On Friday (Jan. 24), the Chinese government took the dramatic step to expand its travel ban to prevent the spread of a novel coronavirus that likely originated in a live animal market in the city of Wuhan. The quarantine now encompasses 12 cities, impacting 35 million residents, thought to be the largest-ever intervention of its kind.

Even with that unprecedented action, it’s likely too late for the quarantine to have its intended effect, experts contend. “Three weeks ago they should have started screening people coming in and out of Wuhan,” says Nischay Mishra, a virologist a the Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health. “They could have contained it.”

But once a quarantine area expands to whole cities, it is much less effective, says Leila Barraza, an assistant professor of public health at the University of Arizona.

In past outbreaks like swine flu and HIV, banning travel to or from an area with a high density of infections has often not reduced the number of people infected. Instead, quarantines can serve to hinder aid, resources, and supplies to the most affected areas—a consideration that likely delayed the decision to implement initial travel ban on 20 million people in Wuhan and four surrounding cities, announced on Jan. 23.

“If it’s a decision to quarantine millions of people, you have to consider if there is food to supply all those people, if there are healthcare resources, things like that,” Barazza says. “Trying to reopen everything [after a quarantine] can take a while.” Without a picture of resources within the quarantined area, the impact of the expanded quarantine on residents is unclear. “In most cases, though,” Barazza says, “there must be a lot of preparation for healthy and non-healthy individuals if they must stay within a certain area.”

Despite the benefit of hindsight, it’s not clear that implementing a travel ban earlier would have been better. Leaders are in a difficult position, Barraza says, because they are trying to protect people without understanding all the information about the disease. In the early stages of an outbreak, lab technicians and epidemiologists work to understand the disease, while public health officials and other government employees must figure out how to contain the infectious agent.

They’re also trying to minimize damage to the public’s trust. “If you’re screening people, shutting everything down, closing schools, and taking extreme measures, but then nothing happens, the next time around people aren’t as trusting and as willing to comply,” says Barraza. And every day of a quarantine is a huge suck on an area’s economic activity.

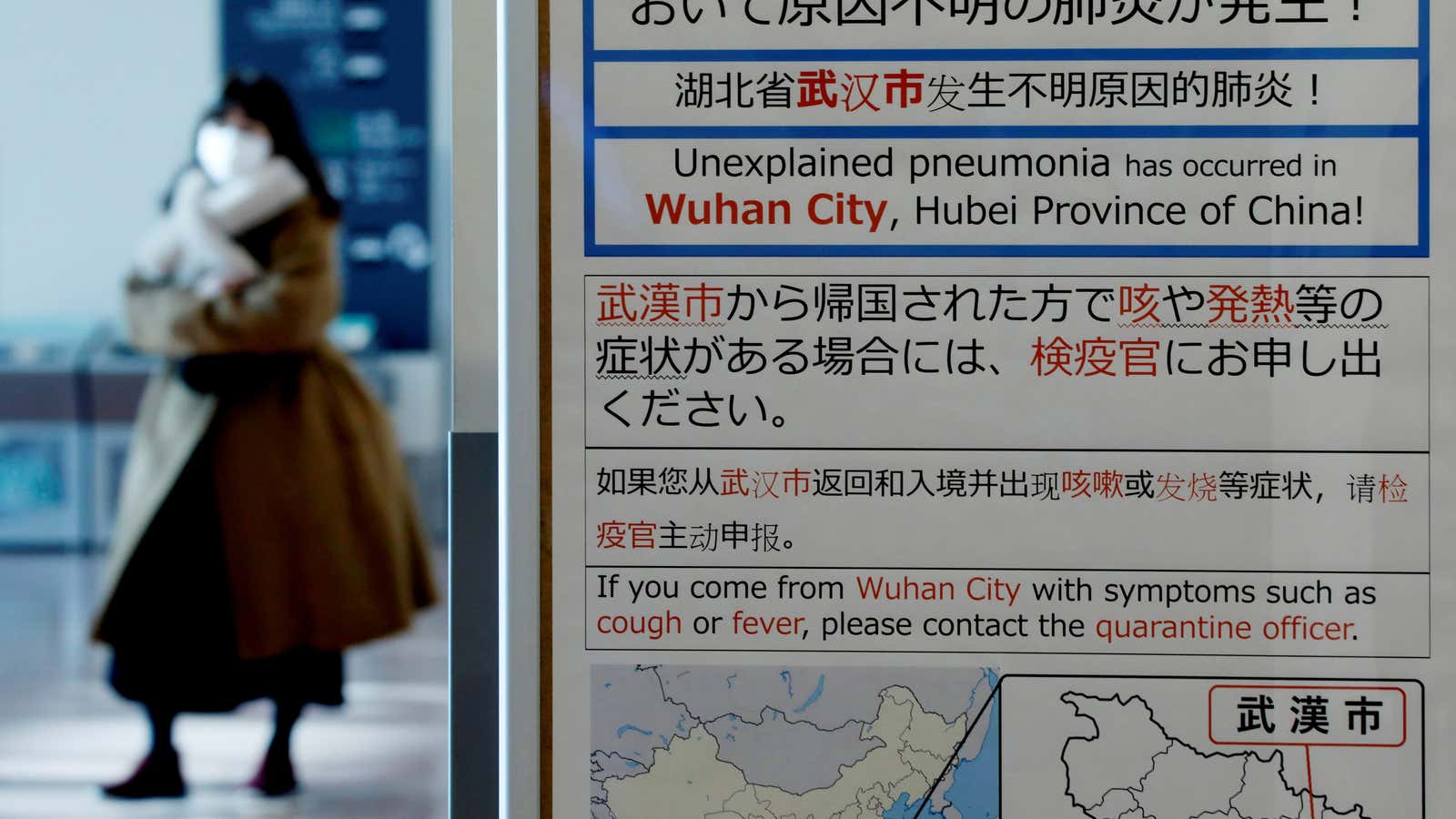

Whether or not the travel ban succeeds in limiting the spread of the virus, local governments can pull several other levers. Airport screening, experts agree, can be a good precautionary measure—although they generally don’t do much to identify people with the disease, nor prevent its spread. Governments can also limit people’s contact with one another, as the Chinese government has done by shutting down Wuhan’s public transportation system, markets, and large-scale social events planned in celebration of the Lunar New Year.

But the success of each of those interventions depends on how the new coronavirus is spread and the severity of its symptoms. Which is why the most effective tool at a government’s disposal is sharing information with its citizens (pdf). Clear, top-down, frequently updated information about an outbreak that details things like how many people it’s affected, how it’s likely spread, and what people can do to protect themselves can cut down on misinformation and panic.

In past outbreaks, the Chinese government hasn’t shared enough information with its citizens to prevent widespread panic. This one, though better than in the past, also threatens to tip into a frenzy, largely driven by WeChat.

Whether the actions the Chinese and other governments are taking now will be enough to contain the virus is anyone’s guess. As of Friday, about 900 people had been diagnosed with the virus (two in the US), and 26 people had died.

“If I was an official [in Wuhan], I would be educating people on what’s happening, encouraging people to talk to their healthcare providers, to stay home if sick, and do what we’ve done really well in public health, which is contact tracing [working backwards to identify who infected people might have come into contact with],” Barraza says.