Covid-19 is about to reach US farms in a major test for food supply chains

One of the largest farmworker unions in the US says early polling of farm laborers suggests operators of some of the nation’s largest fresh produce farms aren’t taking steps to protect fieldworkers from the spread of Covid-19. That’s worrying news for a food supply chain that experts, so far, have described as robust and resilient in the face of the disease caused by the coronavirus SARS-CoV-2.

One of the largest farmworker unions in the US says early polling of farm laborers suggests operators of some of the nation’s largest fresh produce farms aren’t taking steps to protect fieldworkers from the spread of Covid-19. That’s worrying news for a food supply chain that experts, so far, have described as robust and resilient in the face of the disease caused by the coronavirus SARS-CoV-2.

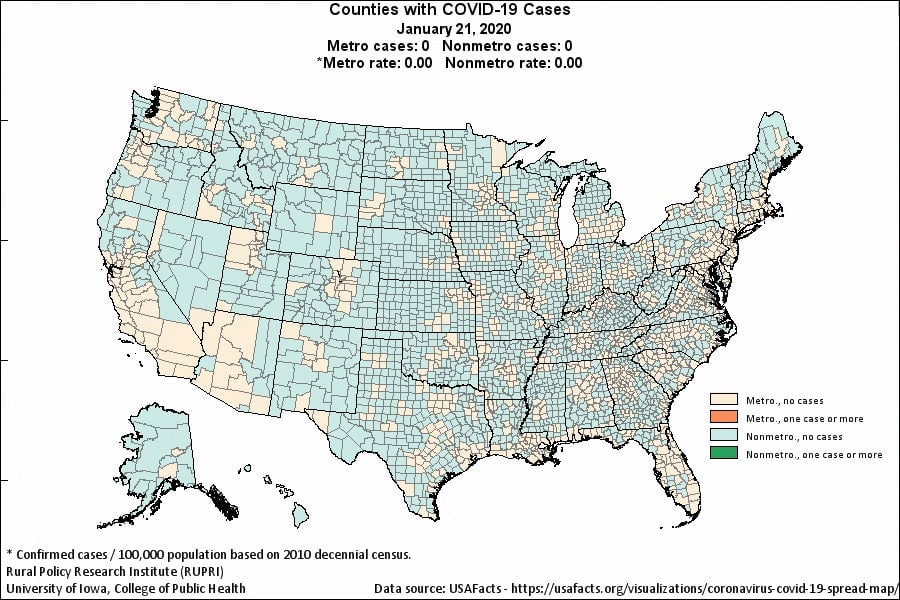

The nature of how the coronavirus spreads—from person to person, through droplets from coughs or sneezes, and transferred on surfaces—means that outbreaks have concentrated first in densely-populated urban and suburban zones. But it will reach rural farming areas on a delay (pdf), according to data collected (and visualized over time) by the University of Iowa’s Rural Policy Research Institute.

That means any farmers who have not been proactive about protecting their workers may have already unwittingly invited the virus into the food supply chain.

Farmworker unions represent a fraction of the nearly 888,000 people hired to pick fresh produce in US crops and groves, most of which are in central California, Florida, Washington state, and Texas. Still, insight from fieldworkers can shed light on what’s happening across the fractured landscape of independent farms.

“Unfortunately, I wish I could say more is being done,” says Armando Elenes, the secretary treasurer of United Farm Workers, a California-based farmworkers union with between 8,000 and 10,000 members. The union regularly polls workers through social media to get a sense of what pickers are experiencing on the job. It isn’t scientific, Elenes cautioned, but the results are concerning.

“As of [March 30], 77% of workers are reporting that nothing has really changed,” he says. “That’s really alarming for farmworkers because they feel obligated. If they don’t go to work, they don’t get a paycheck.”

If that polling accurately reflects what’s happening—or not happening—on farms across the US, it could have a global impact. The more than 400 commodities grown in California represent 13% of US agricultural value, totaling some $50 billion in business each year. For a sense of how consolidated agriculture is, consider that just two California farms supply about 85% of US carrots. If the virus were to disrupt production at the largest of the state’s 77,500 farms, it would be felt globally; a 2018 report (pdf) by the state’s department of food and agriculture put its combined agricultural export value at $20.5 billion.

Supply experts feel optimistic about how the food supply chains have reacted to the spread of Covid-19. They are quick to praise the work at the ends of supply chains, where grocery stores have dealt with an intense round of consumer stockpiling.

But they generally agree that the biggest point of weakness is likely at the very beginning of the chain, on the farms. Daniel Stanton is a former executive at Caterpillar who has taught at supply chain management at colleges and authored Supply Chain Management for Dummies. As he thinks about how the food system gets goods from farms to grocery stores, Stanton says his top concern is whether farmers and ranchers are protecting their workers from getting the virus.

The threat is higher for some areas of agriculture than others, says Ananth Iyer, a supply chain and operations management expert at Purdue University’s Krannert School of Management, depending on how much they rely on human labor.

The largest grain and soybean operations in US Midwestern states, France, Russia, Ukraine, Turkey, Australia, China, and India, are mostly automated. Large planting and harvesting tractors can get the job done with minimal human interaction.

“It’s a different ballgame in respect to grapes, tomatoes, and avocados,” Iyer says, noting that harvesting fresh fruits and vegetables often requires the gentler handiwork of human pickers.

A proactive response to the virus would involve changing daily workflows that gather many laborers in the same space, where it’s harder to practice the social distancing encouraged by health experts. Morning meetings for disseminating marching orders would have to be broken into smaller groups. Transporting pickers to harvesting fields and groves—which often involves packing workers into vans for drives that can last more than half-an-hour—would have to be staggered. And daily lunch breaks would have to be spread out for workers to promote social distancing.

The people who oversee agricultural operations have every market-based reason to implement and ensure laborers abide by rules that promote safer working conditions, Iyers says. For those who don’t, a sick and incapacitated workforce could set off a chain reaction of problems that last years.

“If we don’t have the people, supply will decrease,” Iyer says. “If supplies decrease and demand remains the same, prices will go up. At some point, customers shift what they eat, and once they give up on it they go elsewhere.”

Iyer adds that it can take years and lots of marketing money to nudge people back toward buying certain foods with regularity.

“I’m hoping executives at every stage of the supply chain are anticipating these things and putting pieces in place to address them,” he says.

For some, this appears to be the case. Coral Gables, Florida-based Fresh Del Monte Produce Inc. is one of the largest distributors of fresh fruit and vegetables, bringing in close to $4.5 billion in sales in 2019, with a gross profit of $312 million. In a March 24 press release, the company said it has incorporated more hand-washing practices and has also reduced the number of employees working on its farms, packing houses, port operations, and production facilities at any given time.

“Any employees showing signs of illness are immediately segregated from the workforce and monitored before being allowed to return,” the statement said. Even these precautions may not go far enough, as the virus is often spread by people who are asymptomatic.

The threat is not just economic. It’s also very human. It is estimated that half the laborers on US farms are undocumented immigrants, according to the US Department of Agriculture. Collectively, these workers pump billions of dollars in taxes into the US economy each year, but they are not eligible for federal unemployment insurance benefits should they lose their jobs or fall ill. They also are not included in the $2 trillion stimulus package passed by Congress, part of a wide-ranging relief plan for businesses and people affected by the spread of Covid-19.

Asked about the compelling market incentives for growing operations to adopt safer practices, Elenes explains that some believe changes will cut into overall farm efficiency.

“They are putting profits over people,” he says.

The next several of weeks will be telling for the US, as the virus reaches further into farming communities and a true picture of their preparedness is revealed. As the food supply chain waits for that to happen, it will be important for consumers to keep the situation in context, says Yossi Sheffi, a professor of engineering systems at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

“Food is grown all over the United States, it’s not likely that all these farming communities will be hit at once,” Sheffi says. “Some will be hit harder than others.”

The current situation, and the possibility of disruption in the food system, has Sheffi recalling his childhood in Israel, where his family experienced temporary shortages of certain foods. During an egg shortage, for instance, his mother would have him eat seven olives a day because she believed they collectively had as much protein as an egg. Sheffi’s point is clear: For the average consumer, intermittent shortages of specific foods won’t be devastating.

“Even if you say you don’t have avocados for some weeks, you don’t have avocados, it’s not the end of the world,” he says. ”Let’s make sure the doctors and nurses get all the equipment they need. Let’s make sure the agricultural workers get all the equipment they need.”