Three theories on why the yuan is weakening

The yuan slid again today, the sixth day in a row it has lost value against the dollar. Or, to be more precise, the People’s Bank of China (PBoC) made the yuan cheaper against the dollar. And though the 0.5% or so drop is really pretty teeny, the fact that that’s the yuan’s most precipitous drop against the dollar since Nov. 2010 invited some hyperbole.

The yuan slid again today, the sixth day in a row it has lost value against the dollar. Or, to be more precise, the People’s Bank of China (PBoC) made the yuan cheaper against the dollar. And though the 0.5% or so drop is really pretty teeny, the fact that that’s the yuan’s most precipitous drop against the dollar since Nov. 2010 invited some hyperbole.

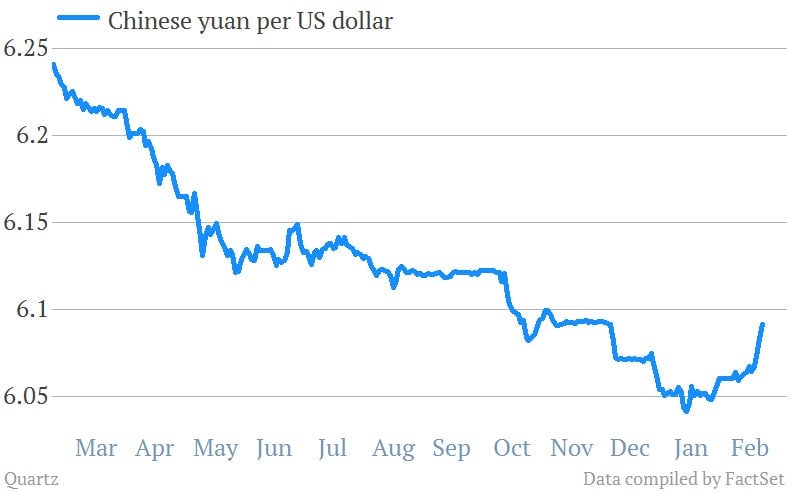

Not that it’s unremarkable. Not counting this week, in the last year the yuan, which the government manages in a 1% band around the dollar, has gained around 3% against the dollar, as the chart below shows.

What remains unclear is what’s behind this week’s drop. Here are some leading theories:

The PBoC is gearing up to loosen the trading band

Some think this drop is a deliberate move on the part of the PBoC, a prelude to the government letting the yuan trade more freely. On Feb. 19 the PBoC said it was planning to widen that trading band (Chinese) in an “orderly” or “regular” manner sometime in 2014. The Wall Street Journal (paywall) reports that the PBOC undertook similar moves before widening the daily trading band in Apr. 2012.

“The band could be broadened as soon as this quarter to as much as 2 percent,” said Banny Lam, co-head of research at Agricultural Bank of China International Securities Ltd, in an interview with Bloomberg.

Sticking it to currency speculators

The government could also be trying to deter speculators from betting on a strengthening yuan. Not only is that pressure bad for export competitiveness, but it has also given rise to a roaring trade in currency arbitrage. And that’s helped inflate the shadow credit system, making China’s finances increasingly precarious.

Currency outflows

Finally, there’s always a possibility that the PBoC is relaxing the rate simply because it now can—because demand for dollars has grown greater than for yuan. That same trend happened in 2012, when capital began seeping out of the country.

What does it all mean?

One hopes it’s not capital outflows. The system needs colossal amounts of liquidity to keep above water. And however destructive hot money is in the long term, at the moment it’s a big source of liquidity, and draining it could cause a seize-up in the financial system (like last June’s). Fortunately, the recent surge in net exports and foreign direct investment makes that possibility seem unlikely.

If, on the other hand, the PBoC is trying to thwart currency speculators, a (presumably temporary) weakening of the fixing rate may actually encourage more bets.

As for the first possibility, the currency band-widening: That could be a big symbolic deal for Chinese financial reform. Some are skeptical, however, that just expanding the band would change much in practice. ”Unless the bank lets the market have more power in deciding the central parity rate [the rate around which the yuan is allowed to trade], the expectation for one-way appreciation would not disappear,” said Liu Dongliang, an analyst with China Merchants Bank, in an interview with Caixin.