Only the Chinese government knows why the yuan is plunging—but the timing is intriguing

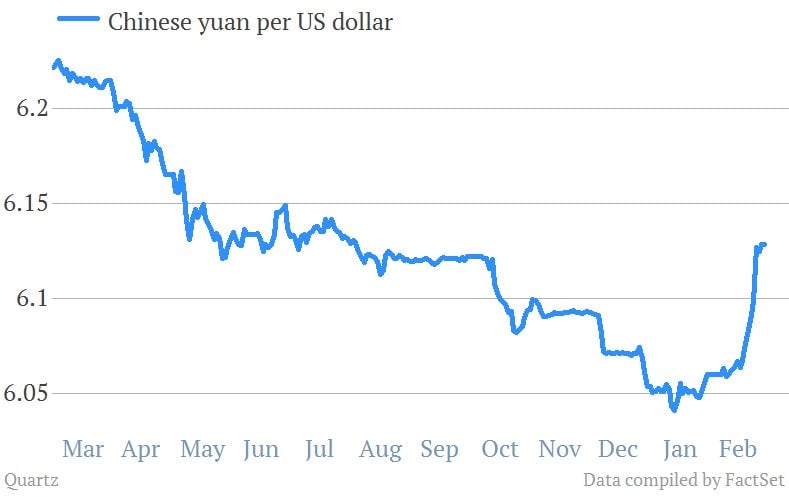

The Chinese yuan plummeted for the ninth consecutive day today, dropping 0.27% against the dollar, its biggest dive since 2005. It finished out the week 0.9% lower than last week—its biggest sequential drop on record—pulverizing yuan traders and rattling markets yet again.

The Chinese yuan plummeted for the ninth consecutive day today, dropping 0.27% against the dollar, its biggest dive since 2005. It finished out the week 0.9% lower than last week—its biggest sequential drop on record—pulverizing yuan traders and rattling markets yet again.

Why is this happening? As we mentioned last week, the Chinese government plans to widen the trading band in an “orderly” fashion this year. On Feb. 26, the People’s Bank of China said two-way fluctuations reflected (link in Chinese) its commitment to letting the market “play a decisive role” and were “conducive” to promoting the yuan’s use internationally.

It’s worth pointing out that the People’s Bank of China, which sets the daily USD-CNY central parity rate, may not be the only factor in what drove down the value today. The PBoC actually set the yuan 10 basis points stronger than the previous day. Today’s weakening hints that traders exchanged yuan for foreign currencies to cover liabilities in the latter.

But the truth is, no one but the Chinese government really knows what’s going on. Last week we flagged the major possibilities, including helping offset recent dollar strength to boost export competitiveness (see The Economist’s chart below) and cracking down on hot money.

An additional upside for the PBoC is what suppressing the yuan’s value might be doing to liquidity conditions. If the PBoC is buying dollars and doing nothing else, it would result in domestic monetary expansion, as Patrick Chovanec of Silvercrest Asset Management explains. That would quell the danger of another liquidity squeeze happening while the government kicks off its annual political conclave, known as the “Two Meetings,” next week.

We can’t know for sure what the PBoC is doing—let alone what its motivations are—but interbank rates, which reflect what banks charge each other to borrow money, have dropped starkly, as Bloomberg’s Tom Orlik flags:

The government often takes great pains to ensure that nothing potentially “embarrassing” happens immediately before or during major political events such as the Two Meetings, the October 1 National Day holiday, or the Party Plenum, explained Chovanec in an email.

“In China, everything’s political, and there’s always something on the political calendar… to justify government intervention to shore up markets,” he says. “One could say that’s part of the problem, why the time for making tough choices always seems to be just around the corner but never arrives.”

Formally agreeing on the pace at which China can reform its finances will probably be high on the agenda next week. Another possible significance to the timing is that, by making the yuan at least appear to fluctuate with the market, the PBoC can claim a “win” for advancing reform. The fact that it is driving currency speculators out of the market also makes what’s normally a politically delicate item of reform an easier sell to more conservative officials at the Two Meetings.