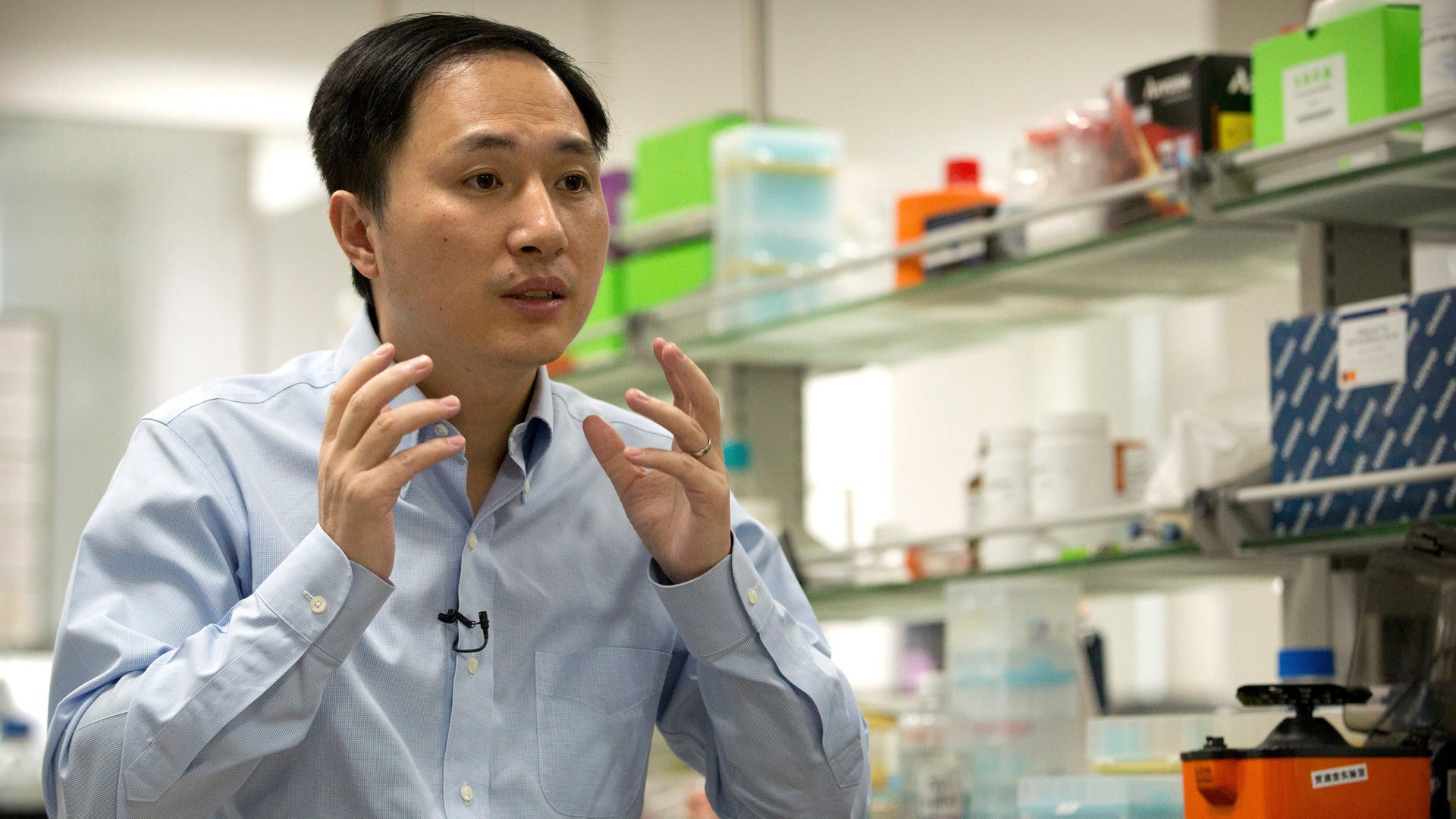

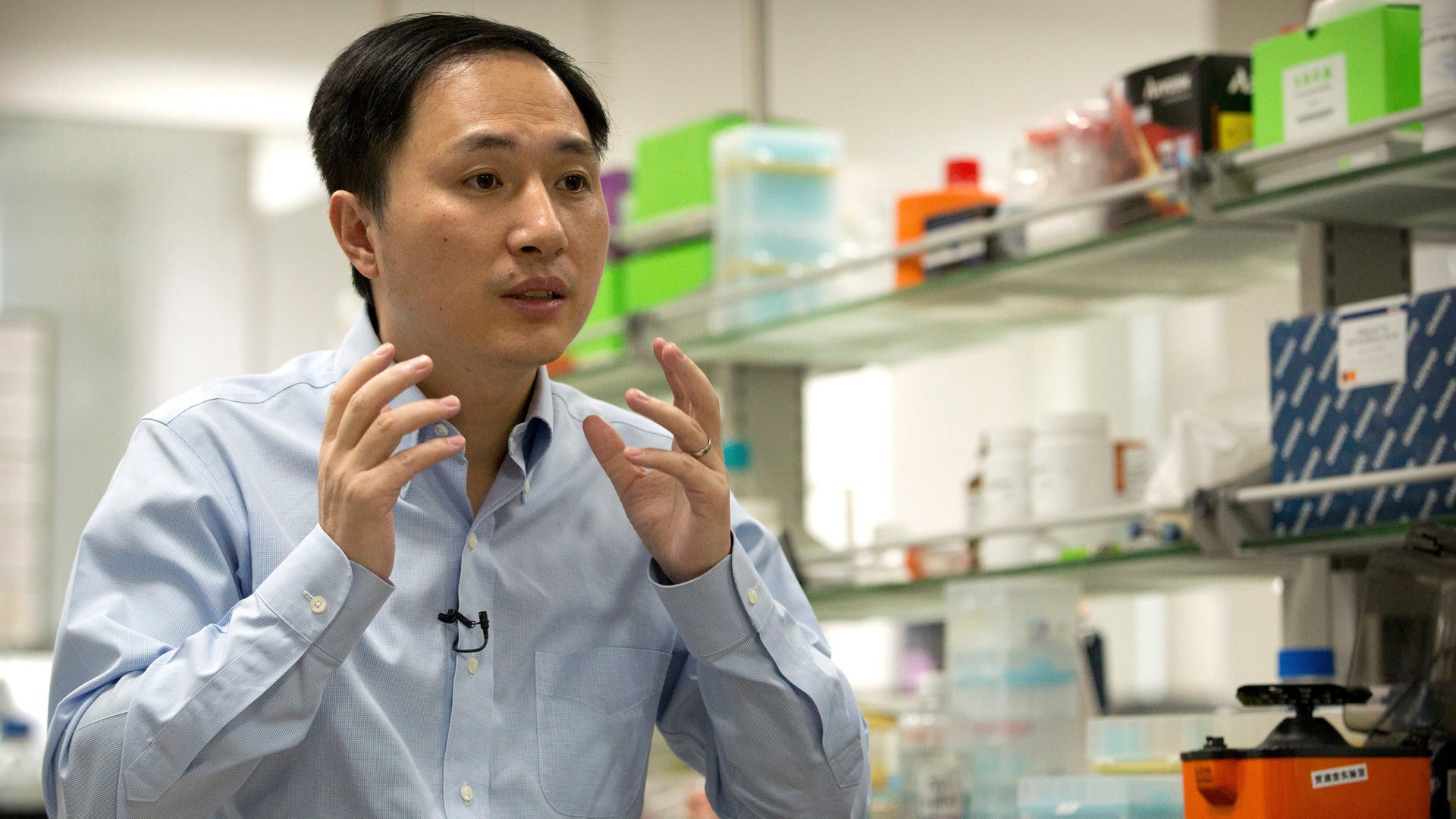

China sentenced the scientist behind the world’s first gene-edited babies

A Chinese court today (Dec. 30) handed a three-year prison sentence to the Chinese scientist who announced a year ago that he had created the world’s first gene-edited babies, sparking global concern that genetic science had entered into a dark new era.

A Chinese court today (Dec. 30) handed a three-year prison sentence to the Chinese scientist who announced a year ago that he had created the world’s first gene-edited babies, sparking global concern that genetic science had entered into a dark new era.

He Jiankui was the lead researcher of experiments that used the CRISPR gene-editing technique on embryos, and that resulted in the births of three babies whose DNA was altered for HIV resistance, according to China’s state-owned Xinhua news agency. The court also fined He, who hasn’t been seen in public since speaking at a genetics conference in Hong Kong last year, three million yuan ($430,000) for carrying out illegal medical practices, including practicing medicine without being qualified to do so and forging ethical review documents (link in Chinese). Two of He’s fellow researchers, who helped him carry out the experiments, received sentences of two years and 18 months in prison.

The behavior of the three “breached the moral bottom line of scientific research and medical ethics,” said the court in southern city Shenzhen, where He’s former employer, the Southern University of Science and Technology is based.

In November last year, MIT Technology Review and the Associated Press revealed the births of genetically-edited Chinese twin sisters Lulu and Nana from He’s experiments. He had recruited seven couples in which the male partner was HIV positive, while the female was not, and had carried out in-vitro fertilization after manipulating the embryos for HIV resistance. He drew criticism globally, and from the Chinese scientific community, for violating guidelines on CRISPR research, which recommended that gene-edited embryos should not be used to establish a pregnancy. Given advances in HIV medicine that can protect offspring from a father’s infection,the value of the health benefits of He’s tampering appeared far outweighed by the risk of unintended consequences.

He said at the conference last year that another woman was pregnant with a gene-edited baby.

Beijing condemned He’s behavior, and tightened its regulations on gene-editing, requiring scientists to get approval from a department under the State Council before they use such “high-risk biomedical technologies.” Despite China’s seemingly harsh stance on the episode, some reports have suggested He’s research might have been funded by three Chinese government institutions, including the country’s science ministry.