The future of fitness is at home

Vanessa Packer got out of her boutique fitness studios just in time.

Vanessa Packer got out of her boutique fitness studios just in time.

Packer founded modelFit, a workout designed and branded to do just what it sounds like, in 2014, when boutique fitness was on an upswing. For $40 per class at modelFit’s Soho studio, New Yorkers could strive for long, lean limbs like Karlie Kloss, Chrissy Teigen, or Taylor Swift, all noted modelFit acolytes. By 2016—the same year two of SoulCycle’s founders cashed out for about $90 million a piece—modelFit was opening a second studio in Los Angeles. But in November of last year, Packer, sensing a shift in the fitness economy, let the leases on modelFit’s studios expire.

Meanwhile, 7,000 miles away in central Wuhan, China, a seafood vendor went to the hospital with worsening symptoms from what he initially thought to be a cold. It turned out to be one of the first known cases of the contagious, mysterious illness we now know as Covid-19.

Even before the coronavirus pandemic made crowded classes a relic of the recent past, Packer saw the future of modelFit’s business as digital.

“I could not be more grateful and happy that I made that move when I did,” said Packer, on a phone call from her home in Los Angeles, where she is sheltering in place. “The current state of the world, let alone the fitness industry, is on very uneven ground.”

An estimated 800,000 US workers are employed by 40,000 clubs, studios, and gyms, according to the International Health Racquet & Sportsclub Association (IHRSA). By April 2020, the vast majority had closed, due to stay-at-home orders and the mandated closures of nonessential businesses around the country. Those health clubs served some 70 million Americans in 2017—a number that was likely higher when the pandemic struck.

Globally, over 210,000 facilities served an estimated 183 million members in 2018, raking in about $94 billion in revenues. Now, those revenues have fallen off a cliff, with the IHRSA estimating health clubs are losing a collective $1.23 billion per week of closures.

ClassPass, 2020’s first startup to reach a $1 billion valuation, offers members access to a wide range of fitness classes at private studios for a monthly fee. In early April, the company confirmed it lost 95% of revenue following closures of the vast majority of its 30,000 fitness studio partners in 30 countries, and had laid off or furloughed more than half of an estimated 700 staffers.

Gyms made the cut of phase one of US president Donald Trump’s plan to reopen businesses. But little is certain about what reopening will look like. Members might be wary of visiting a sweaty space filled with shared equipment and hard-breathing patrons, after months of limiting their exposure to a virus known to travel in respiratory droplets. And it’s unclear how long fitness companies will be able to hang on without regular income from membership and classes.

Meanwhile, many of those 183 million gym enthusiasts still want to exercise, and a growing portion of the fitness industry is going online to help them do just that. Some players—from the high-tech home-cycling company Peloton to Instagram influencers to highly adaptable yogis—are particularly well-positioned for the fitness industry’s mass exodus from the gym to the screen. The others may not survive.

Table of contents

It’s getting heated | Wanna free trial? | A speedy transition | It’s all about relationships | It’s a marathon, not a sprint | Why subscribe when you can sweat for free?

It’s getting heated

Before any of us had heard of Covid-19, a growing number of consumers were already working out at home, pedaling on their Pelotons, training in front of their Mirrors, Sweating with Kayla, and doing Yoga with Adriene. All of those providers have seen leaps in engagement over the last four weeks. Now that livestreamed and on-demand workouts are the closest we can get to the gym, the most entrepreneurial and digitally limber players are reaping the benefits.

Well-funded and better established players—ie: those who don’t desperately need your $6 for Zoom yoga class to pay rent—are using the moment to grab customers with free trials.

Meanwhile Packer’s former peers in the studio space—which has become increasingly saturated in recent years—struggle to survive. And they’re arguably more vulnerable to an economic downturn, thanks to their product having been commoditized by ClassPass.

The race for the attention and commitment of home exercisers is on. The stakes have never been higher, nor the competition more fierce. Social media marketing, free trials, and skyrocketing views abound. But will the home fitness winners of the pandemic’s first lap be able to hold their gains for what’s likely to be a marathon?

Peloton in particular stands much to gain—or to lose. The company has hit some rocky patches since its initial public offering in September, not limited to a widely derided viral advertisement that did little to debunk the perception of an elitist company out of touch with the masses. But millions of consumers stuck at home and yearning for exercise are providing a rare opportunity for Peloton—if it can prove to be recession-proof.

“That is by far the biggest question I wrestle with, and investors are wrestling with right now,” said Justin Patterson, an analyst who covers Peloton at investment bank Raymond James. On the one hand, said Patterson, the fitness industry tends to be “fairly resilient” amidst economic downturns. On the other hand, Peloton sells a $2,245 stationary bike, and more than 22 million Americans have applied for unemployment benefits since March.

Hey kid, wanna free trial?

Peloton executives will tell you that a stationary bike is not, in fact, its primary product.

Peloton “is an opportunity to create one of the most important and influential interactive media companies in the world; a media company that changes lives, inspires greatness, and unites people,” wrote CEO John Foley when the company filed for its initial public offering in August last year.

Okay, that’s a lot. But there’s no denying that Peloton’s platform—and home fitness, more broadly—capitalizes on the overlap of several powerful trends, including our collective obsessions with wellness, self-optimization, and social media. Covid-19 has exacerbated those conditions with a captive home audience.

Peloton’s 90-day free trial might be the most aggressive promotion running to attract that audience. No Peloton bike? No problem. There’s a four-week delay on deliveries anyway.

Instead, Peloton is pushing Peloton Digital, an app membership that offers non-cycling on-demand classes including yoga, cardio, and audio running programs with its instructors, who are minor celebrities in their own right. A few weeks ago, I broke a sweat while walking my dog on an on-demand “pop power walk” with Robin Arzón—the company’s wildly popular VP of fitness programming, whose live cycling class attracted some 12,000 home cyclists on March 19.

Peloton’s app promotion appears to be paying off. On March 16, when the company announced the 90-day free trial, Peloton jumped from the 35th-ranked health and fitness app in the Apple store to ninth place—and it remained in the top-10, amongst apps such as Headspace and Calm (for meditation), Flo (for menstrual tracking), and Reflectly (for journaling) for another week.

What started as a companion app for members who had already committed to Peloton’s bike is fast becoming the company’s entry-level drug. “Peloton Digital has become an incredibly powerful lead generation tool for us,” said Foley on a Feb. 5 earnings call—before the app was made free for 90 days—when he discussed attracting more Peloton Digital subscribers by dropping the price from $19.49 to $12.99 per month, and running the app simply to break even. (Peloton’s class subscription for cycling classes is $39 per month.) “We see strong organic conversion from digital subscribers to connected fitness product owners as digital members fall in love with the classes, the instructors, and the community … Our goal is to make Peloton Digital available on every screen in your hand and in your home.”

A speedy transition

For many gym and studio operators, last month’s transition to home fitness was whiplash-inducing. Even Peloton struggled with the shift, with instructors continuing to offer live online classes from its Manhattan studio without in-house cyclists—to much controversy and conversation on the many Peloton group Facebook pages—until April 6, well after New York governor Andrew Cuomo issued a stay-at-home order March 22. They only closed after a studio employee contracted Covid-19.

When I emailed Meredith Poppler, the communications head for the International Health Racquet & Sportsclub Association, she apologized for a delayed reply: “As I spend all my time trying to save the industry, I find I don’t have the time to talk about the industry that desperately needs saving.” (The IHRSA was later credited for helping to lobby for gyms’ inclusion in the first phase of businesses to reopen in the US.) Poppler estimated clubs forced to close in the US were bleeding a collective $620 million in revenue per week. “Some clubs are streaming fitness classes,” she wrote, “but in most cases, that is at a cost of keeping members engaged, rather than a revenue generator.”

Packer, on the other hand, was well-poised for the move.

Her modelFit business started offering virtual training via FaceTime in 2015, after clients requested workouts they could do while traveling. Meanwhile, Instagram allowed modelFit to engage its followers’ attention (and glutes), with videos of its excruciating lifts, squeezes, and slides. Packer said those developments proved to her that fans were not merely willing to work out with their phones or laptops instead of a real person—they valued it.

“You don’t have to worry about someone else seeing you, or tuning in at a certain time,” said Packer of the appeal, which extends beyond mere convenience for those less comfortable in live group settings. “You could have your hair in whatever mess it is, and wear whatever you want and be able to still do the workout.” (This is no small asset, for any non-model who has witnessed the caliber of coordinated spandex in a modelFit studio.)

So in 2017, Packer’s team began to build a library of videos available to subscribers for $19.99 per month—about 5% of the cost of a modelFit unlimited monthly studio membership, which then ran a gut-punching $425. ModelFit would release two new videos per week on its website, which it promoted with email blasts to its growing list of subscribers.

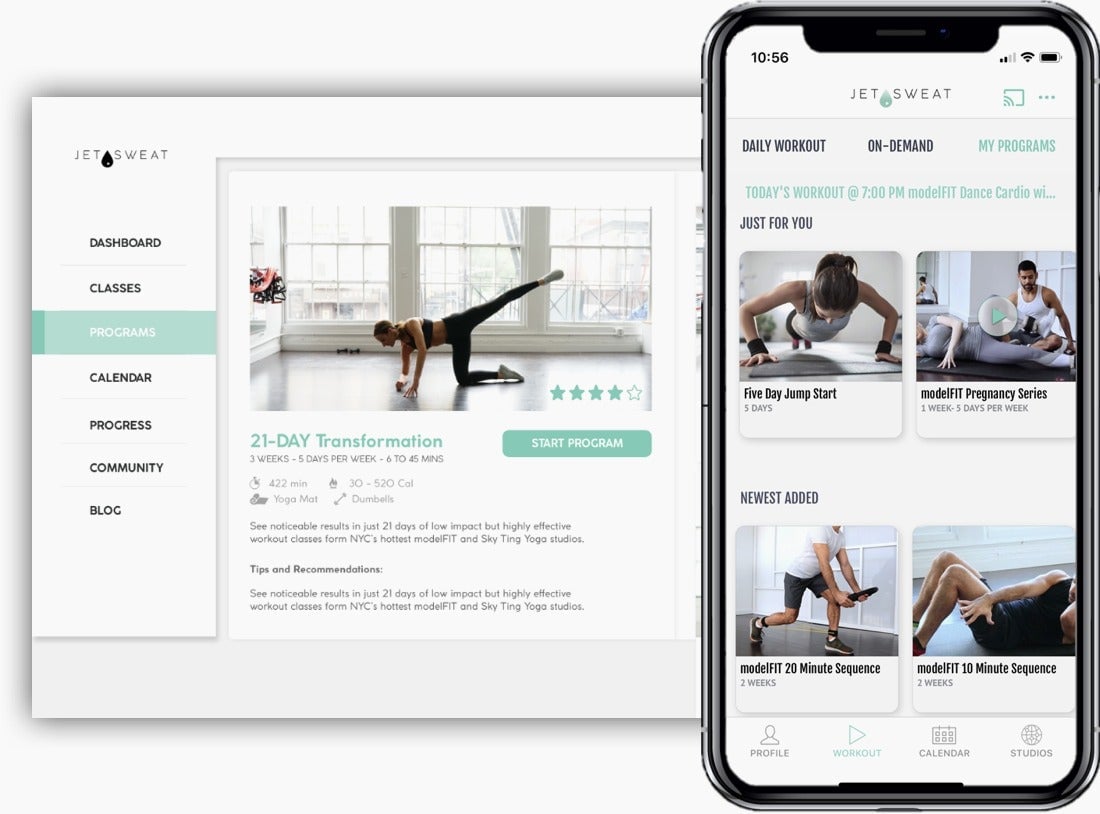

Packer built modelFit’s digital business steadily, and then, shortly after modelFit’s studio leases expired in November, she sold it to JetSweat—a New York-based web platform and iOS app that provides subscribers with on-demand video workouts from high-end boutique studios around the world. JetSweat acquired modelFit’s catalog, users, data, and Packer joined the company—which also has exclusive streaming deals with brand-name studios including Sky Ting Yoga, WillyB Crossfit, and The Dailey Method—as a consultant in January.

Her new employer has spent the last month on overdrive.

“It’s insane,” said JetSweat co-founder Erin Frankel, adding that the company more than doubled both monthly revenue and subscribers. “We’re doing incredibly well right now. We’ve been experiencing a ton of demand both from on the consumer side and from studio partners.”

“We were shooting content 20 hours a day,” she said of the week leading up to stay-at-home orders in New York in California. “With our team, we went from one studio to the next and we were signing so many new studio partners we didn’t even have time to shoot with all of them. We hired a team in San Francisco, a team in LA, and were already interviewing teams in Houston and Atlanta and London—and then the whole world went on lockdown.”

Now, JetSweat is producing and uploading those videos for the whole world that’s on lockdown. For those at home, the platform offers everything from one-minute deadlift tutorials to hour-plus yoga and meditation sessions. For studios, which sign on for two-year exclusive contracts, it represents access to a growing audience and a share of JetSweat’s monthly earnings. Usually, partners would pay $1,000 upfront for Jetsweat’s filming and production fees, but the company has waived it given recent circumstances.

“Studios can’t afford it,” said Frankel, adding that each one is now bringing so many customers that video production pays for itself. “We’re tripling the number of subscribers we’re typically getting from each studio.”

JetSweat is also launching a white-label service to let clubs host videos on their own website—“a turnkey solution for them to go digital,” said Frankel. The company accelerated the initiative by 18 months to get the first white-label partner, the Manhattan-based Yoga Vida, up and running that week.

Even those without deep digital resources have benefitted from getting online, and fast.

“I’d never taught a class online before. Most of us hadn’t,” said Sian Fujikawa, the cofounder of Love Yoga in Los Angeles. Love’s revenue is usually made up of a combination of teacher trainings, yoga retreats, and classes that fill its studios in Venice Beach and Echo Park with 50 students, mat-to-mat. “Now none of that exists, and we’re trying to survive this by teaching classes on Zoom, like everyone else.”

The emotional process of putting the studio online, Fujikawa said, was hard. But her manager said the logistics of getting Zoom classes onto a signup page—where Love charges students six dollars instead of its usual $24 for a drop-in class—were easy. Those Zoom classes, Fujikawa found, “turned out to be kind of a cool thing.”

It’s all about relationships

Love has had as many as 400 students join Zoom classes (the studio occasionally offers free sessions sponsored by like-minded lifestyle brands—think CBD, pour-over coffee, and seaweed-based skincare), and Fujikawa said the live exchange of Zoom lets the studio maintain a strong sense of community, and expand it.

“We get to see our students all the time, and I can say, ‘Jane step your right foot forward a little bit more, bend your knee,’” said Fujikawa. “But the other amazing thing about it is seeing students that I haven’t seen in 10 years, or my friends from middle school that I haven’t seen in 25 years—um, that’s not true, it’s more like 30—but it’s kind of beautiful to connect in a way that wasn’t possible before. And also to meet students that live in Paris and Russia.”

Many of those far-flung students likely know Love Yoga from its Instagram account, which has some 22,000 followers (in addition to a collective 21,000 between Fujikawa and her cofounder Kyle Miller). Even if the stay-at-home orders were to lift tomorrow, Fujikawa says Love Yoga’s business model is likely to be forever changed.

“The Zoom classes actually seem to be pretty popular and they do give us the ability to teach a much broader audience. So I think there’s a world in which we’ll keep doing this or something like this going forward—which is great, because we wouldn’t have done it otherwise,” said Fujikawa.

“Our little world was working the way it was. Now that we’ve been forced to shift, I think that shift has actually been expansive for us.”

Cultivating connections with that expanded universe of fans will be imperative to survival for businesses big and small.

Kayla Itsines, the personality behind Sweat with Kayla, has a staggering 12.4 million Instagram followers, and has been regularly posting videos of them sweating through their workouts. “We are very, very focused on genuinely committing to building relationships with our followers,” said Tobi Pearce, CEO and cofounder of Sweat, and Itsines’ fiancé. “We take every opportunity that we can get to make sure that we further that relationship with them.”

Pearce said they saw the writing on the wall when the coronavirus was spreading in Italy. They fast-tracked three new #SWEATathome workout programs, and offered a free month for new app subscribers—an acknowledgement that many users wouldn’t have access to equipment or spacious environs, or might struggle to pay the usual $19.99 per month for a subscription. Pearce said use of home workouts had tripled on the app since the previous month, and new users were quicker to complete their first workouts after registration—usually a hurdle to adopting a new habit, he said.

It’s a marathon, not a sprint

While influencers like Itsines and Peloton’s star instructors take to social media to further relationships with followers, teachers worldwide are hustling to bring their real-life communities online. For many businesses, it’s sign on or close down.

Even Fujikawa, for all her sunny disposition, said Love Yoga’s financial outlook is “bleak, to be honest.” Since we spoke, she said via text that the company’s small business loan application had been denied: “Not enough to go around.” In March, Fritz Lanman, CEO of ClassPass, posted a petition on Change.org signed by executives from dozens of other global fitness companies asking health and finance ministers for relief in the form of rent relief, stipends for staff, and debt postponements.

In the meantime, ClassPass announced it would offer live-streamed classes to app subscribers, and pay studios 100% of the proceeds.

“We did have ClassPass, and we are still doing that,” said Fujikawa. “The interesting thing is that no one’s using it.” Instead, virtual students are signing up directly through the studio’s website.

“What’s going to sustain yoga teachers and instructors is the relationships they have built in the past,” said Johanna Quintero, who spent the last decade building a career that until recently involved teaching yoga at two Los Angeles studios, training private clients, and guiding yoga, meditation, and sound therapy at an addiction recovery center. “If that was a strong pillar, then there’s hope.”

Now, Quintero is teaching on Zoom and offering sound baths on Instagram Live, bringing in an estimated 15% of her regular income—a rate at which she estimates she can continue to pay rent for about three months. But like Fujikawa, Quintero said the intense circumstances of Covid-19 and quarantine make for a palpable sense of connection online. But of course, connection alone can’t pay the bills.

“For the first three months I’ll be okay,” said Quintero. “But I don’t know after that … Let’s go with the basic needs: Rent, food, utilities, shelter. We live in one of the most expensive cities in the world.”

Why subscribe when you can sweat for free

Of course fitness instructors aren’t alone in losing income. With millions of Americans out of work, it’s no surprise instructors offering free classes—whether on YouTube, Instagram, or Zoom—are seeing huge traffic.

If the pandemic’s Instagram home fitness circuit has a breakout star, it is most certainly the short-shorted and generously mustachioed choreographer Ryan Heffington, who owns the Los Angeles dance studio The Sweat Spot. With his lo-fi, high-energy Instagram Live “SweatFests,” Heffington has started a free party to which he handily welcomes several thousand people five times per week. My 74-year-old mother, Fleabag’s hot priest Andrew Scott, Reese Witherspoon, and the pop star Pink—who made a virtual guest appearance—have all endorsed this workout within the last few weeks.

Even Packer, who is admittedly partial to modelFit and JetSweat, is under his spell.

“I love him,” she said, when we spoke on a recent Tuesday. “The ability to connect! There were 4,500 people dancing this morning. I mean that’s unbelievable. You feel that energy! I think that is the best example of such a valuable, quality free live experience that is really hard to compete with.”

For Heffington, whose choreography for artists such as Sia and Spike Jonze had already made him famous in the arts, the Instagram Sweatfests have brought a stronger spotlight to his dance studio, for which he is accepting donations via Venmo. (The most I have paid for any fitness class or subscription in this pandemic was the $25 I was moved to donate after my first Sweatfest.)

YouTube, as well, offers a veritable smorgasbord of free home workout videos, of which average daily views have increased by over 200% since March 15, according to a YouTube spokesperson. The payment rates YouTubers earn per 1,000 views vary widely, as do their endorsement deals and side hustles, but many have seen views skyrocket in recent weeks.

YouTube reports six of the top-20 livestreams in 2020 belonged to the “PE with Joe” series that British “Body Coach” Joe Wicks started for kids on March 23. Wicks promised to donate his earnings from the series to Britain’s National Health Service, and on April 20 announced he had £91,250 ($112,100) to give. The series has also reportedly earned Wicks a six-figure book deal, along with many, many followers. In February of this year, Wicks’ YouTube channel, which generally traffics in short high-intensity interval training (also known as HIIT) videos for grown-ups, had about 14,000 subscribers, according to the social media tracker Social Blade. Now, he has 2.28 million.

That’s still a fraction of the 7 million subscribers Adriene Mishler of Yoga with Adriene, has won with her easygoing approach to yoga for back pain, bedtime, and text neck. In March of 2020, YouTube videos from the Austin, Texas-based Mishler were viewed some 29 million times—nearly triple the views of March of the previous year.

No matter how hard subscription-based companies hustle for followers’ attention and affection throughout the pandemic, the specter of free videos—on YouTube and beyond—looms large. I’ve registered for several free trials of subscription services in recent weeks, and have so far remained noncommittal. But I tell anyone who will listen about Heffington’s Sweatfests, or my system for blasting my own Spotify playlist while doing a mercifully music-free Fitness Blender cardio video. (Likely because of licensing issues, the music on some paid fitness content can be abysmal.)

Perhaps Jetsweat—or even Peloton—will eventually look more like websites like Fitness Blender or DoYogaWithMe, where at least a sampling of videos will be offered online for free, in hopes of enticing users beyond a free trial period. And if JetSweat’s white-label video player catches on, the company can help businesses produce and host that content.

Patterson, the Peloton analyst, said personalization is one key to giving paid content an edge. He referenced Peloton’s ability to use technology to create “targeted, structured” programs to help members train for specific goals, and the “social community” aspect of Peloton’s leaderboard, where stationary bike-owners can communicate and observe how they compare to others in a live class, in real-time.

But channels like Yoga with Adriene prove it’s possible—even in the vast universe of YouTube—for fans to find free fitness content that makes them feel not only healthy and strong, but connected and understood.

In her first post-pandemic video, “Yoga for Vulnerability,” Mishler opens by gently guiding viewers to lengthen their lower backs in the fetal position on a folded blanket. Her Australian cattle dog Benji lays beneath the window behind her.

“Here we are. Man, we’re doing it,” says Mishler. “Close your eyes, take a deep breath in. And as you exhale, my darling friend, just start to notice. Notice how you feel.” After 32 minutes of stretching and resting, Mishler ends the practice with a self-embrace while laying on her back: “You might be like, ‘Oh man, Adriene. This was so good until you asked me to hug myself,” she says, with characteristic self-deprecation. “But just give it a go. See what happens.”

In more than 1,500 comments, viewers leave some indications of what happened. Many involve tears, gratitude, and feeling that the class was designed for them.

“’I’m starting to think Adriene is psychic,” wrote one. “Because this practice was just what I needed.”