How the Super Bowl became an unrivaled US cultural phenomenon

We tend to take the Super Bowl for granted.

We tend to take the Super Bowl for granted.

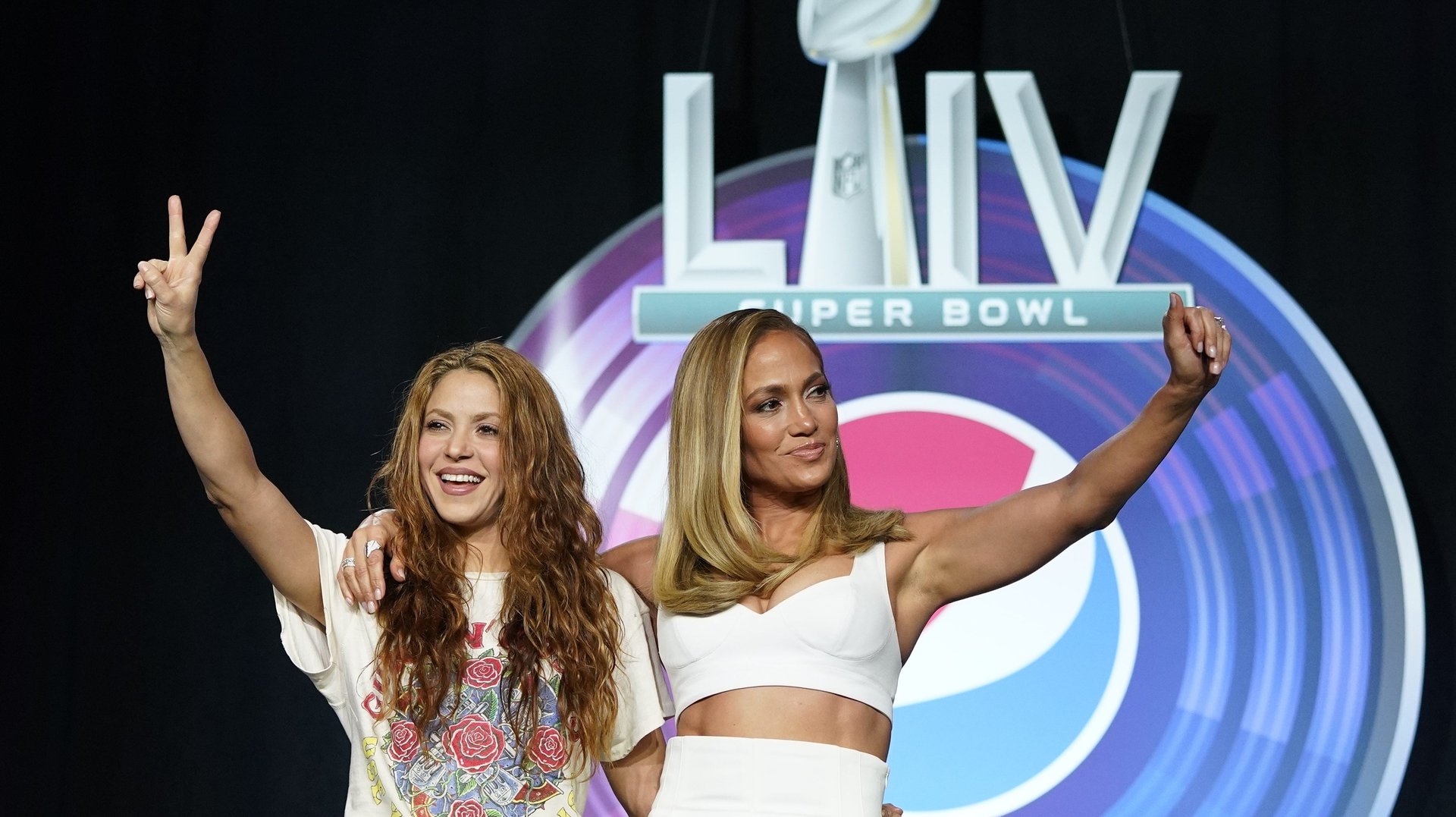

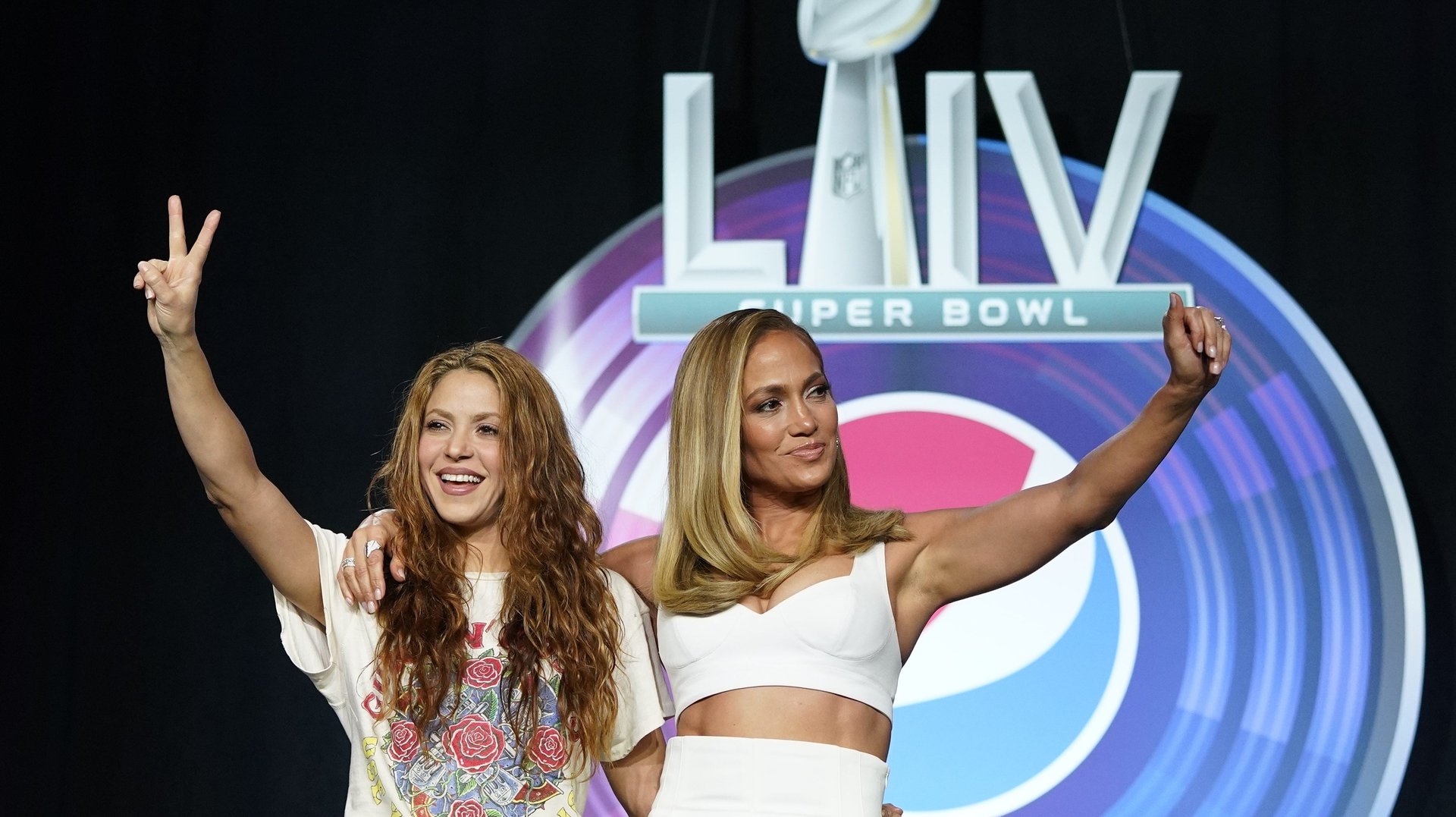

The championship game of the National Football League is the biggest entertainment event in the United States each year. It is watched by more Americans on television than anything else, by a large margin. Advertisers spend huge chunks of their annual budgets to broadcast just a few seconds of commercials during the game. Some of the world’s most popular musicians take the stage at halftime to perform the most elaborate sets of their careers. There are calls to make the day after Super Bowl Sunday a national holiday.

The whole thing is a monstrous, quasi-religious spectacle. And it’s been like that for decades.

Last year’s game was seen live by almost 100 million Americans. That actually marked a slight dip from the heights of 2015, when the game was watched on TV by 114 million people—the biggest audience for a single-network broadcast in the country’s history. (The Apollo 11 moon landing in 1969 brought in more viewers, but it was simultaneously aired across several networks.)

The 2018 telecast was watched by about 70% of US homes with TVs, up from 61% a decade ago, according to Nielsen. In fact, the Super Bowl has never fallen below that 61% share. Every year since the game started, without exception, well over half of Americans households with a TV tuned in. In many cases, more than three-quarters tuned in. (1976 marked a record 78% share.)

But how, exactly, did the Super Bowl get this way? How did it become such an unavoidable phenomenon?

It coincided with the growth of TV

In 1955, just half of American households had a TV set. In the following years, as color TV programming became more popular, the vast majority of households in the country had access to a television.

By 1967, the year of the first Super Bowl, 93% of US households had a TV (55 million total). Today, while the number of total American households has dramatically increased (about 128 million as of 2019), the percentage of them with a TV hasn’t gone much higher than that 93%. TV isn’t any more popular today relative to the population than it was in 1967—but there are a lot more TVs.

The NFL capitalized on this organic growth by getting in at the right time. American audience were hungry for big spectacles to watch communally, and football gave it to them.

It began with a built-in rivalry

As part of the merger between the NFL and its rival, the American Football League (AFL), the two leagues agreed to compete in a joint championship game in 1967, before officially merging into a single entity three years later.

The first two Super Bowls were not particularly close, as the NFL’s Green Bay Packers (led by Hall of Fame coach Vince Lombardi) defeated the AFL’s Kansas City Chiefs and the Oakland Raiders in 1967, and 1968, respectively. Those games had many wondering if the AFL teams could ever compete with the NFL, which had been around for 40 years longer.

But then came the AFL’s Joe Namath and the New York Jets, who shockingly upset the Baltimore Colts in Super Bowl III to give the AFL its first-ever Super Bowl victory. The Chiefs defeated the NFL’s Minnesota Vikings the following year, proving AFL teams could compete with the legacy NFL teams moving forward.

Synonymous with “patriotism”

Almost immediately after the Super Bowl started, the NFL wrapped itself in the American flag and initiated a close relationship with the US military, hoping to turn the spectacle into something of a holiday. It succeeded.

Pete Rozelle, a World War II veteran and the league’s commissioner at the time, organized the first military flyover during the 1968 Super Bowl. A year later, the theme of the halftime show was “America Thanks.” In 1970, the halftime show featured a reenactment of the 1815 Battle of New Orleans between US and British troops.

Since then, the NFL has marketed itself—and the Super Bowl specifically—as a uniquely American event. It has become not only a celebration of the sport, but also a celebration of the country, reflecting how many Americans (and much of the rest of the world) has now come to see it: with big, bombastic pageantry.

It helps that the game itself is incredibly violent. You don’t have to squint hard to see how it might remind viewers of war. Even some of the sport’s terminology—”trenches,” “blitz,” “bomb”—is borrowed from the language of warfare.

“From a distance, a football game resembles a pre-modern battle: two groups of men in uniforms, wearing protective gear, crash into each other,” Michael Mandelbaum wrote in The American Interest. “Like most military battles, football is a contest for territory, with each team trying to advance the ball to the opposing side’s goal.”

Teams from major media markets dominated

In the 1970s, two teams from major US markets started to dominate: the Dallas Cowboys and Miami Dolphins (in addition to the Pittsburgh Steelers, from a smaller market). In 1978, sportscaster John Facenda dubbed the Cowboys “America’s Team” because they were so good and appeared on TV so often. The nickname has stuck for 40 years.

The Cowboys, Dolphins, and Steelers combined to win seven of the 10 Super Bowls that decade. The NFL also leaned into the growing celebrity of its best players, including Namath, Terry Bradshaw, Walter Payton, and O.J. Simpson.

The 1980s marked the rise of even more big-market teams, like the New York Giants, Chicago Bears, Washington Redskins, and San Francisco 49ers—all of which won at least one Super Bowl during the decade. When the country’s most populous cities field the best teams, the league prospers.

Advertisers saw an opportunity

With access to a gigantic TV audience they couldn’t find anywhere else, advertisers realized the Super Bowl presented a unique opportunity to sell their products and brands. As the commercials became more ubiquitous, so too did the Super Bowl, feeding off each other in a tornado of corporatism.

The Super Bowl commercial that really kicked this all off was the 1973 Noxcema ad featuring Namath and actress Farrah Fawcett. “I’m so excited, I’m going to get creamed,” says Joe Namath, before Fawcett rubs shaving cream all over his face.

Intentionally raunchy, the ad was designed by Madison Avenue specifically to ignite discussion during the game and the next morning. It helped launch a wave of celebrity-endorsed products that continues to this day, and began a Super Bowl tradition of companies broadcasting provocative conversation starters to drive consumers toward their brands.

In 1978, the NFL moved the Super Bowl to primetime in the US eastern time zone for the first time, in part to please the growing number of advertisers seeking the valuable ad space. The result was the most-watched Super Bowl broadcast to date, jumping 27% in total viewers from the year prior—by far the largest year-to-year increase in the game’s history. That was perhaps the year the Super Bowl went from an already enormous event into a permanent staple of American culture.

Super Bowl ads may have reached a creative apex in 1984, when Apple introduced the Macintosh computer to the world. Directed by Ridley Scott, the high-concept Apple ad became a phenomenon, still considered today to be one of the greatest commercials of all time.

Points put butts in seats

After scoring in the NFL decreased throughout the 1960s and much of the 1970s, teams steadily began to score more points per game in the late 1970s. Other than a brief defensive blip in the early 1990s, the league has mostly maintained that trajectory to the present day. In 2019, teams averaged 22.8 points per game, up from a low point of 17.2 per game in 1977. Five of the 10 highest-scoring Super Bowls ever have all come since 2003.

Defense might win championships, but points get people to watch. The NFL prefers to keep it that way.

Unlike most other league championships, the Super Bowl is a single event. It’s easy. It’s straightforward. It’s not drawn out over several games, some of which are more exciting than others. Viewers only have to make plans for a few hours on one Sunday each winter—a time when they may not be doing much else. The Super Bowl might not be an official American holiday, but it is, for better and for worse, the most American event the world has ever known.