A new UK university wants to teach students skills employers actually want

Getting a university degree has never seemed more important: college graduates earn more money, live longer, and are happier. But college degrees are expensive (especially in the US), narrowly focused (especially in the UK), and often fail to build the skills employers want (true in most countries).

Getting a university degree has never seemed more important: college graduates earn more money, live longer, and are happier. But college degrees are expensive (especially in the US), narrowly focused (especially in the UK), and often fail to build the skills employers want (true in most countries).

A new university in the UK wants to change that.

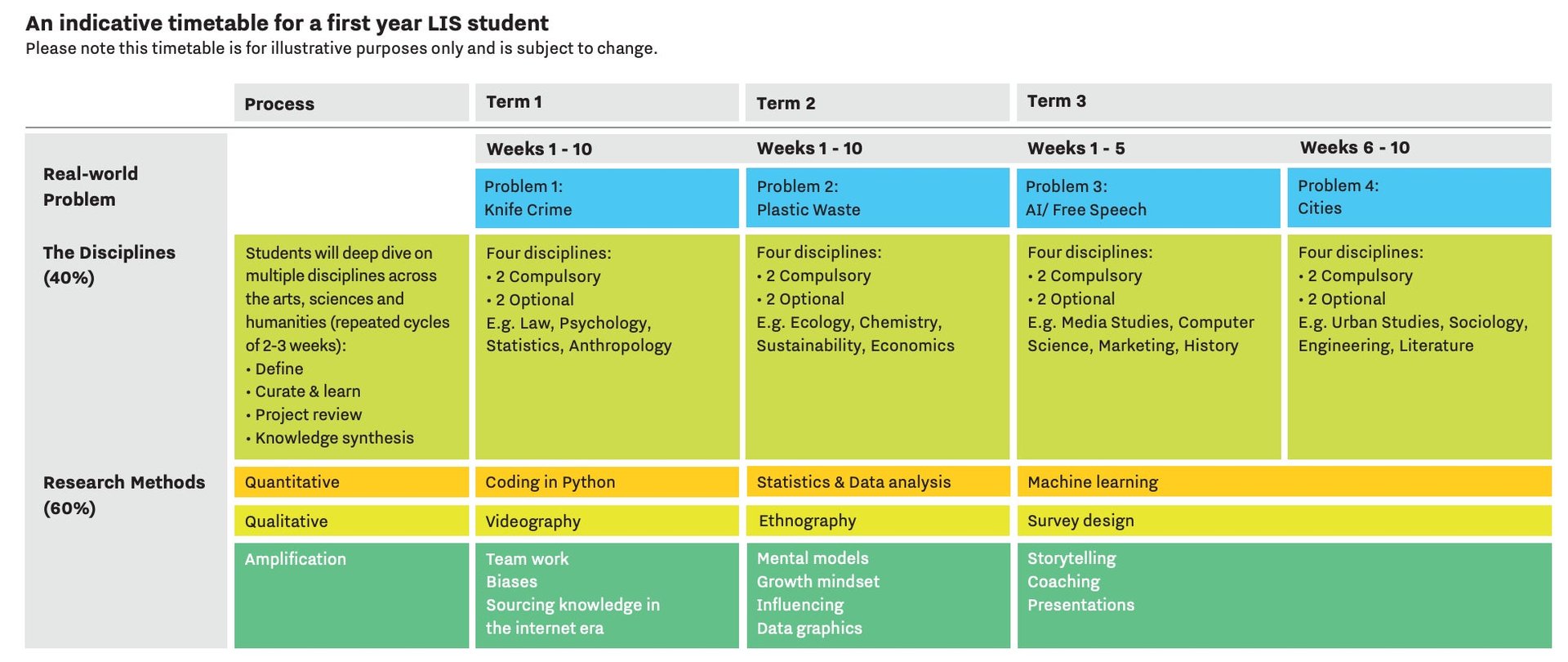

The London Interdisciplinary School (LIS), which will launch in 2021 with a target of 100 students, will scrap traditional academic subjects and offer a three-year bachelor of arts and sciences degree designed to tackle real-world issues. The curriculum is built around interdisciplinary problems—knife crime, childhood obesity, palm oil in supply chains, plastic pollution—as well as quantitative and qualitative research skills. Employers like the Met Police, Innocent, and Virgin will provide project ideas and offer five-week work experience for students.

“We’re going to try and create a really transformational educational experience where all the people in the institution are waking up every morning and saying, ‘How can we take these brilliant young people and give them an amazing learning experience?” says Ed Fidoe, a co-founder. “That’s not happening in many universities.”

The idea is similar to a US liberal arts degree (a rarity in the UK) but also more explicitly focused on “interdisciplinarity,” or drawing on multiple subjects—economics, psychology, sociology, statistics—to solve complex problems like childhood obesity. In other words, the problem, not the subject, sits at the center of the curriculum. The skills students develop, the founders hope, will more closely align with what an AI-infused, automated world demands: collaboration between people and machines, critical thinking, speaking and writing skills, and data management, to name just a few things.

Fidoe says the motivation for founding a university was threefold: change an admissions process that distorts education and narrows it unnecessarily; build a better learning experience for students; and align the interests of students with the faculty teaching them. Fidoe is scathing in just how mismatched this alignment is in the current system: universities, he says, are geared toward research, not students.

“We’re taking 400,000 people every year and putting them in UK universities and saying you need to spend three years in university taught by people who are motivated to do something else,” he says. “That’s kind of mad.”

Fidoe left McKinsey in 2010 to start School 21, a K-12 state-funded school built to educate disadvantaged students holistically, in a country which currently tilts disproportionately toward academics (kids take a raft of GCSEs, or subject-level tests, at 16 and then another set of high-stakes exams at 17). School 21 focuses on academics as well as communication and problem-solving. It’s become an international darling: every year, 1,500 educators pay to visit and study its approach.

But Fidoe saw that the skills School 21 builds were not valued in the university admissions process, making them a hard sell to parents and students. Collaboration and good debate skills may be needed in the workplace, but good test results get you into university.

“Every 17-year-old has to say, ‘All my life have I ever wanted to study chemistry’,” says Fidoe. “It’s just a lie.”

The challenges of building a new university from scratch are daunting: students have to sign up for, and pay for, something untested; faculty have to teach in a totally new and different way; London real estate is expensive; and there’s a risk that an interdisciplinary curriculum will be superficial (interesting, but thin). Fidoe admits it’s a tall order. “Are any 17-year-olds going to be nuts enough to come to something that doesn’t exist yet versus something that’s been around 150 years?” he says, when questioned about the hardest part of building a university from scratch.

Even more challenging, perhaps, is that the university has to be approved by a new regulator, the Office for Students, using an outdated rulebook. The 1997 Dearing Report was the last significant attempt to define the goals of education, says Carl Gombrich, academic lead at LIS, suggesting the goals have changed.

LIS was meant to launch in 2020, but did not secure regulatory approval in time, which it needs to for students to take out loans. In January, LIS informed the nearly 300 students who had applied that they could defer for a year, or cancel the application and start over. Fidoe says the hold-up was a combination of a new regulator with a massive backlog of approvals, and the fact that it had to approve a university that was still being built as they sought the go-ahead. It’s like building a plane when it’s in the air, Fidoe says.

What an LIS degree will look like

This is not Gombrich’s first attempt to build something new. In 2012, he launched University College London’s Bachelors of Arts and Sciences (BASc) degree, “in order to deliver a truly interdisciplinary education at a world class institution.” It’s been a success: it has a high retention rate in the joint faculty at UCL (97%), students do well in post-grad employment, a high proportion go onto “elite” post-grad programs, and students like it. “The Arts and Sciences course at UCL was twice recognized by the Provost as performing in the top 10% of courses for student satisfaction,” Gombrich says.

BASc students have outperformed single-subject students in some disciplines. Two BASc graduates received the top award in organic chemistry—one while also studying Arabic and management accounting; the other anthropology, business, and coding.

“It’s academics who think you need 24 modules in one discipline to be a proper graduate,” says Gombrich. “Kids are like, ‘not so much, I will take what I need but complement it and enrich it’.“

Admissions at LIS are labor intensive. In the UK, students apply through a central clearinghouse, and exam results are paramount. At LIS, students will instead apply directly and all will be invited to a “selection day” which will include a face-to-face interview so that LIS can understand a student’s background, motivations, and passions. Interviews will be conducted by a panel to minimize bias. Conditional offers will be granted based on personal background, circumstances and, also, grades.

This is meant to help disadvantaged students, a key target demographic. According to Gombrich, these students “tend to see the way to to be aspirational, really, is to do medicine, law, engineering.” The kind of degree LIS will offer would likely be considered a luxury, but “one of my personal missions is to show that that’s completely false,” he says. “Actually, this will lead to probably more more pay, more exciting and more fulfilling jobs than those traditional disciplines.”

The degree is very structured, especially at the start, perhaps in an attempt to assuage fears that it’s too student-led, or too passion-driven. Gombrich says the goal is to eventually give students ownership over the problems they are solving, but not before they have built the skills to do so. “There is something about wisdom and knowing what’s really going on in the wider world, which is very hard to do when you’re 18, 19,” he says.

The degree will have 9-10 faculty, moving to 20-30 in year three. More than 600 faculty applied for six posts.

Students will draw on threshold concepts, pioneered by Ray Land at Durham University. These focus on the idea that every discipline has fundamental concepts which act as gateways to understanding the discipline. And students will tackle problems through various disciplines: knife crime, for example, by understanding cultural and socioeconomic factors in different neighborhoods, data science, statistics, publicly available data, an economics or psychology lens, and trying to understand the honor between groups and communities.

Will it work?

Building a university is not for the faint of heart. Fidoe asked his team to come up with an analogy for the task they face. They suggested:

- David vs Goliath, with catapults banned

- Building a bullet train on old tracks

- Scaling the electric car when they’re subsidizing petrol

- Preparing a kosher, halal, vegan Christmas dinner to satisfy meat-only diet aficionados

- Making sense of a life while you’re living it

The challenge is more the bureaucracy than the public, they argue. “How disruptive can we be and still be a university in the eyes of the public is a really interesting question,” says Gombrich. The past year convinced them that parents and students were ready for a radical new approach.

While reforms that created the Office for Students were intended to foster innovation, education has never been a sector that eagerly embraces change. “There’s definitely room for new providers who want to provide education in different ways,” Nick Hillman, head of the Higher Education Policy Institute, a think-tank, told the Financial Times. “But everybody who has tried to get a new higher education institution off the ground has found it much tougher than they thought, in obtaining the right data, getting student loans and ticking the regulatory boxes.”

Many worry about the tension between depth and breadth. “If you end up knowing lots of things lightly and nothing deeply, there’s a finite number of things you can end up doing, like mid-management,” says Vineet Bewtra, an education advisor who has also worked in venture capital.

Alex Beard, senior director of Teach For All and author of Natural Born Learners, agrees rigor is a concern but says the hires LIS has made “pitch it firmly in the academic and rigorous, yet progressive and new space, which means it’s got a great chance of succeeding with students and policymakers alike.” He points to Gombrich and Daisy Christodoulou, an adviser, whose work in secondary education has consistently focused on the critical importance of knowledge amidst a fervor to shift education to more 21st-century skills. “LIS had a much more nuanced understanding of what is meant by 21st-century skills,” she says, including the role of pedagogy (how things are taught), how we learn, and what we need to learn.

She joined the project because of the scale of its ambition, the blank slate to do things better, and the chance to put teaching squarely at the center of the student experience. “The role of teaching undergraduates doesn’t get the attention it deserves,” she says. She is also eager to experiment with new innovations in marking, or grading. She’s the director of education at No More Marking, a comparative judgement engine that uses data and statistics to assess open-ended tasks, including writing (with better accuracy and transparency than humans). She was an English literature major and now works with data and statistics, arguing that LIS will prepare students for exactly this kind of combination of arts and sciences: “That’s the way the world is going.”

The big picture

LIS is not alone in trying to tweak, reform, or upend higher education. Beyond MOOCs (massive open online courses), which have not yet delivered on the idea of democratizing access to higher education, new models of higher ed are cropping up around the world, both starting from new and also working within the system as it is. Results have been mixed.

Ben Nelson, former CEO of Snapfish, founded Minerva in 2014 to be “the first elite American university to be launched in a century.” (Its mission: “Nurturing Critical Wisdom for the Sake of the World.”) Students study in seven countries over three years, using interactive online video courses. Last year, 23,700 students applied, 273 qualified for entry and 183 enrolled, making admissions way more competitive than Harvard’s.

Many universities, including Oxford and Cambridge, are experimenting with ways to improve access, including funding a transition year for students from more disadvantaged backgrounds. In January, David Roux, a co-founder of private equity firm Silver Lake Partners, donated $100 million to Northeastern University to establish a graduate school and research center in Portland, Maine with an eye toward life sciences. The idea was to both build talent and reinvigorate a community.

Minerva has made it clear that it’s aimed at the elite. Bewtra, the investor and advisor, says focusing on the middle tier of students could be helpful for LIS. “I suspect they may get most traction if they aim for students who would be most failed by below-average universities, where a lot of time and cost can be demanded of learners and it’s debatable what the students get at the end with employability.” He is clear that if they do this, they need to make sure that employers are on their side. “Universities are all about signaling—they have to make their signal worth something,” he says.

Christodoulou is clear LIS is not for everyone. “There’s never been a university in history where you would say it’s right for 100% of the population,” she says. Still, it fills a gap. And the closer ties to business mean that the curriculum will be informed by what students need. “It’s a reminder, constantly, of the world students are going to graduate into,” she says. With automation coming for our jobs, that reminder is a timely one.