Is retail therapy ethical during the coronavirus crisis?

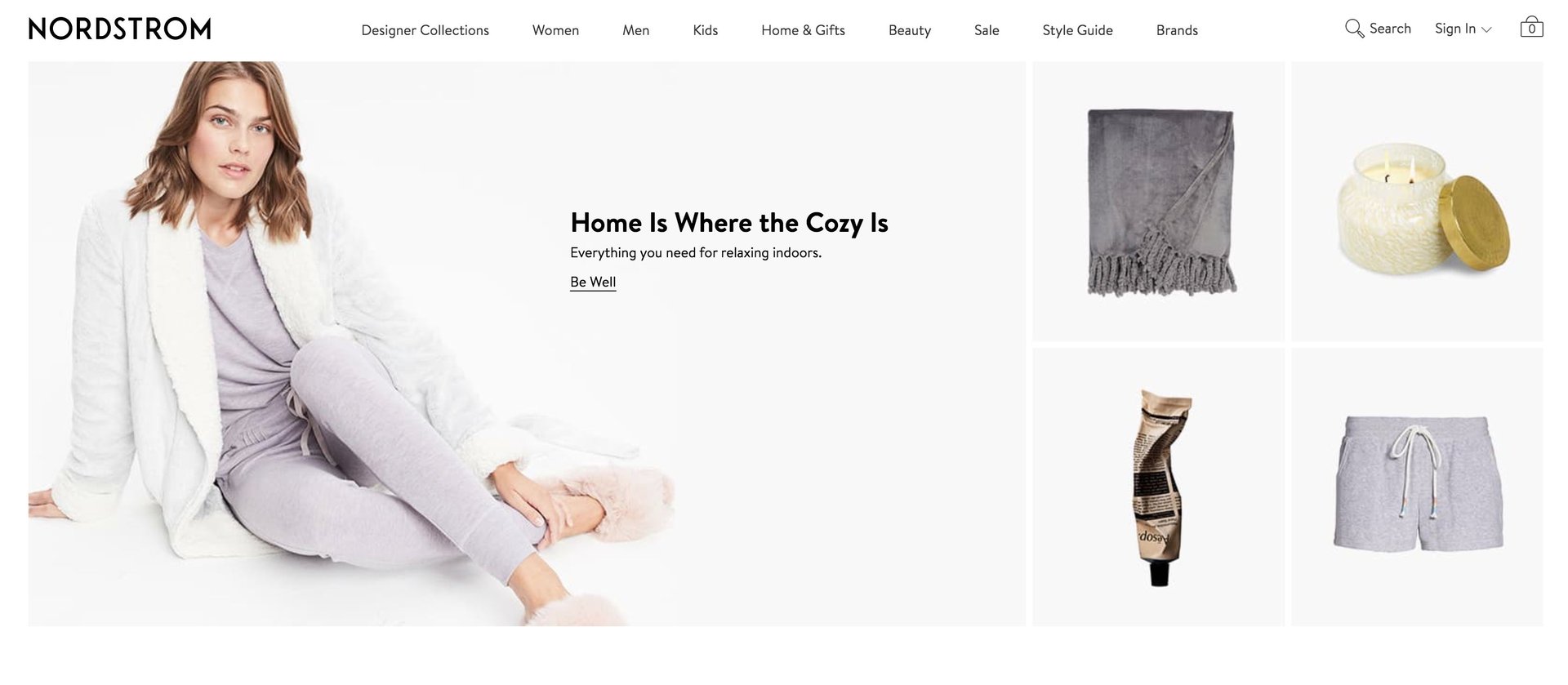

As I read the news online about the coronavirus, it’s impossible not to be distracted by the omnipresence of highly attractive loungewear. Yes, there are stories of aid packages, market slides, and death tolls. But there in the ads are also smartly cropped sweatshirts, drawstring pants in putty shades, and some shearling-lined suede moccasins that look suitable for wearing indoors and out.

As I read the news online about the coronavirus, it’s impossible not to be distracted by the omnipresence of highly attractive loungewear. Yes, there are stories of aid packages, market slides, and death tolls. But there in the ads are also smartly cropped sweatshirts, drawstring pants in putty shades, and some shearling-lined suede moccasins that look suitable for wearing indoors and out.

On one hand, the stressful and uncertain early days of a quarantine seem like a perfect time to upgrade one’s sweatpants and support an ailing economy. Retail therapy is real. (And hey, this fashion site is offering a 20% discount with the code STAYHOME.) On the other, it feels morally indefensible to add an unnecessary package to an already vulnerable and overladen delivery person—especially as heartbreaking and horrific reports emerge of US postal workers and FedEx and UPS drivers going to work with symptoms of the coronavirus for fear of losing their jobs.

So what’s an anxious would-be shopper to do? Is it unethical to channel one’s nerves into our tanking economy with non-essential purchases such as a lipstick to brighten that Zoom meeting, or a hydroponic garden to while away the hours?

Three simple factors

Carissa Véliz, an ethicist and researcher at Oxford University, says ordinary citizens should have three social priorities amidst a pandemic:

1. Avoid contagion as much as possible (ie: stay home).

“Whatever goes against these objectives, all of which help save lives or make people’s lives better, is ethically questionable,” writes Véliz in an email. “What’s tricky is figuring out exactly which actions help all three objectives.”

“In some cases, buying a non-essential product will be more ethical than not buying it. A face cream might not be essential to you, but it might be essential for the family whose livelihood depends on selling it.” Véliz adds that if the product is locally made and hand-delivered from a family business that has taken every precaution to minimize contact and disinfect along the way to leaving the product at your door, that’s a pretty clear green light.

“Their work is not increasing the chances of contagion, as it’s not increasing contact between people. Such activity is not overwhelming crucial systems. And it’s keeping the economy going,” she writes. “Unfortunately, most cases are not so clear cut.”

A virtuous process

I asked Jim Thomas, an epidemiologist at the University of North Carolina and the lead author of the American Public Health Association’s code of ethics, about whether this was an irresponsible moment to upgrade my sweatpants. He called upon his expertise in virtue ethics—an approach that emphasizes morality and motivation over rules or results. Thomas says that when it comes to making morally sound decisions, engaging with the process matters.

“Giving it some thought matters, and being informed matters,” he says. “One of the things I tell my students when I’m teaching ethics, is that it’s not so much the right answer that we’re looking for. But we’re looking for the answer that is morally defensible. Can you show us the math of how you got to where you are, and is it a compelling story?”

And that answer can depend on the person doing the math. “There is a difference between someone who’s wheelchair-bound at home ordering some groceries from Amazon, versus someone who just doesn’t want to go out,” says Thomas. The wheelchair-bound customer has a morally defensible reason to prioritize Amazon’s speed, ease, and reliability. A young and able person tapping out a rush delivery because they’re too deep into Westworld to step out? Not so much.

Doing the math

To be sure, groceries are more essential than a pair of sweats I would be proud to be seen walking the dog in.

So I might start by asking myself how much I really “need” these sweatpants. If I could easily wait it out, there’s a good epidemiological case, if not an economic one, for doing so. Thomas says that since the US is still in the early stages of this pandemic—“on the front end of the curve,” meaning that many people are still vulnerable to infection—it’s a good time to hold off on more frivolous purchases that might further expose delivery workers until cases are on the downswing.

We might also think about the business we are purchasing from. We know that Amazon (which now has confirmed cases at six US warehouses), FedEx, UPS, and the USPS are overwhelmed, and workers stand little to gain financially from having one more package to deliver. If a local boutique, bookstore, or bottle shop is offering pickup, that might be a way to minimize contagion and exposure, avoid burdening delivery-people who say they are being offered little protection, and economically support a business that may be in dire straits.

If there are stores and brands you want to see survive, it’s worth checking their social media accounts to see how they are adapting. Among my own favorites, I’ve seen shops offering limited hours for phone orders and curbside pickup, and expanding their offerings to include more regular provisions. For example, a family-owned liquor store by my office now carries fresh produce and milk, in addition to its usual natural wines and artisanal bitters.

At the larger end of the spectrum, outdoor outfitter Patagonia—which serves as something of a moral compass for the US apparel industry— announced on March 13 it would simply make the decision for its customers, by closing stores and suspending online orders in the interest of protecting workers.

But if you do decide to get something delivered, consider tipping the person who brings it to your door. And then, take it easy on the hand-wringing.

“We need to extend to ourselves a little bit of grace,” says Thomas. “We often wonder: ‘Did I do the right thing? Did I make the right purchase? Did I just make somebody more miserable by making this decision?’ And we can’t know. We just never know that. Life is so complicated and the paths are so complex. But we can try, and it’s the trying that matters.”

The bigger picture

As Alissa Quart wrote in Slate, the coronavirus has laid bare just how vulnerable many American workers are, many of whom now find themselves on the frontline of the pandemic. Or, as Vice’s Jason Koebler put it, “there are two types of people now: online shoppers and the people who serve them.”

That inequality is one we can’t just shop our way out of. Bigger systemic change will come not from mindful purchasing, but from policy shifts at the highest level. While workers at Amazon, the USPS, UPS, and beyond fight for basic, incremental protections such as gloves, masks, and paid sick leave, the US is coming to grips with the consequences for millions of workers who live paycheck-to-paycheck, many without health insurance.

“Although it is important for people to ask themselves what the ethical thing to do is when it comes to shopping, a bigger responsibility lies with companies (especially big ones) and governments,” writes Véliz.

For our own part, customers can ask companies what they’re doing to protect workers, support the ones we feel are doing well, and when election time comes around, pay attention to issues like paid leave, healthcare, and the minimum wage —pandemic or not.