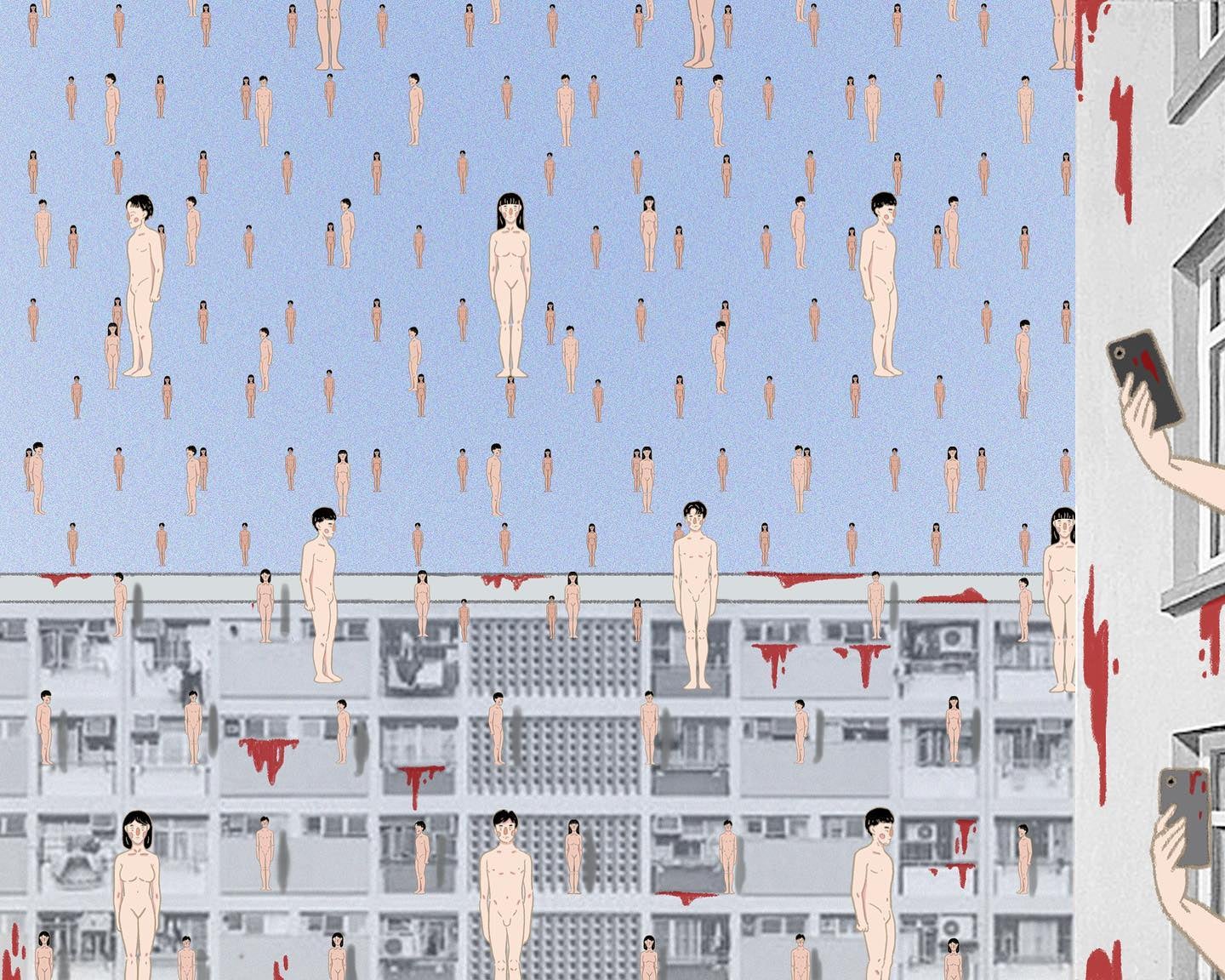

Pon’Seed’s depressing take on Magritte’s Golconda (1953) replaces the raining men in suits and bowler hats in the original painting with naked bodies falling from the sky, a reference perhaps to the rumors and suspicions that have flourished around the death of a teenage girl, and other similar incidents.

In the case of Hong Kong sound artist Samson Young and multimedia performance artist Isaac Chong Wai, their artistic visions of the future seem to have been prophetic.

Young’s performative sound installation Canon debuted in 2016 and the current edition is on show at Gropius Bau in Berlin. The artist dresses up as a Hong Kong policeman from the British colonial era, holding a Long Range Acoustic Device, or LRAD, a non-lethal sonic weapon, beaming concentrated sound or birdcalls at his audience. The work intends to metaphorically explore how sound can be used as a weapon and a tool of state control against the backdrop of Hong Kong geopolitical complications but when police deployed an LRAD, during one of the clashes in November, Young’s imagination became reality.

Chong, meanwhile, investigates police violence through his video work Rehearsal of the Futures: Police Training Exercises in which he choreographs dancers dressed in riot police uniforms performing their duties of charging and subduing protesters in ultra-slow motion.

Commissioned last year by M+, Hong Kong’s mammoth visual culture museum in-the-making, located in West Kowloon Cultural District, and exhibited at Blindspot Gallery in March, by framing police brutality as poetic dance movements, the video work questions structural violence. Now looking back, Berlin-based Chong was genuinely rehearsing the future for us as reports of questionable use of force by the police have become daily news in not just Hong Kong but also around the world.

Humor, sarcasm and cynicism are ways Hongkongers deal with traumatic moments, and Hong Kong artists South Ho and Kacey Wong have injected these elements into their works.

Ho, who has been documenting the protests on the frontline in photographs and videos, questions the police’s use of force in an installation exhibited at Blindspot Gallery in September that consists of what appear to be colorful versions of sponge rounds, a non-lethal weapon often used by riot police. The names of non-lethal weapons like sponge rounds and rubber bullets give people a false impression of these weapons being soft and harmless, when in reality they can cause severe injuries. Ho’s Sponge Round Cake interrogates this kind of use of force.

Wong, meanwhile, has done numerous performative art pieces during the protests and in S.S.T.U. Special Singing Tactical Unit, he dressed as a raptor, Hong Kong police’s special tactical unit. He waved his baton to conduct the crowd at the Hong Kong Way human chain protest on August 23 to sing along protest songs blasting from the loudspeaker he was carrying. At first, the crowd were scared and suspicious. But as they realized the raptor was not real, they happily collaborated. The interactive work played with both the role of singing as a protest tactic, and the public’s distrust in the police.

Part IV: Connecting our roots with the future

“How will this end?” is probably among the most often asked question about Hong Kong protests. No one knows the answer right now, but Lam Tung Pang’s latest video installation, Image-coated, featured at the recently re-opened Hong Kong Museum of Art, reminds us that there is no future without dealing with our past. First, there’s an image of Lu Ting (or sometimes spelt as Lou Ting), a half-fish, half-human mythical creature said to represent the identity of Hong Kong, overlooking Victoria Harbour from over a century ago; opposite this is an image of a man holding a telescope and looking into the distance.

Installed next to a view of Victoria Harbour, the work demands the audience reflect on Hong Kong’s roots and connect them with the present while looking to the future.

And what will the future be? Australia-based Chinese artist Badiucao, who has been tirelessly producing political cartoons chronicling Hong Kong protests, offers his best wishes through Lennon Wall Flag, inspired by the colors of Post-its on the iconic Lennon Walls across the city. This video work captures the flag flying high under a blue sky, as if it were carrying people’s good wishes for Hong Kong written on the colorful notes into a glorious future.