A brazen Instagram scam came to an end this week.

On Thursday (Feb. 13), federal authorities arrested Kayla Massa, an Instagram and YouTube “influencer,” charging her with conspiracy to commit bank and wire fraud. She and her accomplices allegedly recruited victims over Instagram, asking them to hand over emptied-out bank cards, with the accounts then being used to deposit large amounts of stolen money.

A complaint unsealed in New Jersey federal court contains details of an audacious scheme that prosecutors say brought in more than $1.5 million.

Social media platforms are filled with individuals hoping to find an easy mark, and the companies that run them have trouble keeping up with bad actors.

The investigation began in July 2018, when the US Postal Service learned that 53 blank money orders had been stolen from the Berlin, New Jersey post office. Thirty of them had been deposited in various bank accounts, all for either $990 or $995. Investigators saw that the money orders were missing a clerk ID, and the date, zip code, and dollar amounts were all printed in the wrong font.

Postal inspectors identified the bank accounts into which the stolen USPS money orders were deposited. One of them belonged to a Barrington, New Jersey resident identified in court filings only as “J.K.” Two of the money orders had been deposited into J.K.’s two accounts at PNC Bank, both for $995.

In an interview with Postal Service criminal agents, J.K. said they had responded to a posting by an Instagram user named “Kayg0ldi.” In direct messages between the two, Kayg0ldi told J.K. that they could earn up to $5,000 by letting Kayg0ldi’s friend use their bank account for an “unspecified, but short, period of time.” The friend had a clothing line, and needed to deposit money in JK’s account as a “tax write-off,” Kayg0ldi explained.

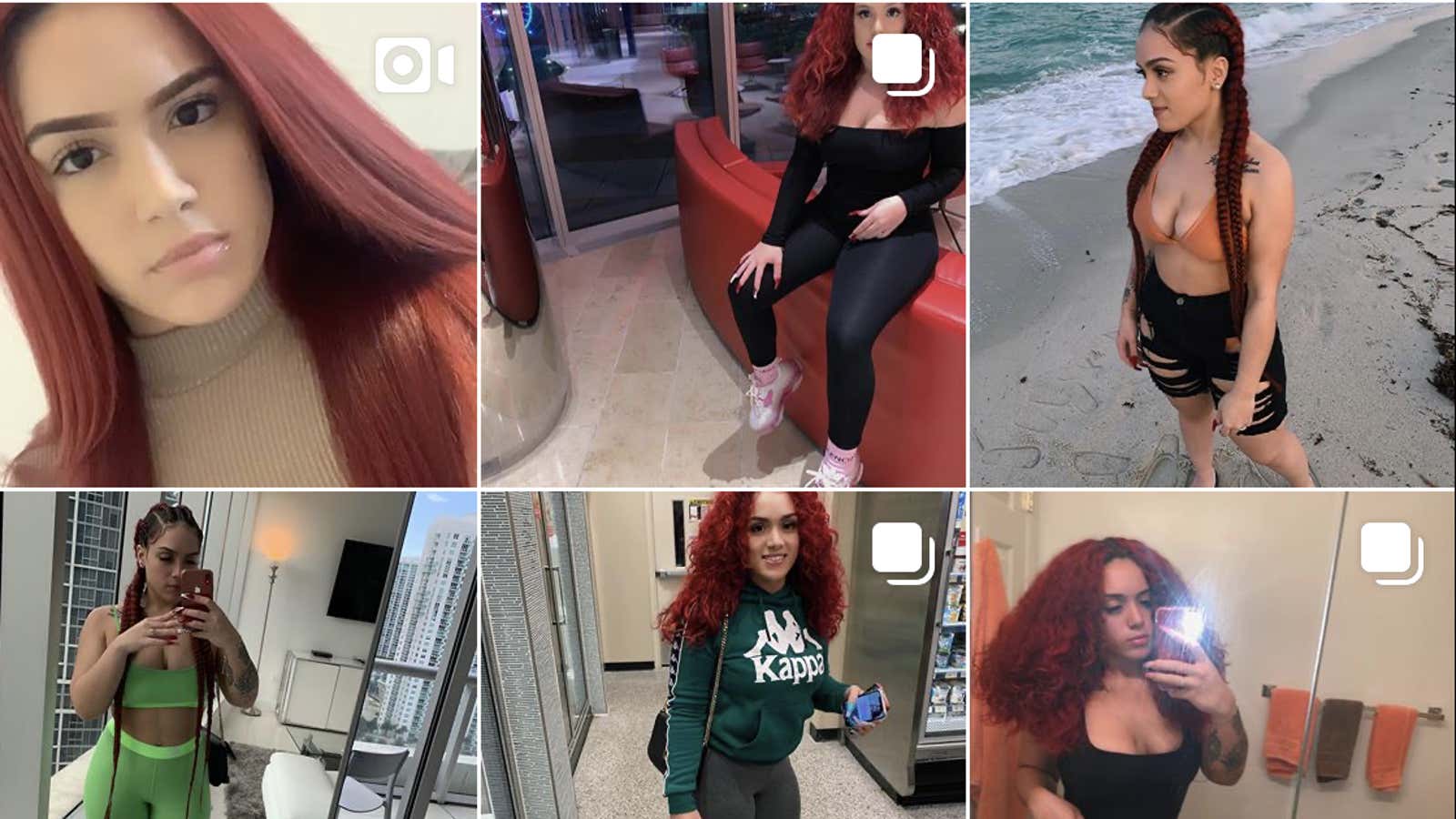

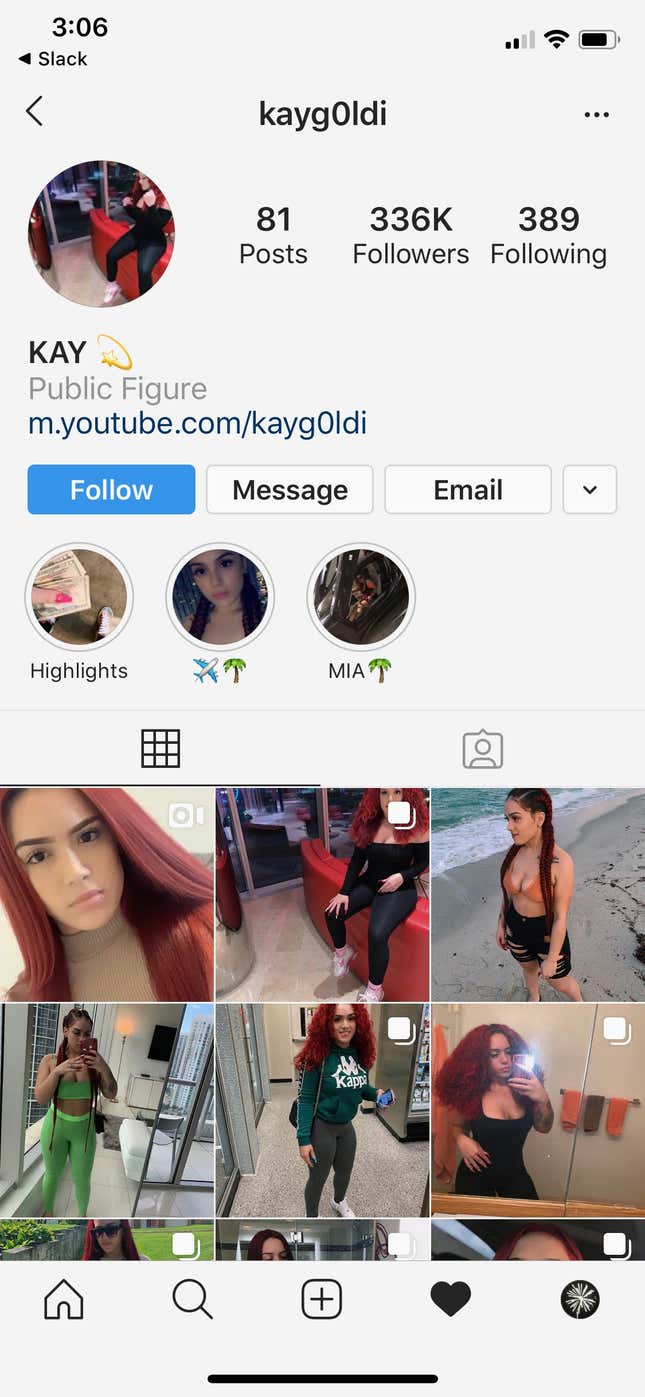

Massa, 22, is identified by prosecutors as a Burlington County, New Jersey resident known as kayg0ldie on Instagram, where she had more than 330,000 followers. (Her account was taken down after Quartz contacted Instagram.) Massa also has a popular YouTube channel, with 107,000 subscribers, where she has posted various vlogs and hair and makeup tutorials.

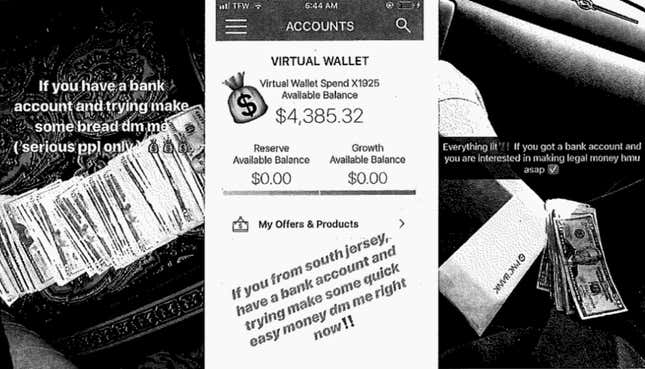

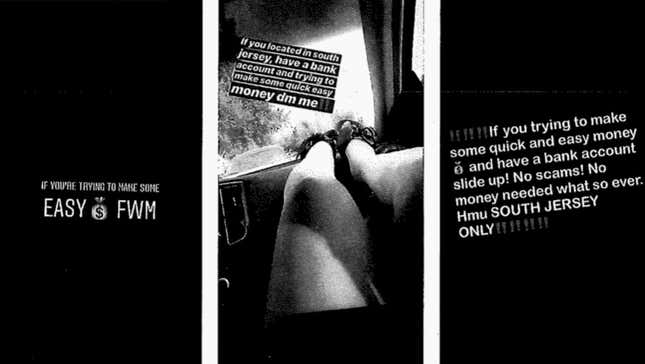

Massa allegedly promoted her scheme through posts on Instagram Stories, featuring stacks of money, screenshots of bank account balances, and money orders. There were videos of people flashing debit cards and large amounts of cash.

“If you have a bank account and trying make some bread dm me (serious ppl only) 💰💰💰,” read one frame caption.

The group also allegedly “advertised” on Facebook and Snapchat.

It was all perfectly legal and legitimate, Massa would allegedly tell her marks. To “falsely allay any fears of losing money,” Massa “encouraged individuals to empty their bank accounts before providing their debit card and PIN,” according to the complaint against her.

J.K. went to a local McDonald’s to meet Massa, who was there with her boyfriend. The deposits would be made at an ATM, so Massa would need J.K.’s debit card, PIN number, and the online login information for the account. Massa reiterated her promise of a quick $5,000, and said she’d return the card “quickly.”

The money order funds were credited to J.K.’s account within a few days, and two purchases for about $1,000 were then made with J.K.’s debit card at a Walmart. A third purchase, for a $450 money order, was made at the Clementon, New Jersey post office (and later cashed at another one). A week after the money was spent, PNC Bank realized the two money orders that had been deposited into J.K.’s account were fraudulent and recalled the funds. J.K.’s account, which now had a negative balance, was written off by PNC as a loss.

J.K. subsequently tried and failed to contact Massa on Instagram in an attempt to find out what was going on, but had been blocked and couldn’t get through.

It was a new spin on an old scam. The funds from the fraudulently obtained money orders and counterfeit checks would clear before the bank discovered the fraud. The ring would then withdraw the cash and often buy new, legitimate money orders with the ill-gotten gains in an attempt to launder it.

C.F., another victim, told investigators that he/she began DMing with Massa in response to social media posts on Instagram. Massa said she had her own “brand” and that she would put C.F. on her payroll, and pay C.F. for the use of his/her account. Massa gave C.F. her phone number and told C.F. to text her. They made plans to meet at a train station in Lindenwold, New Jersey, where C.F. handed over her Capital One debit card and PIN number.

Soon, four Western Union money orders, each for $995, were deposited into C.F.’s bank account. Massa texted C.F. with further instructions, saying that the longer she had C.F.’s card, the more money C.F. would make. She usually kept people’s cards for five full business days, Massa said, saying this would earn C.F. about $2,000.

The next day, C.F. tried to contact Massa on Instagram, but found she had been blocked from Massa’s account, meaning they could not reach her or see her content. C.F. then tried to get in touch with Massa by phone, but Massa had blocked C.F.’s number. Two days after that, the money orders that had been deposited into C.F.’s account were identified as counterfeit and returned. The account was overdrawn by nearly $4,000 and was subsequently closed by Capital One.

Another victim, identified in court documents as “M.D.,” lost $3,738 to Massa’s alleged scheme and had to enter into a payment plan with TD Bank to settle the debt. Another had their account closed and put into collections. When one victim realized early on that they had unwittingly taken part in a fraud scheme, they managed to get in touch with Massa and threatened to report her to the police.

“Do what you gotta do,” Massa replied, according to court documents.

The stolen postal money orders and counterfeit Western Union money orders made up one part of the fraudulent deposit scheme, which is known as “card-cracking.” Counterfeit checks drawn on local businesses—including a car dealership where one of the accused co-conspirators worked—made up the other.

“The more our lives become digitized in one format or another, the more vulnerable we all are to any version of a fraud scheme,” former Secret Service agent James Tomsheck, who spent many years investigating financial crimes, told Quartz.

It was as easy as taking a photograph of a real check, then printing out a copy with a new payee.

Victims of this particular scam appear to have been on the younger side—the court documents indicate some had been minors, and one of the bank accounts in the case was a student account. But people of all ages can be marks on social media. In November, Quartz published an investigation into a precious metals dealer using Facebook ads to microtarget conservative seniors. The company in question had been convincing retirees to convert their savings into vastly overpriced gold and silver coins.

Some months later, police pulled over a black Nissan in Winslow Township, New Jersey. They searched the vehicle and found, among other things, 39 checks from Nissan Turnersville made out to “Keith Williams” that had been shoved in the sunroof. However, there was no one named Keith Williams in the car. Cops also found two Bank of America debit cards with names that didn’t match those of any of the car’s occupants, multiple Bank of America withdrawal slips, and two blank postal money orders.

Nissan Turnersville provided investigators with a list of 697 fraudulent checks that had been issued from its account during the relevant period, totaling more than $128,000. Authorities then visited the 45 or so people into whose accounts the checks had been deposited. All of them told the same story as J.K., C.F., and M.D., though some had responded to posts on Snapchat and Facebook.

In the meantime, another Nissan dealership in the area, Woodbury Nissan, also fell victim to check fraud, totaling slightly less than $14,000.

As it happened, on a phone belonging to the driver of the black Nissan, investigators found a photograph sent from a phone number traced back to a Woodbury Nissan employee who happened to be one of a small handful of people with access to the room where the dealership’s checks were processed. Sixteen other car dealerships and automotive shops nearby had been burned by check fraud around the same time, and all had one thing in common: They all did business with Woodbury Nissan.

By now, investigators had zeroed in on Massa by subpoenaing Instagram for the user’s account info, and obtaining records associated with the phone number Kayg0ldi used to communicate with her victims. Investigators linked all the people who were in the black Nissan back to Massa, and identified numerous other members of Massa’s network. Phone records revealed, among other evidence, messages with other people’s usernames, passwords, last four digits of their social security numbers, and pictures of legitimate business checks.

Although their social engineering skills were high, the alleged co-conspirators were sloppy in covering their tracks. Counterfeit checks had been deposited in bank accounts belonging to Massa’s mother, and at least one money order had been made out to Massa’s sister, Leire, using her real name and address. All of the members of the ring were caught on surveillance video depositing counterfeit checks into, and making ATM withdrawals from, victims’ bank accounts, and buying money orders at area post offices.

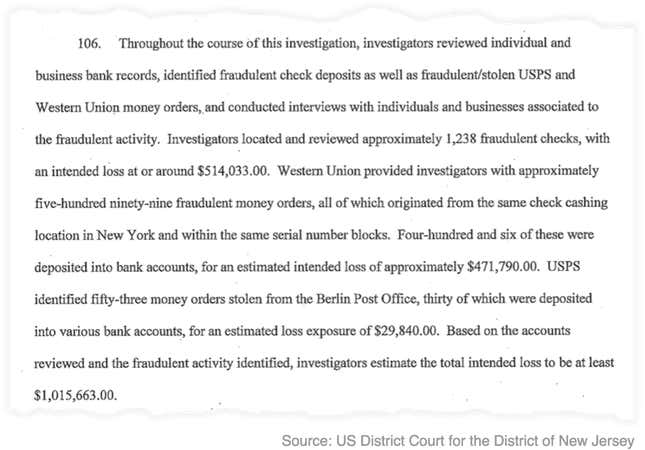

Between May 2018 and February 2020, the ring deposited more than 1,600 fraudulent or counterfeit checks, and more than 650 counterfeit or stolen money orders. Sometimes the fraud was discovered and stopped before any funds were released. Court filings originally reviewed by Quartz did not list the total amount stolen, but said that investigators “estimate the total intended loss to be at least $1,015,663.” The Department of Justice later increased this figure, saying in a press release that the crew had in fact obtained at least $1.5 million.

In all, 10 people including Massa were arrested Thursday, Feb. 13: Leire Massa, 20, who went by “0nlyg0ldenLe”; Kayla Massa’s boyfriend, Jordan Herrin; Leire Massa’s boyfriend, Erasmo Feliciano; William Logan, or “100k_nlb”; former Woodbury Nissan employee Alex Haines; Kevin McDaniels, known online as “chasesir100k”; Jabreel Martin, who went by “1hunit_mill”; Andrew Johnson, or “Savage_Santa”; and Dezhon McCrae, a budding rapper who performs as “YC Woody” and went by “realycwoody” on Instagram.

Christopher O’Malley, Massa’s court-appointed lawyer, declined to comment. Matthew Reilly, a spokesman for the US Attorney’s Office for the District of New Jersey, also declined to comment.

“Scams hurt our community and have no place on Instagram. We have many systems in place to help us catch and stop this activity—including the option to report both content and ads that may include scams,” Stephanie Otway, a spokesperson for Facebook, Instagram’s parent company, told Quartz.

US authorities request information from Facebook more and more every year. In the first half of 2019, they issued more than 9,000 subpoenas to the company, and in 83% of those cases, the company provided information to law enforcement.

This post has been updated to reflect prosecutors now say the scheme brought in over $1.5 million.