The pandemic shows the pressing need for widespread marijuana legalization

In 1971, a group of high school students in San Rafael, California went in search of treasure. They had a map to a secret marijuana grove and a code for the bounty growing there, referring to the herbal remedy as “420” because they’d gather for the quest every afternoon at 4:20.

In 1971, a group of high school students in San Rafael, California went in search of treasure. They had a map to a secret marijuana grove and a code for the bounty growing there, referring to the herbal remedy as “420” because they’d gather for the quest every afternoon at 4:20.

The code was critical because weed was illegal in California then and one of these bounty hunters, Jeff Noel, was the son of a state policeman who was none too keen on his son’s hunt for herb.

Ultimately, the treasure eluded the students. They never found the grove. But they did make a lasting contribution to the counterculture, coining a codeword for marijuana, which led to the celebration of an unofficial holiday for ganja every April 20 in the US.

Nearly half a century since the students of San Rafael spoke in code and smoked in secret, weed’s role in global culture has transformed almost entirely. It’s been widely decriminalized and legalized and commoditized. The notion of the stoner has evolved from sleepy hippy with no ambition to the progressive businessperson with a marijuana company listed on a stock exchange. Investors are interested in trees, governments want the tax money, and scientists are studying its healing powers.

Eleven US states and the District of Columbia have legalized marijuana, and 18 states have decriminalized it, removing some penalties. There have been numerous bills proposed in Congress to legalize weed at the federal level as well. And in the interim, the government isn’t above collecting taxes from marijuana businesses. The people—2 out of every 3 Americans, according to data from the American Civil Liberties Union—support legalization.

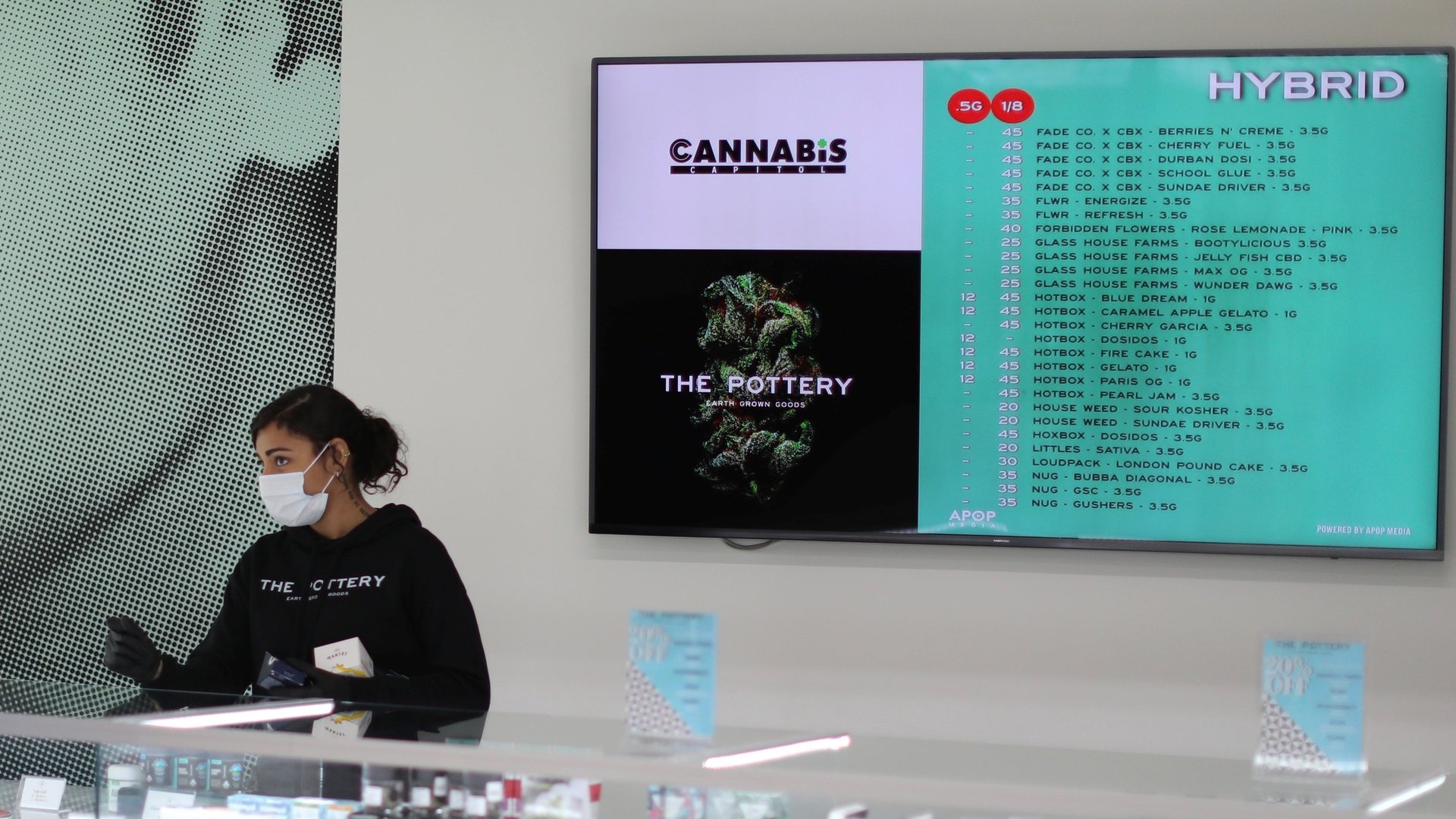

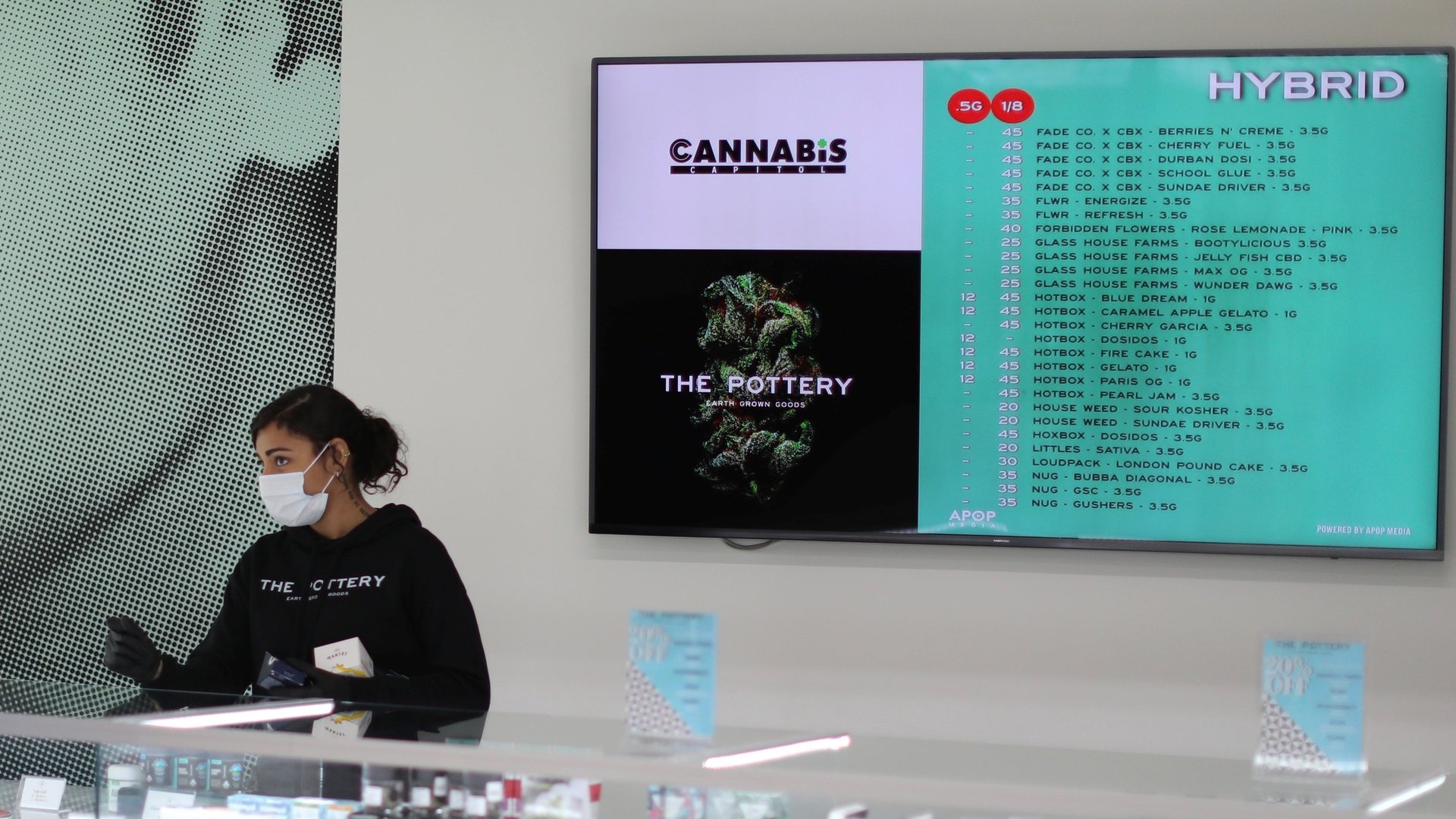

Indeed, in California, where the 420 code was born, marijuana is legal for medical and recreational use. It’s available in dispensaries that sell everything from flowers to candy and baked goods to tinctures and oils and creams, as well as products for pets, all designed to deliver the health and relaxation benefits of this once frowned upon drug. In that state, weed businesses were even deemed essential amid the coronavirus crisis.

After all, if ever there was a time the people needed to just chill, it’s now, when so many of us are under lockdown orders waiting for the world to go back to normal, or whatever that will mean in this era of pandemic. This is perhaps the most universally stressful 4.20 in the nearly half century since the codeword was coined. So by all means, smoke a joint if you’re so inclined. Relax if you can. But keep in mind the sobering fact that the war on marijuana continues.

“It’s barely even slowed down,” Ezekiel Edwards, director of the ACLU’s Criminal Law Reform Project, tells Quartz.

The ongoing arrests for marijuana-related offenses are especially problematic in light of the coronavirus crisis, which shines a new light on the fight to legalize the drug.

Now more than ever, it’s clear that jails and prisons are dangerous places, crime aside. Disease spreads quickly and it’s difficult to maintain hygienic conditions, forget social distancing. That means that today even the most minor offense might result in a death sentence. With the nation in a state of emergency and its crowded jails and prisons scrambling unsuccessfully to keep people safe, it’s high time to halt marijuana prosecutions immediately, the ACLU argues, and legalize weed nationally after the Covid-19 emergency has peaked.

The race card

Edwards says that although marijuana arrests have decreased by 18% since 2010, that downward trend slowed to a halt by the middle of the decade. States still spend tens of millions of dollars each year to enforce marijuana laws, arresting, charging, prosecuting, and putting nonviolent offenders behind bars.

A new report from the ACLU, released today, shows marijuana arrests still clog the American criminal justice system. Between 2010 and 2018, law enforcement made more than 6.1 million marijuana arrests. In 2018, there were almost 700,000 marijuana arrests nationwide, accounting for 43% or all drug arrests.

Notably, race plays a big part in who gets penalized. Marijuana arrests disproportionately affect black people, who are 3.6 times more likely to be arrested for possession than whites, despite having similar usage rates, the ACLU found.

“Marijuana criminalization–from its anti-Mexican roots in the first half of the 20th Century, to its centrality in the War on Drugs, which has been waged selectively in communities of color since the 1970s, to today—has been grounded not in science, or public safety, but in persecuting and targeting specific communities perceived as political, social, and/or economic threats,” Edwards says. “Basically, under the guise of ‘public safety,’ many Americans have been duped into supporting a government that used drug prohibition to turn on segments of its own people.”

The public health perspective

“Drug use, as well as drug abuse, have always been public health issues,” Edwards says. Certainly tobacco and alcohol have been treated as health concerns. Yet when it comes to marijuana, the criminal legal system is employed to address the problem of drug dependence, a health issue it isn’t designed to solve. This endangers everyone—not just those arrested but the law enforcement personnel who interact with them, the people working in jails and prisons, and those who reemerge from these institutions, which are essentially petri dishes, back into a society struggling to flatten the curve of infection.

The US incarcerates more people than any other nation in the world. This was problematic before the pandemic, of course, but now it’s much more difficult to ignore the fact that we are all connected and that everyone is affected by harsh policies that put law enforcement, nonviolent offenders, and entire communities, in danger.

“Never has this been more evident, and the need for reform more urgent, than during the Covid-19 pandemic,” Edwards says. “The criminal legal system is currently faced with a massive public health crisis that demands expedited decarceral action to protect the lives of people incarcerated and those employed by jails and prisons. In addition to the many harms of marijuana arrests unrelated to the pandemic, enforcing marijuana possession laws and other minor offenses predominately in black communities is literally a matter of life and death.”

Every interaction, Edwards notes, from arrest, to searches, to transporting people to police stations or jails, is a danger to the health and well-being of people targeted, the police, and the community at large. The ACLU argues that governors, prosecutors, judges, and other stakeholders across the country must now take bold steps to reduce the number of people in jails and prisons in the short term and start thinking ahead.

“Simply put, state and local governments should refuse to enforce marijuana laws immediately,” Edwards argues, “and when the pandemic subsides, they should make such non-enforcement permanent.”