China might have funded the Crispr baby experiment it distanced itself from

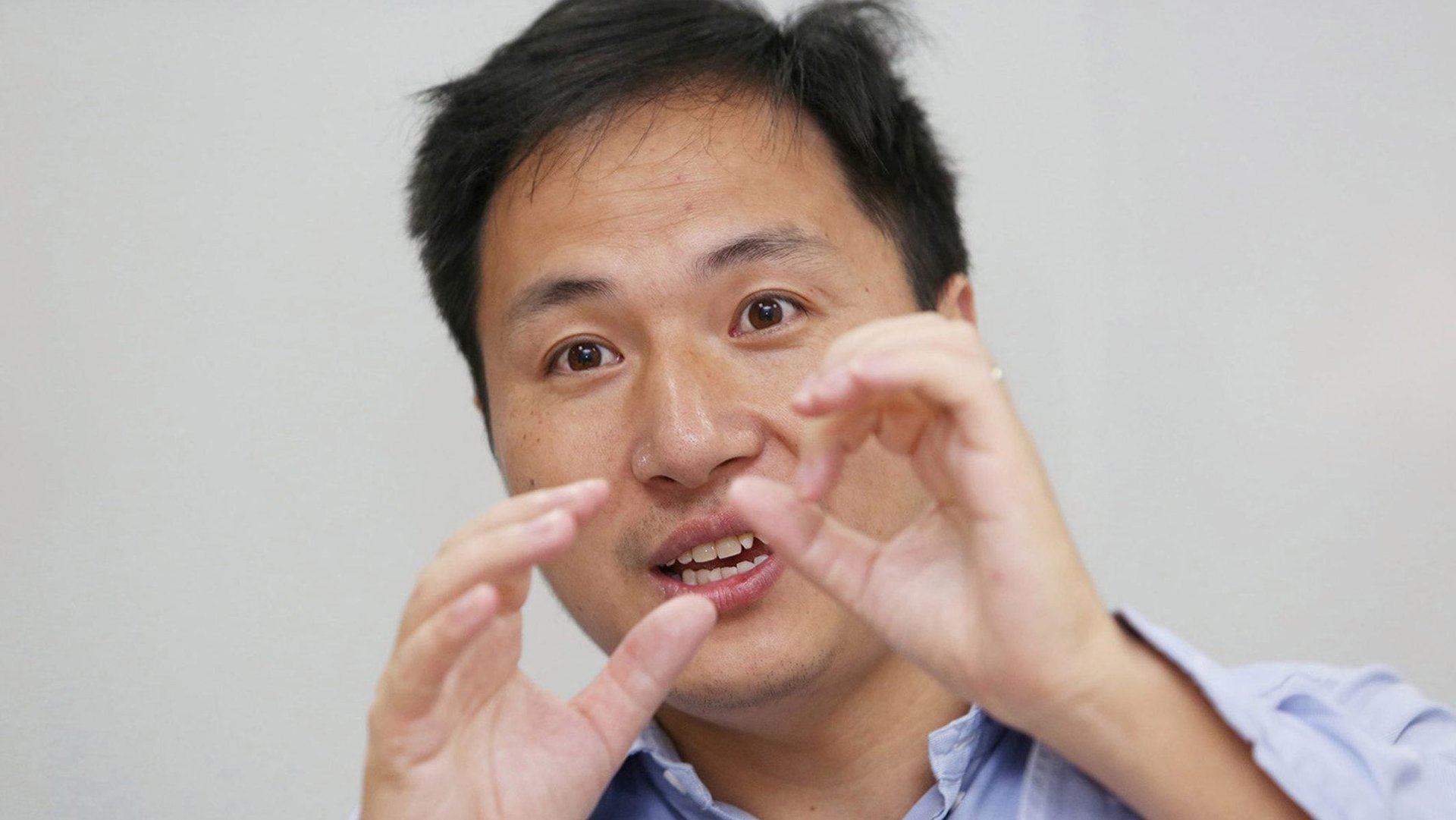

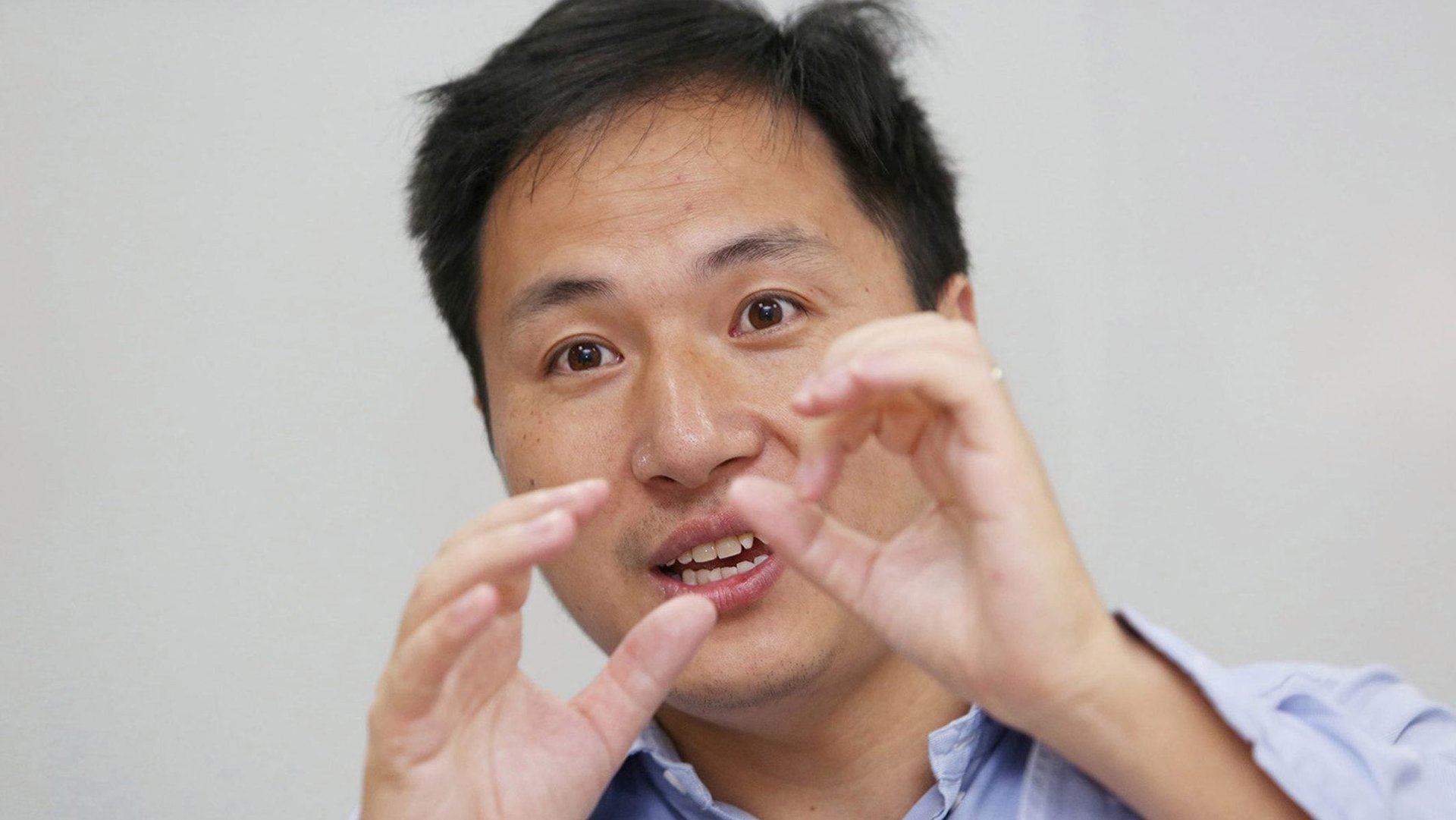

When news broke late last year that Chinese scientist He Jiankui might have created genetically-edited twins, he quickly drew the condemnation of scientists globally—and in China. And as questions swirled about how he could have got approval from the necessary government bodies, national and local research bodies disavowed knowledge of the experiment, and announced plans to investigate.

When news broke late last year that Chinese scientist He Jiankui might have created genetically-edited twins, he quickly drew the condemnation of scientists globally—and in China. And as questions swirled about how he could have got approval from the necessary government bodies, national and local research bodies disavowed knowledge of the experiment, and announced plans to investigate.

But an investigation published yesterday (Feb. 25) by the Boston-based health and medicine-focused news outlet STAT, suggests three government institutions, including the country’s science ministry, may have funded He’s research.

He claimed that he had helped bring twin girls with HIV resistance into the world by editing their genes with a tool called Crispr-Cas9, a genetic tool that can precisely target and cut a particular gene out of 20,000 human genes. At a gene conference in Hong Kong ahead of which his carefully orchestrated announcement was put out, He said his funding came partially from his own money and some from a generous startup fund provided by the university when He was first recruited. Soon after that public appearance, He appeared to be under some form of house arrest (paywall).

STAT reviewed a 14-slide Chinese-language presentation prepared by He’s team and shared with the outlet by a scientist involved in the Crispr project, as well as patient-consent forms, and information in China’s clinical trial registry. It found the documents listed China’s Ministry of Science and Technology, the local government-affiliated Shenzhen Science and Technology Innovation Commission, and He’s public university, the Southern University of Science and Technology in Shenzhen, as sources of funding.

The ministry’s “state key research program” was listed as a funding source in the slide presentation, which detailed how volunteers were recruited, while the consent forms listed He’s university, which last year said in a statement (link in Chinese) that He’s research was carried out without its knowledge. The clinical trial registry, meanwhile, showed that the Shenzhen innovation commission funded a program called the Shenzhen Science and Technology Innovation Free Exploration Project, which in turn funded He’s experiment.

STAT adds, however, that it’s not clear the institutions knew how their funding would be used, and that it’s possible that He—who appears to have been a recipient of generous research funds since his return to China in 2012 after graduate studies in the US—used funds he had obtained earlier for the Crispr project. The science ministry said in a statement to STAT citing a preliminary investigation that “it did not fund He’s activities of human genome editing.”

Local officials in southern Guangdong province, where He’s university is located, said last month after an inquiry that He had carried out and funded the research on his own, state news agency Xinhua reported.

It also remains unclear exactly where the in vitro fertilization and gene splicing was carried out, STAT said. Clinical trial documents list HarMoniCare Shenzhen Women and Children’s Hospital as having provided ethics approval, MIT Technology reported at the time of the announcement, but STAT notes the hospital doesn’t have IVF facilities.

The university didn’t respond immediately to queries sent over social media Weibo by Quartz. He and the Shenzhen commission could not be reached for comment.

Little is known about the well-being of the babies He reportedly created—although the Xinhua report says they are under medical observation. Meanwhile another such baby may be on the way, the scientist revealed during his last public appearance.

Scientists say the world is not ready for the risks of creating gene-modified people given how little is know about the cascading effects of such modifications. MIT Technology Review reported last week that the experiment might have enhanced the babies’ brains (paywall), while the Associated Press, when it broke the news of the babies’ existence, raised the concern that the altered genes could result in a higher risk for infections from other viruses such as West Nile.