One professor’s 10 rules for reading long, difficult nonfiction

Have you ever finished a nonfiction tome that took so long to read you forgot how it started? Or worse, what you were meant to have learned? Reading and retaining dense nonfiction is a skill, especially when it comes to what UC Berkeley economist Brad DeLong calls “big, difficult, flawed, incredibly insightful, genius books.”

Have you ever finished a nonfiction tome that took so long to read you forgot how it started? Or worse, what you were meant to have learned? Reading and retaining dense nonfiction is a skill, especially when it comes to what UC Berkeley economist Brad DeLong calls “big, difficult, flawed, incredibly insightful, genius books.”

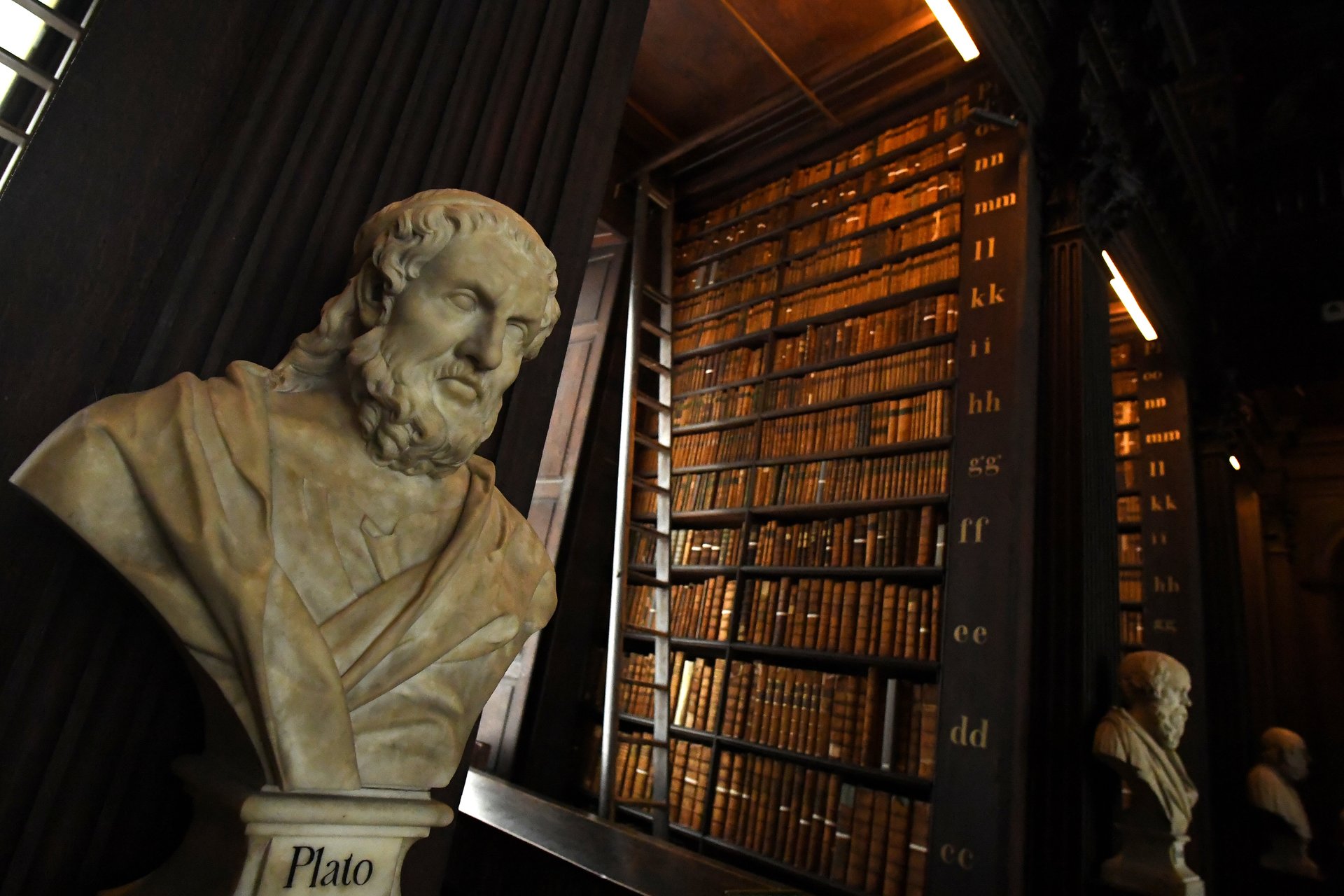

DeLong teaches a course on the history of economic thought in which students spend a semester reading just three books: Adam Smith’s The Wealth of Nations, Karl Marx’s Capital, and John Maynard Keynes’ The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money. In a blog post earlier this week, DeLong described 10 rules he gives students for how to read, retain, and learn from books like these (quoted here in full):

- Figure out beforehand what the author is trying to accomplish in the book.

- Orient yourself by becoming the kind of reader the book is directed at—the kind of person with whom the arguments would resonate.

- Read through the book actively, taking notes.

- “Steelman” the argument, reworking it so that you find it as convincing and clear as you can possibly make it. (Author’s note: “Steelmanning” refers to grappling with the strongest possible version of an argument, the opposite of attacking a “straw man.”)

- Find someone else—usually a roommate—and bore them to death by making them listen to you set out your “steelmanned” version of the argument.

- Go back over the book again, giving it a sympathetic but not credulous reading.

- Then you will be in a good position to figure out what the weak points of this strongest-possible argument version might be.

- Test the major assertions and interpretations against reality: Do they actually make sense of and in the context of the world as it truly is?

- Decide what you think of the whole.

- Then comes the task of cementing your interpretation, your reading, into your mind so that it becomes part of your intellectual panoply for the future.

The bad news is that reading like this takes more time, especially if you follow rule 6 and reread some or all of the book. But if you’re spending the time to read a 1,000 pages, it’s probably worth some extra effort. After all, the first question to follow “Did you read _____?” is usually “What did you think about it?”

But even if you’re not willing to take notes or, god forbid, reread, some of DeLong’s tips can still help you retain what you learn. Rules 4, 5, 8, and 10 all involve not just taking in the book’s argument, but restating or reinterpreting it to make it your own. This resembles the Feynman Technique, a learning strategy described by the Nobel Prize-winning physicist Richard Feynman, which involves explaining a new topic out loud or on paper in simple terms as if you were teaching it. Thinking about how you would explain the idea to someone else forces you to confront any gaps in your understanding, which is what several of DeLong’s recommendations aim to do.

Rule 1 is also good, and doesn’t take much time. Reading up briefly on the context for a book—when it was written, for whom, what was going on at the time—can make it much easier to understand and appreciate what the author is up to. That pre-reading can also help you decide if you actually want to read the book. Some lengthy, dense, influential nonfiction is worth reading in full, and in those cases DeLong’s rules can help. But I’d add my own rule to his list: Lots of influential nonfiction books are much longer than they need to be, and so you’re often better off just reading a magazine or journal article summarizing the argument.