For the first time, a pandemic has brought many of the world’s major economies to a virtual standstill. Supply chains have been disrupted and the free movement of people restricted. No one knows how long this will last, or how severe a blow it will land on the global economy.

But when the dust clears, the air will be clearer. One of the most striking effects of the global spread of Covid-19 has been the reduction in pollution from nitrogen dioxide and carbon dioxide. Millions of people around the world have virtually stopped traveling by car, airplane, or even leaving their homes. Factories are shut down. Manufacturing is grinding to a halt. Personal and professional lives are moving online as social distancing becomes required from Seoul to San Francisco.

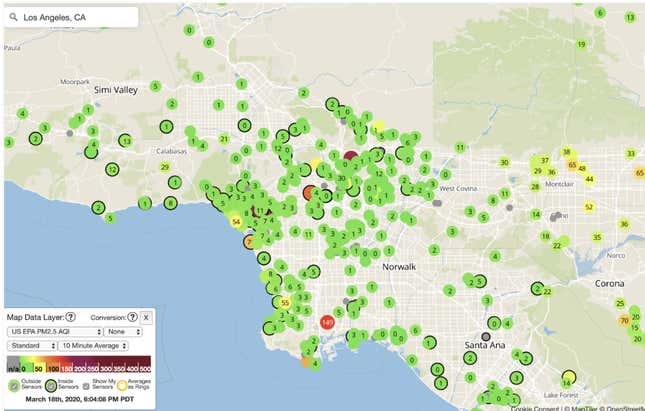

That is already having a profound effect on global emissions. In the urban sprawl of southern California, never known for its fresh air, rush hour air quality is “good.”

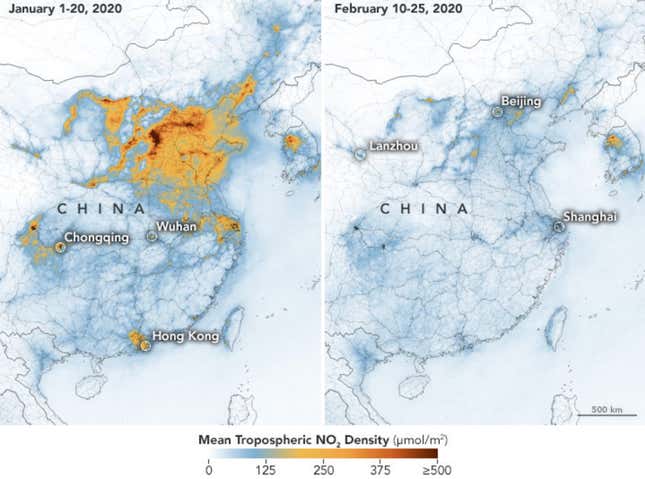

The drop-off was even more extreme in China, where pollution levels plunged in January as coronavirus measures cut industrial output by as much as 40% and slashed emissions by roughly 25%. NASA satellites showed a massive reduction in nitrogen dioxide at the epicenter of the outbreak in Wuhan before spreading across the rest of the country.

Yet how the pandemic affects emissions years from now depends on how it restructures the economy. Once the worst passes, restrictions will ease, commerce will resume, and old behaviors will reassert themselves.

At least, that’s what history suggests.

The airline industry is a prime example, says Khalid Usman of the consulting firm Oliver Wyman. “After past disease outbreaks, demand has returned to normal,” he said. “It hasn’t led to lasting changes in how people travel or how companies do business.” Despite the 1970s oil shock, a recession in the early 1980s, and the 2008 financial crisis, emissions have grown steadily.

But the speed and the scope of the disruption from coronavirus is unprecedented, with more than one in five people around the world in lockdown as national governments struggle to control the spread. If emissions do bounce back, they won’t anytime soon.

The fight against the novel coronavirus is set to drag on much longer than any outbreak since the 1950s. World leaders expect measures against the virus will span the rest of the year and beyond.

Researchers at Imperial College London that modeled different containment strategies to minimize deaths found that some degree of social distancing and quarantining would need to be enforced, at least intermittently, until a vaccine is developed—a process likely to take at least 18 months.

There are growing calls to ease the restrictions, but attempts to get people back to work could only add fuel to the pandemic. “You can have the economy or you can have health care, but not both,” says one epidemiologist.

That timeline makes McKinsey’s best-case scenario (pdf) for the global economy—a drop in GDP growth from 2.5% to 2.0%—far less likely. A deep global recession could cut growth to .5% at a cost of $2 trillion, the United Nations warns.

Long term changes

The immediate impact of coronavirus on industry is already clear. Automakers, transportation, shipping, airlines, hotels, and restaurants have all halted operations or seen red on their balance sheets. Layoffs have begun. Even in China, only now recovering from the initial shutdowns, supply chains are still crippled.

Industries with some of the highest global emissions have been especially hard-hit. The automotive industry, beleaguered by dwindling demand, has seen sales collapse to just 6.2 million vehicles in January, the lowest since 2012, according to GlobalData. China recorded an 80% drop (the biggest monthly drop ever). Airlines have seen travel bookings fall 40% or more, and share prices halved since the outbreak. The International Air Transport Association (IATA) has doubled its estimated impact from Covid-19 to as much as $113 billion if the disease keeps spreading.

But those emissions-reducing losses may be ephemeral. What would truly reset the world’s emissions trajectory will be a shift in the balance of power between fossil fuels and renewables. Covid-19 could change that.

Right now, there are two competing arguments. The first is that investors will finally conclude that fossil fuels are a financial catastrophe. Since the coronavirus outbreak slashed demand for oil, Saudi Arabia and Russia have entered a price war and sent a huge glut of crude into the market, driving down prices by 60%. Bankruptcies have not been far behind. Capital fleeing oil and gas companies could help accelerate the clean energy transition.

But a second argument sees fossil fuels as far more resilient. Investors may reallocate their portfolios away from oil, but without the ability to scale up renewables quickly, the status quo will remain essentially unchanged. With the supply chain (and perhaps financing) for solar and wind power disrupted, it may become even harder to accelerate adoption of renewables. Companies and individuals, attracted by low prices with few fuel substitutes in the transportation sector, will carry on burning fossil fuels.

What’s clear is that the fossil fuel industry has never seen a shock of this magnitude. The surplus of crude from Saudi Arabia and Russia and tanking demand even threatens to send prices into negative territory. “It’s completely uncharted waters for oil and gas companies,” wrote a spokesperson for consulting firm Wood Mackenzie in an email. “The price collapse could be the trigger for a new phase of deep industry restructuring.”

To find out what this means, Quartz spoke with a dozen energy experts around the world for predictions at an unpredictable time. Here’s how this could play out.

Scenario one: Climate wins

The Covid-19 pandemic has already shifted the financial calculus for fossil fuels. Shares in oil and gas firms are tanking. Funds tracking oil and gas stocks are down about 80% since the start of the year, after years of steady declines. Meanwhile renewables, while swooning with the rest of the market, have seen share prices drop by less than half, according to investment research firm Sentieo.

It was more bad news on a terrible year for fossil fuels: The S&P’s utility index outperformed oil and gas sector stocks for the first time in 2020. In a symbolic changing of the guard, Danish wind power developer Orsted, a former oil and gas producer that sold off its fossil fuel assets in 2017, became the region’s biggest energy company, eclipsing Nordic oil and gas giant Equinor on March 9.

“No matter where investors put their money in the oil and gas sector, it’s not safe,” argues Clark Williams-Derry, an energy analyst at the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis. “How many more investors will show up to throw more money at the business model that failed the first time?”

If that sentiment takes hold, it could lead to a rapid and permanent exodus of capital from oil and gas toward renewables, and an acceleration of the ongoing transition to clean energy. In previous economic shocks, oil, gas, and coal investors never left. There were also no real alternatives. But today, solar, wind, and storage are not only available, they’re often cheaper. “The market has clearly been saying oil and gas…as a profit-making venture, it’s yesterday’s story,” says Williams-Derry. “What I think we’re doing now is we’re writing the next story.”

For decades, investors who avoid renewables have justified their choice by pointing to the higher returns, and especially dividends, offered by oil and gas projects. That argument is moot at prices below $35 per barrel, says energy consulting firm Wood Mackenzie. It estimates 85% of oil and gas projects will now see yields fall below 15%.

Not only do renewables deliver similar or better returns at that price, but they carry less risk. The marginal price of fuel—wind or sunshine—is always $0. And the average construction costs for solar and wind decline almost every year. Renewables, still the minority of global energy use, are attracting the lion’s share of new energy investment, topping $288.9 billion in 2018. The US Energy Information Administration estimates 76% of new electricity generating capacity, or 32 GW, will be solar or wind in 2020.

Cheap money, volatile oil prices, and dismal fossil fuel returns could let countries and companies finally unhitch themselves from the fossil fuel roller coaster.

Victim number one will be the US shale industry. Already drowning in a sea of debt, and unable to turn a profit since 2010, the industry faces widespread bankruptcies as oil prices sink to $20 per barrel. Russia, having amassed a massive $500 billion in cash reserves, says it’s comfortable watching oil prices fall below $30 a barrel for as long as a decade. Not so for US shale: The Dallas Federal Reserve puts the average break-even price for US shale operators at $50.

Now, the industry is running out of money, and time. Bank lenders, public markets, and now private equity investors are turning away as the industry furiously cuts costs. Reuters reported on March 12 that North American oil and gas producers slashed spending plans by 30% this month, and the majors followed suit. Occidental cut dividends by 86% while Exxon Mobil, after initially resisting cuts only to see its stock pummeled, says it will now “significantly reduce spending.” The meteoric rise of American oil production, and emissions, is now teetering on a cliff face with the number of active oil rigs in North American falling since January.

This structural shift could be profound, argues David Goldwyn of the Atlantic Council’s energy advisory group. Bankrupt independent oil producers, who have fiercely resisted regulation to reduce flaring and other polluting activities, would likely see their assets snapped up. Oil majors, which can afford to defer production, are more likely to curb extraction and polluting practices. “Ultimately, consolidation would be positive for emissions,” he said.

Scenario two:

Renewables

lose

Plunging EV sales. Rock-bottom oil prices. Global financial worries. Easy capital drying up. The bear argument sees today’s market turmoil derailing the most ambitious spending by governments on cleaner technology and energy efficiency, and low gas prices distracting from low-carbon alternatives. “It will definitely put downward pressure on the appetite for a cleaner energy transition,” asserts Fatih Birol, head of the International Energy Agency.

Birol is not alone. Doherty, an oil specialist at BloombergNEF, does expect that this crisis will shift the fundamental emissions picture. Transportation still relies on fossil fuels such as diesel, gasoline, jet fuel, and natural gas for more than 98% of total energy. Low prices will keep drivers close to the gas pump. If revived demand causes prices to spike, few immediate alternatives exist.

Unless coronavirus becomes the new normal, emissions are going to rise, if slightly slower than before. “In order for this to be a permanent dip, you would need an immediate substitute to stand in,” said Doherty. “I don’t think this is going to be a long term story.”

The one exception is electric vehicles—and even there, it’s a mixed outlook. Today’s cheap oil is likely to delay price parity between clean cars and conventional autos by a year or two, reports Morgan Stanley in a March 9 research note. “We believe the long-term growth prospects of EVs remain solid,” it said. But automobile sales have collapsed across the board. After steady growth in EV sales, last year annual sales rose by only 9% and EV sales accounted for 2.5% of the total, reports EV Volumes. Coronavirus could dent prospects by crushing new sales, and crimping automakers’ balance sheets (they’re already cutting back on manufacturing).

In the electricity sector, the collapse of oil and gas prices is unlikely to immediately change emissions. Oil is rarely used to generate electricity, and the low, low price of natural gas will sustain the construction boom in new natural gas plants. That will displace higher-emitting coal plants, but lock in new emissions as these plants operate for decades.

Meanwhile, renewables have been hit as supply chains and financing plans are upended. China’s wind industry is expected to see an 8% dropoff in 24 GW of new wind power installations after the coronavirus closed factories and halted construction in China. Solar may see its first year of declining installations since the 1980s as global demand drops about 10%, Bloomberg New Energy Finance forecasts.

Even a wholesale shift in the investment climate will not be enough to dent emissions, says Charlie Bloch, an energy expert at the Rocky Mountain Institute. If institutional investors want to rebalance their portfolios, there aren’t enough blue-chip clean energy stocks go around. There are scant few clean energy “majors.” One of the largest petroleum firms, Royal Dutch Shell, brought in almost $400 billion last year, more than 20 times one of the largest renewables company, NextEra Energy.

“The divestment side of divest-invest is the easy part,” he wrote by email. “Some call this the Exxon-Tesla-Apple quandary. You can dump Exxon but might just rebalance to Apple rather than Tesla.” Building a renewable energy firm the size of Exxon Mobil will require a steady influx of revenue, and time.

It’s too early to say what the emissions result will be given the competing forces. John Bistline, an energy and climate analyst at the industry-led Electric Power Research Institute, predicted lower oil and gas prices will spur demand, while the coronavirus response may depress or delay investments in alternatives.

What is sure to brighten the outlook for the growth of renewables? Bistline looked at the factors driving decisions in clean energy in a study in the journal Environmental Research Letters. He found nearly 70% of renewables growth can be explained by the cost of wind and solar projects and governments’ carbon policies. The price of fossil fuels, ultimately, will have a limited impact.

Recovery plans

The economic stimuli plans countries adopt will determine which scenario plays out. As the specter of a recession grows, countries are drawing up plans to pump trillions of dollars into ailing economies from China to the United States.

For now, this mostly consists of emergency funding, health measures, and the safety net. But soon, these governments may be forced to boost employment and consumption. That usually means spending heavily—and labor-intensive sectors such as energy and infrastructure are prime targets.

In the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act, passed to combat the 2008 financial crisis, the Obama Administration designed what amounted to a $90 billion clean energy bill in the broader stimulus package, says Michael Grunwald, a journalist who wrote a book on the stimulus plan. It was the “biggest clean energy bill in US history,” he argues. Without it, it’s unlikely a cost-competitive wind and solar sector would exist today.

This opens up a political opportunity to legislate a renewables support package that agrees with the economics, argue financial analysts at Carbon Tracker: “Politicians can simultaneously reduce pollution, reduce costs, gain votes, and enhance national influence.” So far, the White House hasn’t agreed. It signed off on a $2 trillion bailout with $50 billion for the commercial aviation industry, no greenhouse gas emissions conditions attached.

This time, however, the economics of clean energy may make fossil fuels a bad investment.