Apple, Google, and Amazon are so profitable because they know what to lose money on

To understand which firms are going to end up dominating the market for tablets and mobile phones, it helps to notice that we now live in an era in which every successful company selling hardware and content is giving something away for free. And the companies that can’t afford to give something away for free are now competing with commodity manufacturers that could drive them into bankruptcy.

To understand which firms are going to end up dominating the market for tablets and mobile phones, it helps to notice that we now live in an era in which every successful company selling hardware and content is giving something away for free. And the companies that can’t afford to give something away for free are now competing with commodity manufacturers that could drive them into bankruptcy.

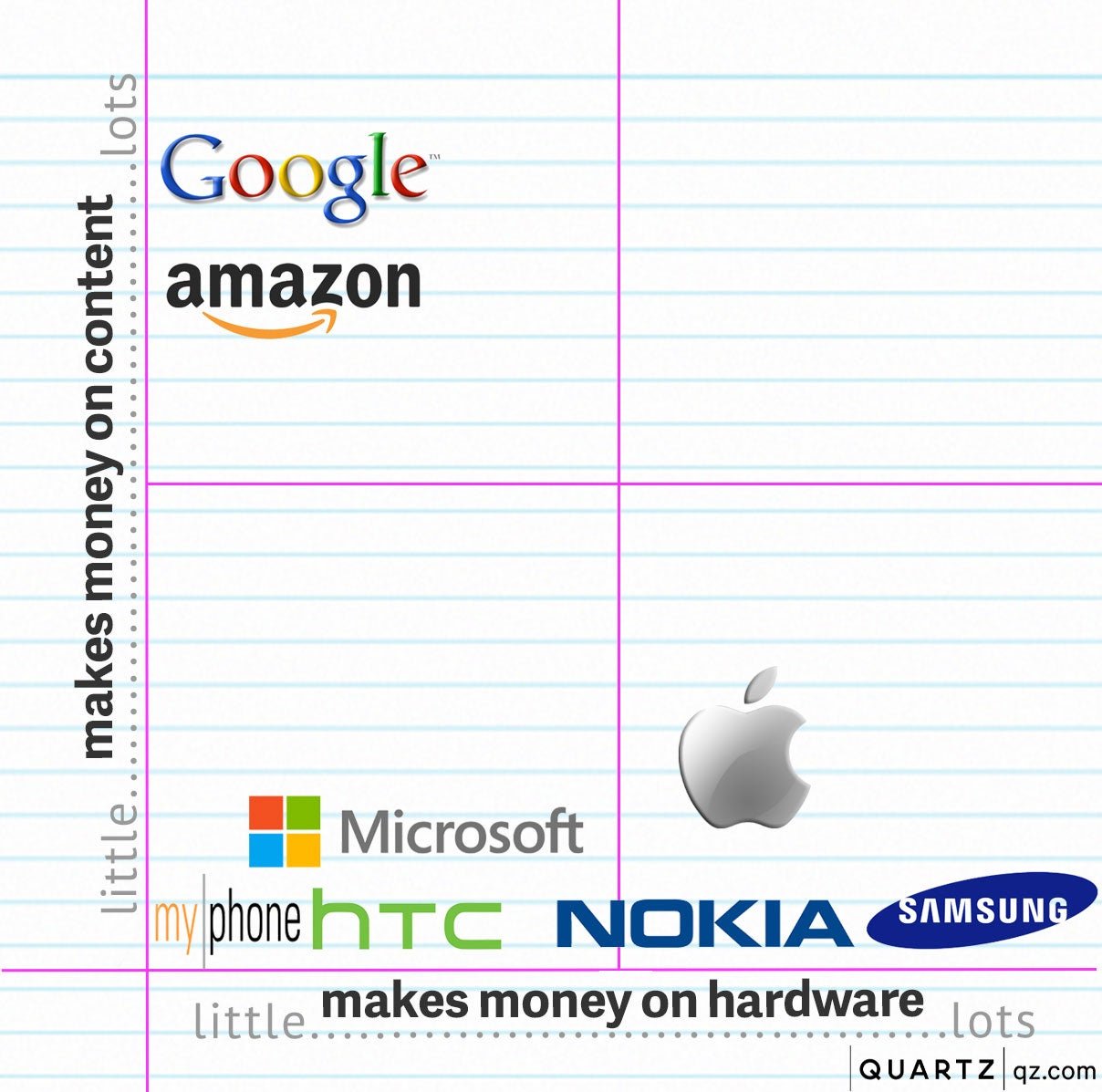

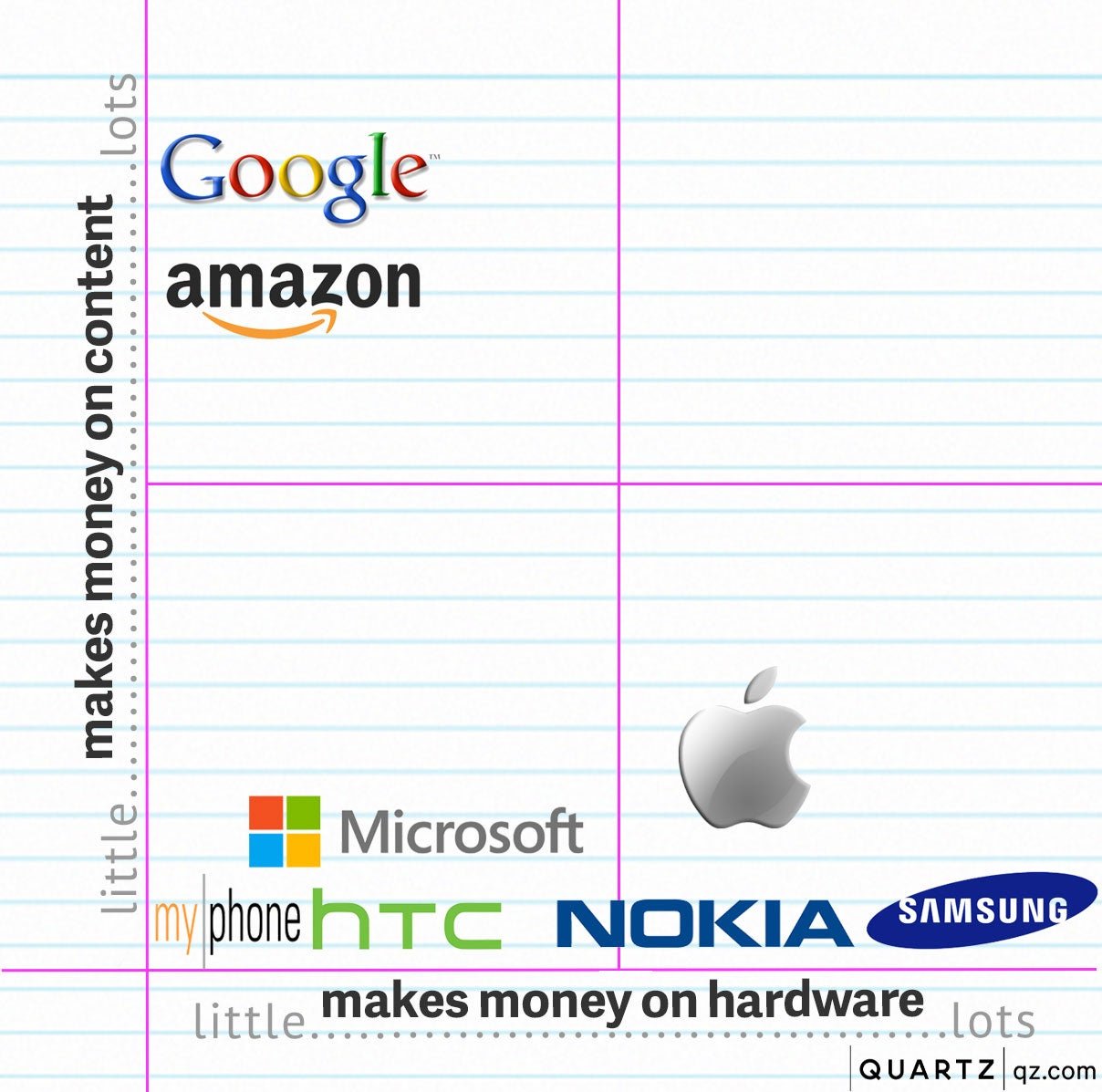

Subsidy—either of hardware by content, or content by hardware—is the common thread running through Apple’s iPad mini (due to be announced tomorrow), Microsoft’s move into hardware with its Surface tablet (due later this week), Nokia’s slow demise, Amazon’s ascent, and the modest success of every regional Android handset manufacturer on the planet. It’s notable that the successful firms have opted for either one model or the other: none makes significant money from both content and hardware.

Here are the implications for the biggest players:

Google practically gives away its hardware, in order to get users onto a mobile experience that it can control, and where it can sell advertising and continue to dominate search.

Google is selling its current Nexus 7 tablet at cost, and is absorbing the associated marketing expenses. For something that costs only $200, it’s a fancy device, so it’s no surprise that the company may have sold a million of them since they became available just three months ago. Google also levies no licensing fees associated with its open-source Android mobile operating system.

So how does Google make money? 96% of Google’s 2011 revenue came from advertising. While Google might not describe itself as a content company, its entire Android business model is built around keeping users searching for and consuming content on its sites. Android tablets made by other manufacturers were selling poorly in comparison to Apple’s iPad, so the company clearly felt the need to step in and create a device compelling enough to get users onto Android, where it can make money from them.

Apple

Apple gives away content, in the sense that it doesn’t make money on it, in order to justify premium pricing.

Apple makes only “a bit over break-even” from the billions of dollars in music, apps and other content that it sells. It does, however, charge a premium for its hardware, achieving margins that none of its competitors can match. As a result, Apple is more profitable than all competing Android handset makers combined.

HTC, Nokia, Microsoft and a universe of commodity hardware

Without either free content or free hardware, brand-name stalwarts of hardware are forced to compete with regional manufacturers who are content with much slimmer profit margins.

The market for mobile devices is becoming “a big barbell with Apple-Samsung at one end and China at the other end,” wrote Vijay Rakesh, an analyst at Sterne Agee, in a recent note to clients. What that means is that users with money to spend are willing to pay a premium for the best hardware that gives them the apps and content they prefer, whether Apple’s or Google’s. And those without so much money are happy to pick up cheap hardware like the kind coming out of commodity tablet and handset manufacturers in China. (This is the same cheap hardware that Google and Amazon are selling through to their customers.)

HTC’s profits are slipping, and Nokia just lost $1.27 billion. Microsoft still makes plenty of money licensing Office, Windows and other software to businesses, but the company is taking a huge risk by moving into hardware with the Surface. Its success or failure will depend largely on the population of apps for the new Windows 8 operating system which runs on Surface, and which is just getting off the ground. If developers fail to flock to the platform, and users fail to follow, the company could find itself competing with the same commodity manufacturers that are wiping out the margins of companies like Nokia.

In this graphic, we’ve deliberately included a company you’ve probably never heard about, a Philippine handset manufacturer called my|phone. It doesn’t make piles of money, but it doesn’t need to. It’s a perfect example of the regional handset manufacturers in emerging markets whose slim profit margins mean stiff competition for larger makers.

Amazon

Amazon, like Google, only makes money when you buy content on the devices it sells at cost.

Perhaps no one has been more vocal about the hardware vs. software subsidy than Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos. “We want to make money when people use our devices, not when people buy our devices,” he told the BBC. In terms of its hardware, Amazon’s Kindle Fire HD tablet is in the same class as Google’s 7 inch Nexus. The difference is that it comes pre-loaded with Amazon’s easy-to-use online store for movies, music, books, periodicals and games. You can use it to browse the web, as you could—much more clunkily—on the Kindle e-reader before it, but that’s not really the point. It’s a way for Amazon to make purchasing and consuming content as easy as possible.

Samsung

Samsung, like Apple, makes its money off hardware. As the largest maker of Android-powered phones, Samsung has essentially outsourced all of its content to Google, for which it pays nothing.

Samsung and Google are the Intel and Microsoft of the 21st century. In the mobile space, it would be difficult for one to succeed without the other. Samsung faces competitive pressures similar to those faced by HTC, Nokia and other makers of hardware powered by other companies’ operating systems and content marketplaces; but because it makes the most sophisticated devices that use Android, it benefits from its reliance on Google rather than suffering for it.

Explaining the iPad mini, and Google’s forthcoming cheaper, larger tablets

Seen from this perspective, it makes sense that Apple’s forthcoming iPad Mini is not that “mini” after all. With a screen that is 40% larger than other “7 inch” tablets like those from Google, Samsung and Amazon, it remains different enough from its competitors to justify Apple’s usual premium. (Rumor has it that the device will be priced between $299 and $349, or at least $100 more expensive than competing tablets of similar size.) Apple can continue to command these prices because of its wealth of apps and content, and not only because of its hardware.

Google, meanwhile, will probably soon release both a larger, 10″ tablet to compete with the original iPad, as well as a remarkably inexpensive, $99 version of its 7″ tablet. By selling its hardware at cost, Google will continue to drive all but no-name, commodity competitors out of the marketplace for low-end devices.

All this means that any firm that now wants to start building mobile devices, and especially tablets, faces an extremely high barrier to entry. It must choose between trying to create a content ecosystem comparable to those belonging to Google, Amazon and Apple—which are already deeply entrenched—or stay small and regional, and accept cutthroat competition and slim margins.