Regulators are watching the new entities collecting America’s mortgage payments

The new non-banks playing an outsized role in the US mortgage business are increasingly drawing scrutiny from US government regulators.

The new non-banks playing an outsized role in the US mortgage business are increasingly drawing scrutiny from US government regulators.

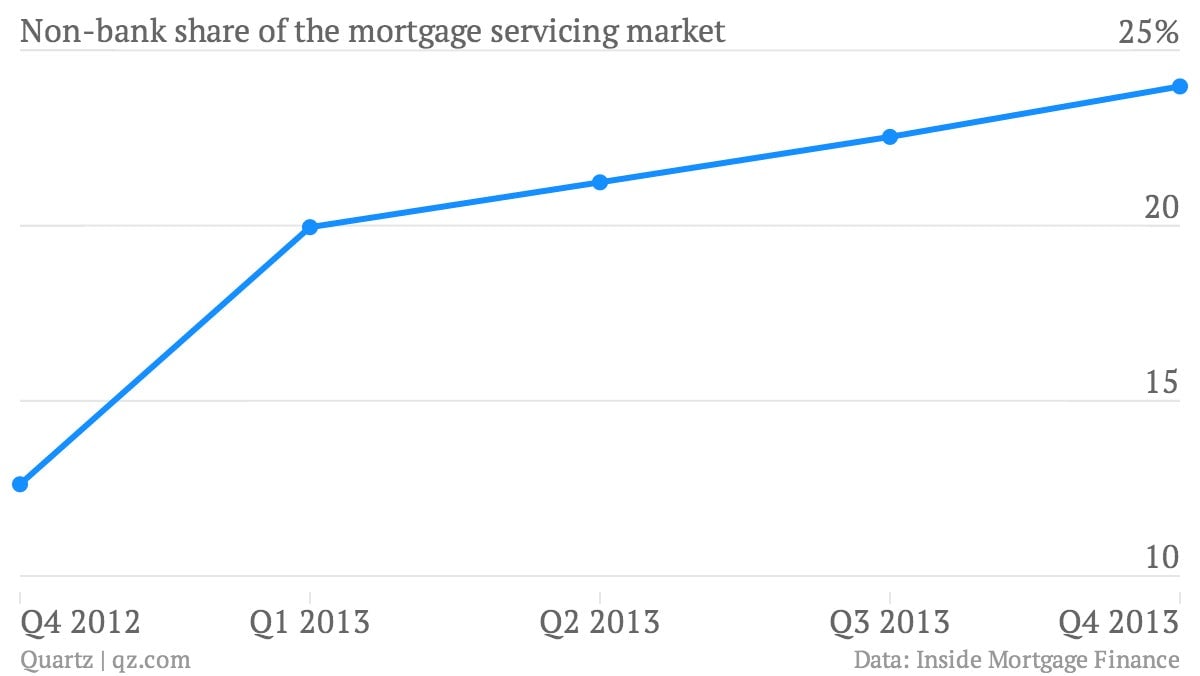

Indeed, the New York Times reports today that a crop of non-banks are creating headaches for some troubled American homeowners, as those homeowners seek to modify their mortgages in order to stay in their homes. As reported by Quartz, a wave of so-called non-banks, including Ocwen Financial and Nationstar, are capturing a greater share of the US mortgage servicing business.

It’s a business that banks like Wells Fargo (paywall), Bank of America and Citigroup have been retreating from after incurring tens of billions in penalties for improperly foreclosing on homeowners. The nation’s biggest mortgage lenders (who traditionally have been the biggest mortgage servicers) inked a sweeping multi-state $25 billion national mortgage pact in order to settle charges that they mishandled mortgage paperwork.

The New York Times now reports that non-bank mortgage servicers, Ocwen and Nationstar—who have bought up more and more of the rights to handle US mortgage payments recently—are approving far fewer home modifications than their bank counterparts:

Katherine Porter, who was appointed by the California attorney general to oversee the national mortgage settlement, says complaints about mortgage transfers have surged, adding that the servicing companies have “overpromised and underdelivered.” Her office alone has received more than 300 complaints about servicing companies in the last year.

These non-banks have been attracted to the mortgage servicing market because of the steady stream of income such rights provide. Mortgage servicers collect a fee, (anywhere from 0.25% to 0.50% of the principal of the loan) to ensure that payments from homeowners are distributed to investors in the complex mortgage bonds where nearly all US home loans eventually end up.

In other words, mortgage servicers collect payments from millions of American homeowners each month. And that means these companies are often the first point of contact if there is trouble with a borrowers’ ability to make payments. But regulators are concerned that these companies don’t have much incentive to help homeowners figure out a way to stay in their homes.

For example, if a mortgage is modified by lowering the principal outstanding, that would also lower the fees that a mortgage servicer collects. (Remember, the fees are a sliver of the principal of the loan.) New York state’s top financial regulator, Benjamin Lawsky, voiced such concerns about non-bank servicers earlier this month. For their part, Ocwen and Nationstar defended themselves in the New York Times piece today:

The servicing companies defend their track records, saying they have had success in keeping borrowers in their homes. Ocwen pointed to its investment in customer service, while Nationstar emphasized that it assisted 108,000 homeowners with some form of modification or other repayment plan in 2013.