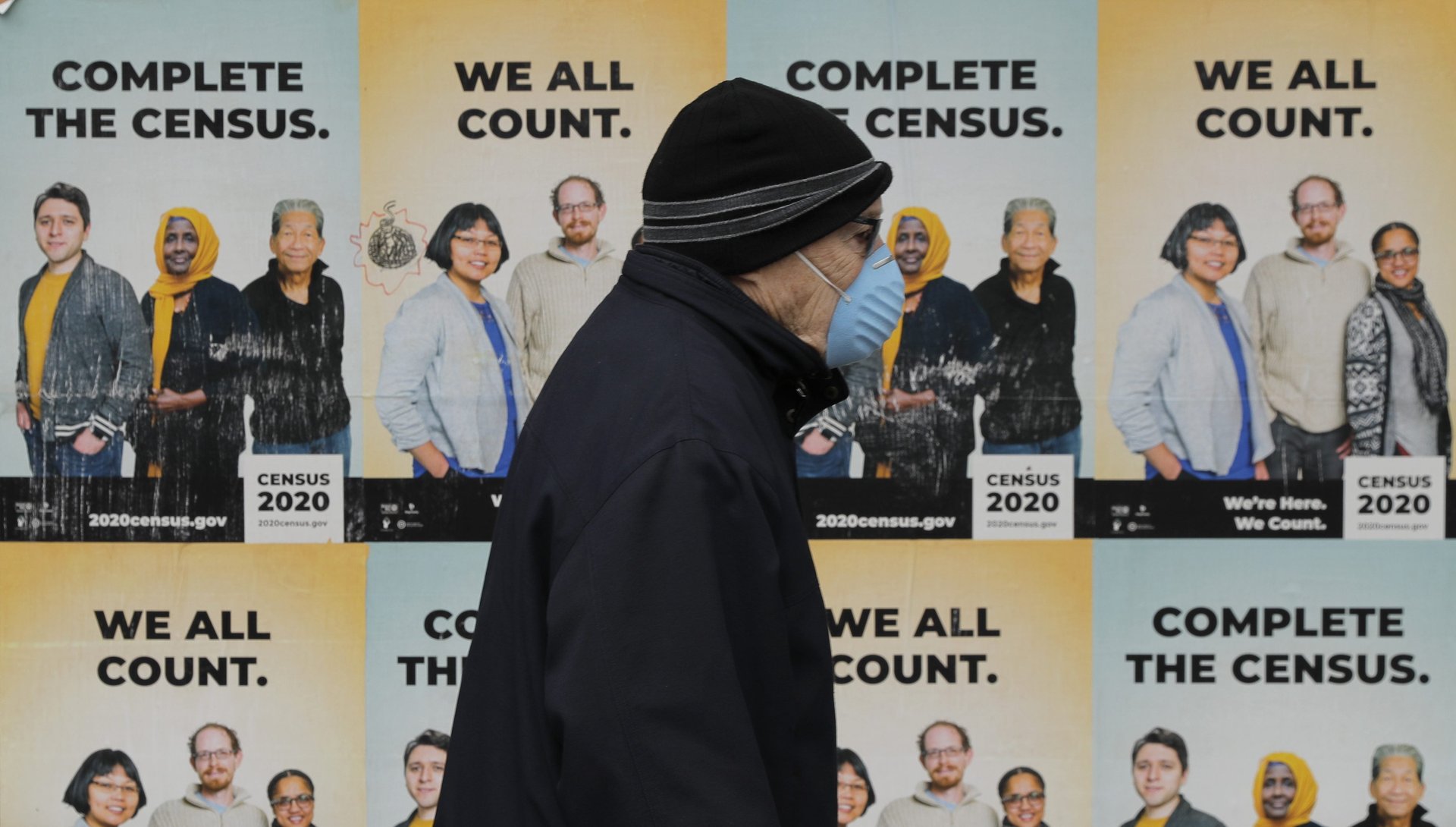

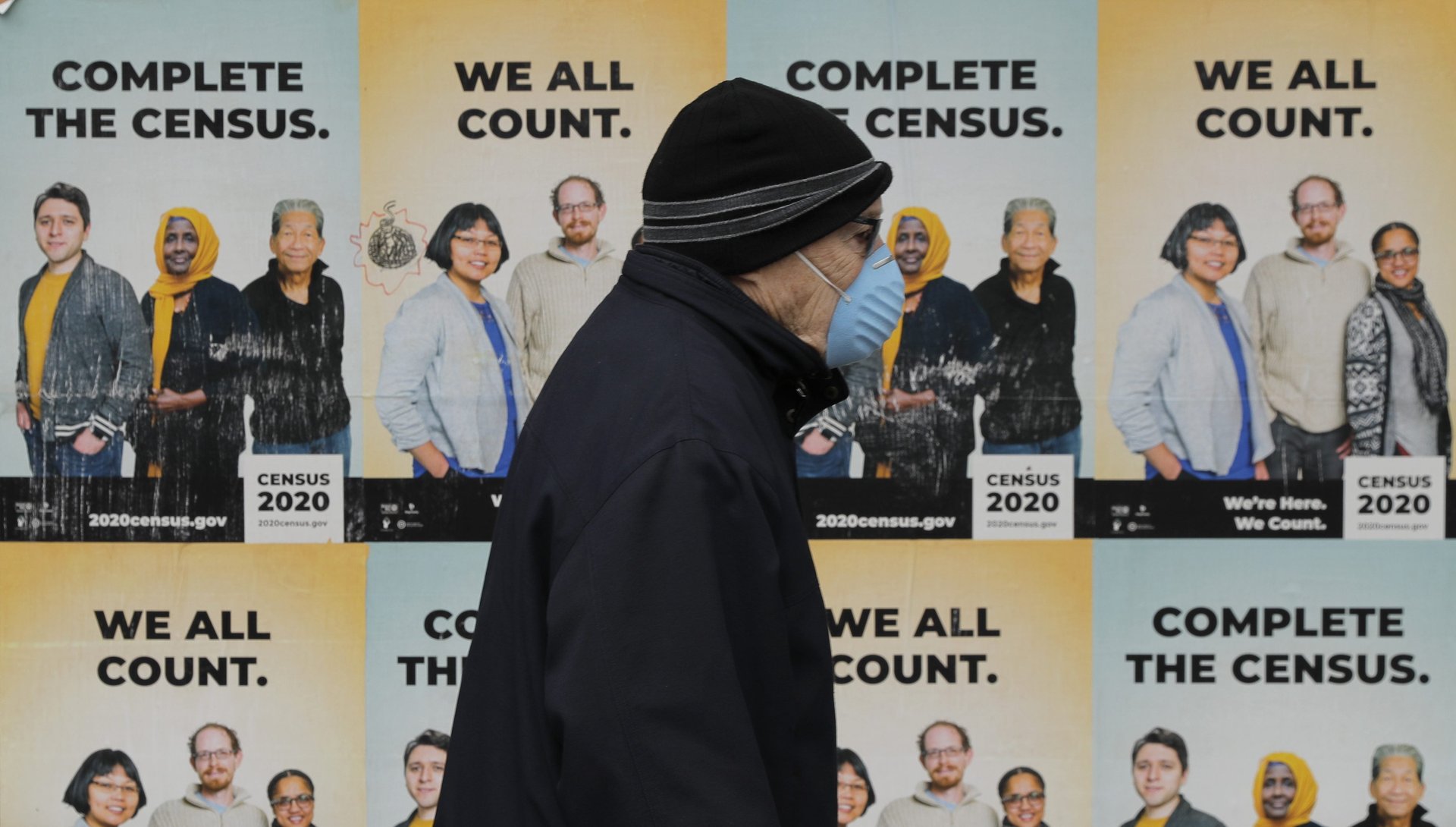

Coronavirus could exacerbate the US census’ undercount of people of color

The 2020 US census was always going to be a tough task, even before the country fell victim to a global pandemic. As coronavirus outbreaks hit minority populations especially hard, experts and advocates worry that these traditionally undercounted populations will fare even worse.

The 2020 US census was always going to be a tough task, even before the country fell victim to a global pandemic. As coronavirus outbreaks hit minority populations especially hard, experts and advocates worry that these traditionally undercounted populations will fare even worse.

US residents have already begun responding to the census. At this point, the self-response rates for counties that have a high number of confirmed Covid-19 cases are no lower than would be predicted by their 2010 response. Still, there are many counties where high numbers of confirmed cases and low response overlap.

Census data determines political representation in the House of Representatives and helps draw congressional districts, but can also influence how many hospital beds, doctors, or pharmacies a community ends up with. Resources for the next pandemic will be determined by how well people are counted during this one.

The coronavirus-census timeline

Census-gathering started on March 12, and on April 20 the self-response rate was 50.5% (the final self-response rate in 2010 was 67%). The 2020 census is the first count where Americans can respond online and over the phone, in addition to the traditional mail-in forms.

The outreach effort ahead of this census has been unprecedented, with numerous organizations helping the US Census Bureau promote the count, said Jeffrey Wice, census and redistricting expert and senior fellow at The New York Law School.

Because of this promotional push, and because so much of the count can happen remotely, this census has some degree of a built-in resistance to a pandemic, as Quartz has previously reported.

After allowing residents to self-respond, there’s always a follow-up period where census workers visit those who haven’t responded in person. Many people get counted that way, particularly marginalized communities that are less likely to be aware of the census. This period was supposed to last from mid-May to the end of July, but the census bureau has postponed the start to Aug. 11, and the in-person count will go through October 31.

In some areas, there is overlap

The chart below shows the relationships between self-response in 2010 and confirmed cases of coronavirus per 100,000 people for US counties, according the New York Times. Higher coronavirus rates do not predict lower response rates, but the data do show that some of the areas with the historically low self-response rates have also been hit hard by coronavirus. For example, Orleans Parish, Louisiana had a 44% response rate in 2010, and has been among the hardest-hit counties in the country.

The counties with the greatest overlap of high coronavirus cases and low self-response tend to be communities with a large share of people of color. There are six counties in the US with 1) 200,000 people, 2) a self-response rates of 60% or lower in 2010, and 3) over 200 confirmed coronavirus cases per 100,000 people. In four of those counties, people of color make up the majority of the population. In the US, about 60% of the population is white and also not Hispanic.

The US Census Bureau didn’t respond to questions for this story.

The many concerns about an undercount

Before the pandemic, the census bureau and local organizers had to confront multiple other obstacles in getting traditionally undercounted communities involved.

“We were sidetracked by the effort to add a citizenship question, which left a chilling effect on a number of people who still think that there is a citizenship question,” said Wice, referring to the Trump administration’s designs to ask people whether they were citizens or not. This instilled fear among undocumented communities that their information would be shared with immigration agencies.

There is also the issue of low trust in government. Communities that have faced discrimination or oppression are hesitant of government requests, and this has led to past undercounts.

The impact of this kind of historical trauma is visible in both low census response rates and high Covid case counts, according to Stephanie Reid, head of Philly Counts 2020, Philadelphia’s census effort.

“You can see that impact in census self-response rates because people don’t want to give their information to government and interact with them; You can see that impact in higher rates of coronavirus in some areas because people don’t trust when government says that you need to practice social distancing.” (In many minority communities social distancing is also simply harder to do because of living or work situations).

Historically there is a strong negative relationship between the share of people of color in a county and self-response rates. An additional 10% share of people of color is associated with a 1% lower self-response rate.

Another fundamental problem is lack of awareness. Census messaging doesn’t reach all communities equally. Internet access in the US is far from universal. Many people just don’t check their mail on a regular basis, or toss the census mailers aside as junk mail. In immigrant communities, people often don’t hear census messaging in their own languages, according to Reid.

The census happens only once every 10 years. “It’s not top of mind even when we’re not in a crisis,” said Anita Banerji of Illinois-based nonprofit Forefront, which does census outreach.

And then, coronavirus came into the mix. Ill people should not be opening doors to anyone, and they might not be able to. Others might be afraid to do so. The census bureau has to consider the safety of its workers. The outreach and education efforts can no longer happen in person and have to be rethought entirely.

“People trust libraries and special efforts were made to focus on libraries as centers for outreach,” said Wice. Now, with library doors closed, people can’t use the library computer or ask a librarian for help.

In the diverse city of Chicago, the overall self-response rate is lower than US average—about 45%. And census data shows that in some poor neighborhoods less than 25% of the population have responded. Those neighborhoods “still need considerable outreach,” said Banerji. Many of the planned efforts were in-person gatherings. People can’t gather in churches, share information during Sunday gatherings.

“You can only do so much to get the word out across communities digitally or via phone There’s just no alternative or replacement for in person contact.”

Why April is key

“The census is supposed to be a snapshot of the population taken on April 1st of the decennial census year,” said Wice. “The census in October doesn’t give you the kind of data that census was meant to look for.”

“The further you get away from April 1st the harder it is to gather accurate data,” Banerji said. People buy new houses, move to different cities, states, or countries, students go to college. Because of the economic crisis, people might have to leave their rentals and move in with family.

August, when the in-person phase of the count is now set to begin, will be during the peak of the presidential campaign.

“Not only are you going to be in a scenario where you’ve got people who might be even more reluctant than we’ve ever seen to answer their door, there’s also going to be more people [knocking] on doors, because of the presidential campaign. And many of these areas where you have historically undercounted communities, higher rates of Covid also are key targets for presidential campaigns,” said Reid.

The fight is still on

Local organizers, cities, and the census bureau are still pushing hard to get the word out. The bureau spent $250,000 on Facebook ads between April 14 and 20. Various local groups are hosting census Zoom parties and presentations. In Illinois, Banerji said, an organization organized a van covered in census posters, blasting music, to get people’s attention out in the real world.

In Philadelphia, the city is combining census outreach with Covid-19 check-ins, calling residents to discuss both, and putting informational flyers in the food it is distributing to the needy.

There is also a chance that though the census might suffer due to the coronavirus, it could also be part of the solution. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention spoke with state governments about using census workers as part of a contact tracing effort, CDC Director Robert Redfield told the Washington Post. If this were to happen, it would make the gargantuan effort that is the decennial census even more heroic.