The US Supreme Court just sided with Republicans in the first coronavirus-related election case

The US Supreme Court had one day to decide the first in what will surely be a slew of coronavirus-related cases. This one concerned the April 7 Wisconsin general and presidential primary elections and an extension for mail-in ballots ordered by a lower court late last week.

The US Supreme Court had one day to decide the first in what will surely be a slew of coronavirus-related cases. This one concerned the April 7 Wisconsin general and presidential primary elections and an extension for mail-in ballots ordered by a lower court late last week.

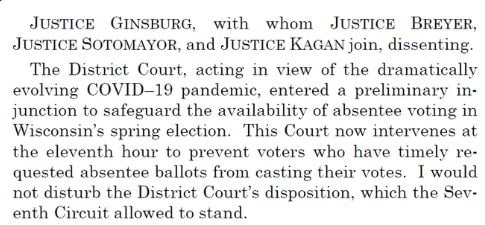

In a 5-4 decision, with the conservative justices all joining to approve and the progressives dissenting, the high court sided with the Republican National Committee. It granted a request for a partial stay that limits an extension on mail-in ballots, which would have been sent in and counted until April 13. The majority said the question presented was narrow and technical and concluded that Wisconsin voters would still be able to vote safely because ballots mailed out by tomorrow could still be counted until April 13.

While many states have delayed primaries due to the pandemic and the public health threat posed by people congregating at polling locations, Wisconsin’s legislature declined to do so because some positions at stake—mayoral, county, and judicial races—have terms that begin on April 20.

Last week, a federal district court judge lamented the legislature’s failure to change the election date and responded to the Democratic National Committee’s request for an extension of the mail-in ballot deadline, giving Wisconsinites until April 13 to get their votes mailed in and counted. Now, voters—many of whom are still waiting on ballots—will have to mail them out by tomorrow or risk infection by going to polling locations to vote.

A flurry of filings

The RNC turned to the high court this weekend, requesting a partial stay and saying that any ballot postmarked after April 7 should not count, even if it arrives by April 13. An unprecedented pandemic shouldn’t lead to last-minute changes, the RNC claimed.

In its reply brief, the DNC argued that this partial stay request would disenfranchise thousands of voters, noting that the pandemic already left many in the lurch. The lower court’s order was simply a compromise with the undeniable reality that the coronavirus crisis had changed everything about American life—except the Wisconsin legislature’s determination to hold an election, of course. It might very well lead to delays in mail delivery, too.

The DNC argued that staying the extension was tantamount to endangering public health by encouraging voters to choose between their right to cast a ballot and their desire to stay safe from contagion. It asked the high court to decline to review the lower court order and believes that any vote that comes with a postmark by April 13 must be counted because the state can’t just operate as if nothing unusual is happening.

More than one million voters have requested mail-in ballots—four times more than usual—and the state has struggled to get those out to people in a timely fashion. As it stands, even with an extension, it’s likely many will end up disenfranchised.

All of these briefs—two from the RNC and one from the DNC—were filed in quick succession between Saturday afternoon and Sunday evening. The justices had little time to consider the arguments, given the fact that the election takes place on Tuesday. But the novel coronavirus is creating all kinds of new situations across the nation, raising a slew of unique questions that the high court will surely have to contend with as cases make their way through lower tribunals.

The waiting game

Court commentators and watchdogs anxiously refreshed the online docket for an answer from the justices all day today, with some sincerely hopeful the highest tribunal will overcome political divisions in a time of crisis and others somewhat cynically quipping on Twitter. Election law expert and Florida State University law professor Michael Morley was in the sincere camp, saying the importance of a safe election is something all people can agree on, whatever their political persuasion.

Meanwhile, Cristian Farias, writer-in-residence at Columbia University’s Knight First Amendment Institute and a New York Times contributor, expressed a similar sentiment, only somewhat more ironically.

Wisconsin officials had no idea what to make of the situation.

Ultimately, the cynics were proven right. By agreeing to review the lower court order, the justices effectively found for the RNC and joined a coalition of conservatives in government who have been pressing for the Wisconsin election, deadly pandemic or no.

A wrinkle in time

While everyone was waiting anxiously for the Supreme Court to decide, Wisconsin’s Democratic governor Tony Evers this afternoon invoked emergency powers and issued an order delaying in-person voting until June, allowing people in positions up for election to remain in place until then. Evers’ order chides the RNC, without naming names, for creating more confusion in an exceptionally chaotic election season by challenging the lower court extension for mail-in ballots. “The intervening parties…immediately appealed the case to the US Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit and, most recently, the Supreme Court of the United States, potentially jeopardizing the commonsense relief ordered…and creating further uncertainty,” he stated.

Localities have closed polling places throughout the state already and the governor called for a special legislative session to be held on the afternoon of April 7, but Republican legislators immediately blocked Evers’ order by turning to the state Supreme Court for help. A panel of four Republican judges invalidated the order while two Democrats approved it, so there is another possible appeal in the making. All that remains valid in Evers’ order, the court ruled, is tomorrow’s legislative session. Plus, there’s another matter pending in Milwaukee, with activists challenging opening polls locally.

In sum, Wisconsin’s controversial pandemic election remains up in the (infected) air.