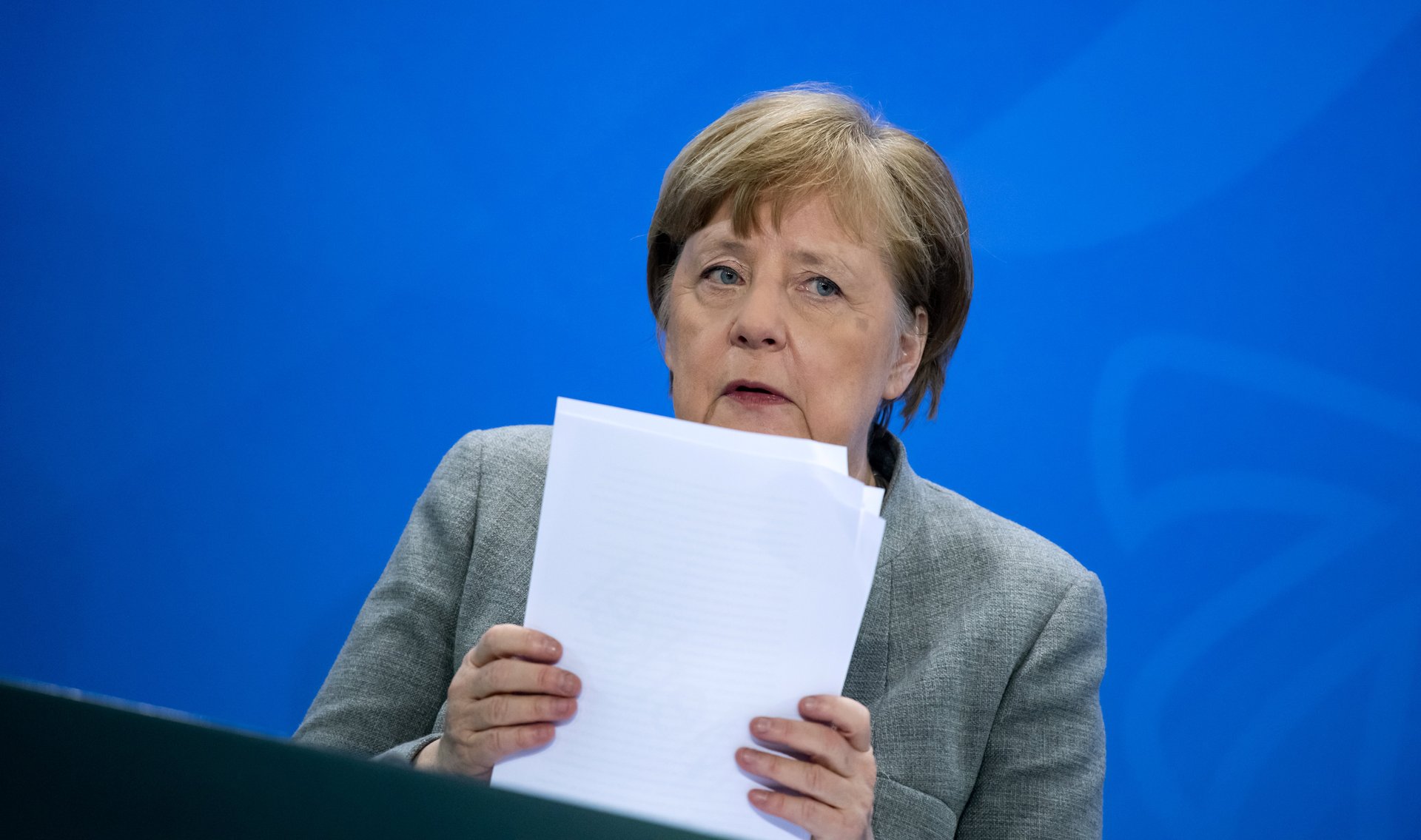

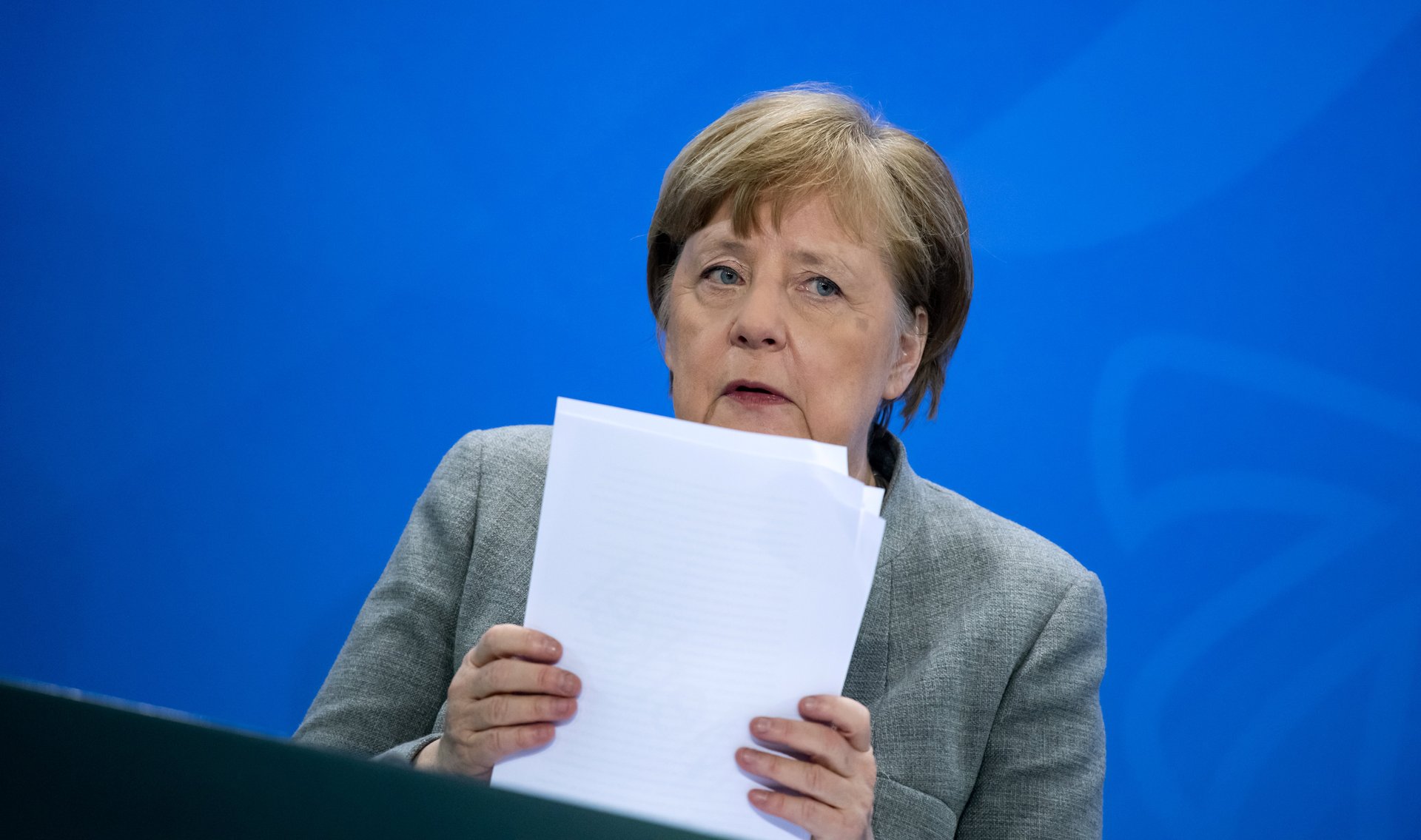

Angela Merkel gave one of the clearest explanations of how coronavirus transmission works

We don’t often expect politicians to grasp the nitty gritty of the mathematical modelling of infectious diseases, let alone explain it in a concise and accurate manner.

We don’t often expect politicians to grasp the nitty gritty of the mathematical modelling of infectious diseases, let alone explain it in a concise and accurate manner.

German chancellor Angela Merkel—who has a doctorate in physics—just did both those things, and it’s a clear demonstration of how important it is for policy makers to understand the nuts and bolts of science when dealing with a public health emergency like the coronavirus pandemic.

Speaking at a conference yesterday, Merkel outlined plans for the country to slowly ease out of its lockdown measures after achieving what she called “fragile intermediate success” in the fight against Covid-19. The steps will have to be incremental, lest there’s a resurgence in cases, starting with a partial re-opening of shops next week and schools on May 4, with a meeting at the end of the month to discuss how to proceed into May.

As societies begin to contemplate how to re-start their economies after weeks of shutdowns, epidemiologists have urged a multi-cycle strategy of “suppression and lift:” a regimen of relaxing and tightening social distancing measures to fine-tune them, so that they are just right for a particular population at a particular time. The idea is to relax the measures when case growth has fallen sufficiently, but to tighten them again if infections again start to spread. Hong Kong and Singapore, for example, are already testing out this strategy.

At the core of the “suppress and lift” strategy is one key number: Rt, or the real-time effective reproductive number. Rt tells us a virus’s actual transmission rate at a given time, t. That is, in a particular population at a particular time, how many other people will catch the disease from a single infected person?

This is the concept that Merkel explained so well yesterday. She noted that the Rt in Germany was currently around one, meaning that on average a person with the virus infects one other person. One is the critical threshold: below one, the epidemic gradually fades out. Above one, it will grow, possibly exponentially. (Hong Kong has a dashboard showing a frequently updated Rt; the latest Rt is just above 0.3.)

Merkel then sketched out what it would mean if Germany’s Rt edged up to 1.1.

“If we get to the point where everybody infects 1.1 people, then by October we will reach the capacity level of our health system, with the assumed level of intensive care beds,” she said.

And if it edges up further still, to 1.2, “everyone is infecting 20% more.”

But 20% is arguably an abstract number, and hard for the average citizen to grasp. Merkel seemed to recognize this, and explained the percentage more concretely: “Out of five people, one infects two and the rest one.” At this rate, Germany’s health care system will reach its limit in July. At an Rt of 1.3, the health care system maxes out in June.

“So you see what little leeway we have,” she said.

Germany currently has more than 134,753 confirmed cases, which is not far off of Italy’s 165,155, according to Johns Hopkins University’s Covid-19 tracker. But its death toll of 3,804 is a fraction of Italy’s 21,645, even though its first confirmed case was detected before Italy. One of the key factors that helped Germany keep the pandemic from spiralling out of control was timely and stringent contact tracing, which allowed authorities to test and isolate those who’ve been infected, buying the country crucial time to ramp up their pandemic defences.