The lessons of cherry blossoms are most relevant during the coronavirus pandemic

Since the eighth century, the Japanese have heralded spring’s start—marked by the unfurling petals of cherry blossoms, or sakura—with festivities under flowering trees. The blooms’ arrival serves as a symbol, teaching tool, and an excuse to party.

Since the eighth century, the Japanese have heralded spring’s start—marked by the unfurling petals of cherry blossoms, or sakura—with festivities under flowering trees. The blooms’ arrival serves as a symbol, teaching tool, and an excuse to party.

But 2020 is different, given the coronavirus pandemic. Gathering en masse is strictly prohibited, which means no nature celebrations or picnicking on blankets and getting drunk on booze, floral perfume, and the universe’s beauty.

Instead, around the globe, people feel their lives in a stranglehold, halted by an invisible and deadly enemy.

We need hanami—Japanese for blossom-watching—now more than ever when we’re super stressed and great uncertainty lies ahead. These flowering trees are deep. Their blooms hold secrets that can help put the pandemic, and existence, in perspective.

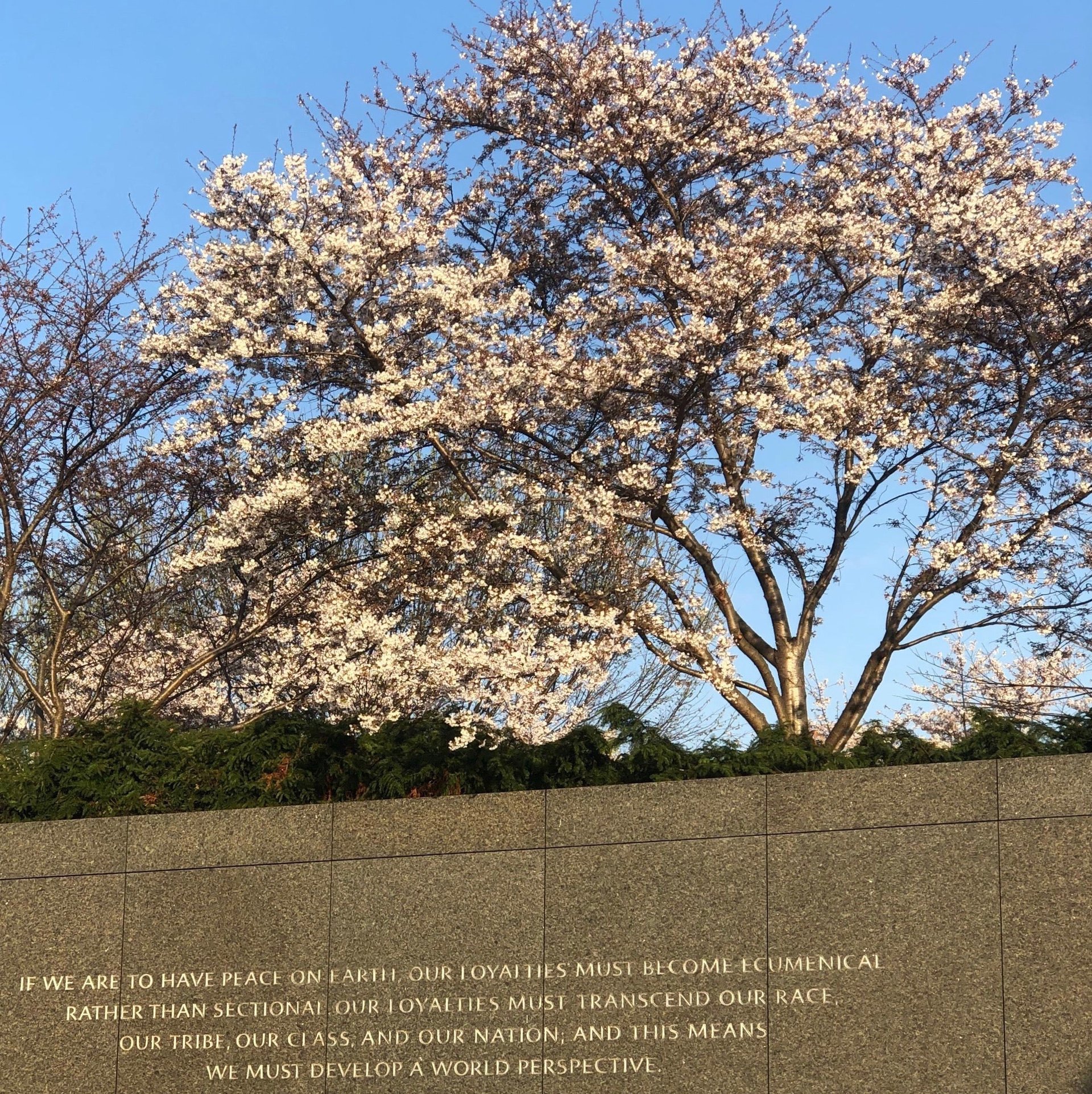

Cherry blossoms aren’t just lovely. They represent life itself, the fragile and finite nature of existence and the interconnectedness of everything.

Sakura as symbol

The blooms are visible for all of two weeks. Their brief lives tell a very short story, or so it seems at first glance.

Cherry blossoms are the haiku version of the long bittersweet novels we humans write over years and decades. All the drama of life and death is compressed in just a few lines.

But it is their inevitable end that makes cherry blossoms’ presence perfect, poignant. Their absence that makes our hearts grow so fond. If they were always there we might not care, much less plan petal parties.

Thus, in the Japanese poetic tradition, their end must be accepted with a certain stoicism. As 18th century Buddhist monk and master poet Kobayashi Issa wrote: without regret/they fall and scatter/cherry blossoms.

No one can get hung up, not us or the flowers. There are forces we cannot thwart, not with our will to live or desire to do business as usual.

The art of detachment

The trick is to carry an understanding that comes easy during hanami and apply it all year, to extend this philosophical outlook.

To be sure, the difficult lesson of detachment is easy to accept when it’s just a poetic notion to consider under an awning of blossoms while drinking sake with pals. Still, truths don’t change, even when our circumstances do. That is no less true now than in Issa’s time.

Most of us aren’t like the master poet and his monastic ilk, actively practicing detachment. We’ve got postmodern problems, like wifi access issues and a global health crisis of epic economic proportions to weather. We’re clamoring for action to take and answers to questions we can’t yet articulate, already nostalgic for the world we knew before quarantines and social distancing though we have only just begun this difficult adventure into the new, secluded future.

It may seem like the lessons of yore no longer apply to our brave new world. But that’s not so. The 18th century poet had plenty of woes, including losing his first two wives and three children, and a home.

Issa, just like us, had to master detachment by learning it the hard way. The people and things he loved were like the spring sakura, he discovered firsthand, delights to be savored in the moment, gifts to be appreciated before they’re yanked away.

As coronavirus death tolls rise worldwide and the economic fallout grows ever more incalculable, we fear for our lives and societies, all while few of our usual consolations are available. We want to know the as-yet-unknowable, to hurry up and get this period over with so that we can get back to community and its comforts—hugs, handshakes, hanging out.

But the only answer now is to detach from that unsatisfiable desire because it just can’t happen, and instead connect with another secret of the sakura and all living things, a truth so profound that your mind is designed to deny it most of the time.

The illusion of self

You may be physically distant from me, but we are not estranged. We are one and the same. Indeed, the pandemic emphasizes this.

Everything is connected, from the germs to the blooms to the humans. That’s why we should be trying to stay away from each other. We’re a single living organism, inextricably linked and inevitably interdependent, all the parts seen and unseen influencing the rest.

Though we are distancing socially, from a cosmic perspective, on Earth, we’re all so close our brains can’t always bear to know it.

“The self is a neuronal fantasy that guides our behavior,” according to University of Sussex professor of cognitive and computational neuroscience Anil Seth. The professor’s mega popular 6.5 million view 2017 TED talk “Your brain hallucinates your conscious reality” argued that self-awareness is a mere mechanism. “Right now, billions of neurons in your brain are working together to generate a conscious experience—and not just any conscious experience, your experience of the world around you and of yourself within it,” Seth explained.

That story of your self isn’t all you are or the thing that proves you exist, though. You can be unconscious and alive, after all. And you can, perhaps, experience being altogether differently, becoming aware of our self—the you that is me and the trees and the flowers they sprout.

Seth calls reality our shared delusion. In reality, we agree we’re beings with stories that begin at birth and end with death.

But sometimes people forget, briefly. They stop being self-conscious, entering a state of flow. Artists, athletes, naturalists, crafters, parents—basically anyone who engages in anything with intensity—have all attested to experiencing a loss of self accompanied by awareness of a larger process.

That connected feeling can be induced chemically, too. Scientific studies on the use of psilocybin show people who take hallucinogens also experience this wider consciousness, which indicates that the sense of self is made by regions of the brain that can be activated or deactivated. The mechanisms that create self-consciousness can be switched off, prompting awareness of a continual communal planetary project involving all that was and will ever be.

Philosophers from numerous traditions have said as much. In his 1966 work, The Book on the Taboo Against Knowing Who You Are, philosopher Alan Watts posited that we aren’t separate individuals. In fact, that perspective is what makes us sad and hostile. We’re a flowing segment in the continuous line of life. “This feeling of being lonely and very temporary visitors in the universe is in flat contradiction to everything known about [humans] and all other living organisms in the sciences,” Watts wrote. “We do not come into this world; we come out of it, as leaves from a tree.”

Speaking of leaves

Cherry blossoms are also conscious, according to some plant biologists. Not everyone agrees, but it increasingly seems that plants and trees show awareness. They speak a sort of biological language, have a sonic thought process that leads them to water, and are extensively connected to a whole network of other living things. They appear to be part of a vast communicating community that scientists are only beginning to comprehend.

We don’t even know yet the full extent to which everything is linked. Yet our fragility and interconnectedness has never been more evident than now as humans stay apart in the name of survival. And these ties—the way everything and everyone is fundamentally related—are also what make predictions so unreliable right now. A lot of forces are at work and calculating all the possible consequences of this global crisis is impossible.

What we can do is learn to live with two competing truths that we’re forever managing but are magnified right now. The universe is confounding and mysterious. But it’s not totally unpredictable, or unreliable.

The sun always rises and sets. The seasons come and go. The cherry blossoms visit briefly each spring. And the people of the world will party under the moonlit blooms again.