China’s coronavirus outbreak is unfolding in a new age of information—and surveillance

When the SARS outbreak hit China in 2003, only 6% of the population had access to the internet. Seventeen years later, that number has increased tenfold: more than 61% of the Chinese population are now online, according to the latest government figures.

When the SARS outbreak hit China in 2003, only 6% of the population had access to the internet. Seventeen years later, that number has increased tenfold: more than 61% of the Chinese population are now online, according to the latest government figures.

The daily lives of Chinese citizens today are shaped, to a large extent, by something that didn’t even exist in 2003: WeChat. Launched in 2011, the all-encompassing app is, for many in China, the internet itself. It’s where citizens read, chat, shop, socialize, and pay for everything from taxi rides to groceries. It’s also a platform where the state surveils its people.

This is the backdrop against which China’s coronavirus outbreak, which has sickened some 2,000 people (link in Chinese) and killed nearly 60, is unfolding in 2020: hyper-connectivity and the rapid dissemination of information—and at the same time, heightened state surveillance. All of this affects how news of the current disease outbreak is shared and censored.

This year, as in the SARS era, Chinese officials appeared to downplay the seriousness of a deadly spreading virus until the facts became impossible to ignore. Chinese health authorities went in the space of a week from saying the outbreak was “preventable and under control“ to freezing travel from more than a dozen cities—an unprecedented measure—and one that undoubtedly raised concerns that the situation was more serious than officials had earlier been letting on.

“I can see the same pattern,” said Rose Luqiu, an assistant journalism professor at Hong Kong Baptist University who covered SARS in 2003, when asked if she saw similarities in how the government handled the flow of information during the two outbreaks.

Containing the spread of virus news on WeChat

In the SARS crisis, despite the first case being discovered in November 2002, a “virtual news blackout” prevailed around the outbreak for months; when it did become public, the country admitted to having just a few cases. It wasn’t until a feisty newspaper (whose staff were later detained for their continued dogged reporting) broke the news and a whistleblower came forward that officials publicly acknowledged the extent of the SARS outbreak. At the time, microblog platform Weibo and messaging app WeChat were still years away, people could bypass the government and share news mainly by text message.

Now, the sheer amount of information shared every minute by internet users in China today means that it’s impossible for the state to maintain a watertight seal on what’s posted online.

“The dynamics of WeChat groups in particular shape the discussion of this epidemic,” said Hongmei Li, an associate professor of strategic communication at Miami University. “WeChat groups are characterized by a mixture of official and nonofficial information, foreign and domestic news, and personal observations and experiences. This suggests that it is difficult for the Chinese government to control news.”

Online, there has been a steady trickle of photos, videos, and witness accounts from overwhelmed hospitals that seem to undermine the state’s narrative of having the situation firmly under control. Along with reports from medical personnel, some of these grassroots accounts may have played a role in authorities moving to build temporary hospitals in Wuhan. While some hashtags and posts are quickly scrubbed by censors, others—like the hashtag #Wuhan on lockdown#—are allowed to remain, showing the government’s attempts to walk a delicate line between censorship and transparency.

“With the two social media platforms, the worry now is not about not getting enough information, but is more about how to distinguish which piece of information is true,” said Wilfred Wang, a lecturer in media at the University of Melbourne who researches Chinese social media. “The way Beijing deals with the explosive amount of information is to adopt a ‘one eye open one eye closed’ attitude toward criticisms that do not advocate collective actions or attack the central government directly.”

Unusually, state-run papers like People’s Daily posted about a shortage of face masks in Wuhan, which had mandated the use of the face coverings, while in an English-language report the state-run tabloid Global Times described a shortage of testing kits. The People’s Daily post about the face mask was later deleted, the Washington Post reported.

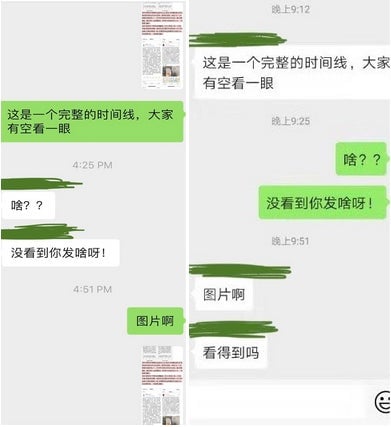

The desire to limit information critical of Beijing can sweep up even general information shared between individuals—including outside China. Earlier this month, a timeline of developments in the coronavirus outbreak was being widely shared on WeChat but then began to be censored, according to users Quartz spoke to. Quartz on Jan. 22 tried and failed to send the image via a private chat between a user in the US and one in the UK. There was no notification to the sender that the picture had not been sent, which often happens when people try to send “sensitive” content on the app. However, the person in the UK never received the picture on her end. After rotating the photo, it went through.

The same day, social media platform Weibo blocked the posting of a photo of a front page of the People’s Daily on Jan. 23, which had drawn attention for being devoted to coverage of Xi Jinping, and none of the virus. The image was blocked even though it was not accompanied by any additional commentary of the sort users shared on Twitter.

These acts of censorship chip away at the public’s trust in the authorities—at the exact time when the state most needs it in dealing with a public health crisis. As one article in medical journal The Lancet put it, “It is impossible to build trust while at the same time abusing it.”

Supercharged surveillance

While Chinese citizens are more connected than ever before, they are aware that state’s capacity for surveillance is also unprecedented.

“Over the last 10 years, the government has developed a very sophisticated capacity to control information,” said Luqiu, the journalism professor. She pointed to cybersecurity rules which took effect in 2017, as a powerful tool of control that the government did not have in their arsenal in 2003. The law tightened China’s censorship regime, criminalizing any online posts that the Communist party deems damaging to “national honor,” “disturbing economic or social order” or contributing to the “overthrow of the socialist system.”

The effort to control the online discussion began as soon, or even before, the first pneumonia cases been made public, when police in Wuhan said on Jan. 1 they had arrested eight local people (link in Chinese) for “spreading rumors about pneumonia”—without any clarity about the kind of information they were sharing. The Wuhan government, in its announcement, urged people “not to create rumors, believe rumors, or spread rumors, and to build a harmonious and clear cyberspace.”

Zhang Xinnian, a Chinese lawyer, critiqued the local government move in a post that was viewed more than five million times before it got deleted. “The government now thinks citizens who exchange information that they cannot necessarily verify are the same as those who intentionally spread rumors, this view is very chilling,” he wrote, noting that the incident underscored the weakness inherent in China’s political system.

Aware of the surveillance, Chinese people have developed coded ways to speak about taboo topics. On one of the more liberal corners of China’s internet, some users vented their anger at the authorities on the review page for the TV show Chernobyl—and also shared show references on other social media platforms to compare China’s attitude to that of the Communist Soviet Union when the nuclear disaster unfolded in 1986. Access to that page is now restricted to registered users.

Still, China seems to have gotten more media savvy over the years, too. In 2003, Zhong Nanshan, the epidemiologist helped expose the scale of the SARS outbreak, didn’t give his first interview until April (link in Chinese)—months after the first case of SARS was discovered in November 2002. This time, however, he spoke with state broadcaster CCTV within three weeks of of the Wuhan government reporting a cluster of pneumonia cases to the World Health Organization. Allowing such a central figure as Zhong to take an interview, said Luqiu, is a strategic way for the government to both “raise awareness and lower panic.”

Some health experts and officials—including Germany’s health minister—note that China has been far more transparent this time than in 2003. On WeChat, there is even a whistleblower feature for users to notify the government of officials’ negligence and malpractice during the outbreak—though the state’s reputation of persecuting whistleblowers could make many users wary of making a report.

Still, the public in China may also be less critical of the government than observers outside China may think, given the inherently fluid nature of a virus outbreak and worries about misinformation among a citizenry that has become more nationalistic over the years.

In recent days, as the death toll climbed, China’s actions to contain the virus have intensified, as have communications from officials regarding the seriousness of the situation. China’s National Health Commission deputy director Li Bin vowed last week that the government would “disclose information on the outbreak based on facts” in a timely manner. On Saturday (Jan. 26), Chinese leader Xi Jinping said the outbreak was of “grave concern” and ordered a centralized response to tackle the epidemic.

And Chinese citizens in various provinces have set up a volunteer-run crowdsourced information and fact-checking portal (link in Chinese) to share updates and debunk false claims. The site ends with a quote from Lu Xun, arguably the most famous Chinese writer of the modern era: “If there is no torch after all, then you are the only light.”

The age of connectivity has certainly empowered Chinese citizens to shine some light into an opaque system, making it much harder for the state to impose the kind of information blackout that prevailed during SARS. Whether the government will embrace the need for extreme transparency, or eventually snuff out even that little bit of light, is another question.

Tony Lin and Tripti Lahiri contributed reporting.