US businesses want immunity from coronavirus lawsuits

Say you’ve been home alone, have no contact with others for weeks, and are called back into your office, where you promptly fall ill, having been infected by coronavirus. Now your life and livelihood are on the line. What do you do?

Say you’ve been home alone, have no contact with others for weeks, and are called back into your office, where you promptly fall ill, having been infected by coronavirus. Now your life and livelihood are on the line. What do you do?

Normally, you might sue and recover damages for lost wages, medical expenses, and your pain and suffering—if you can prove that your employer’s negligence, recklessness, or willful disregard for a safe work environment caused your illness.

But these are not normal times, which is why US businesses—represented by the Chamber of Commerce—are lobbying Congress for immunity from liability lawsuits related to Covid-19. Similarly, in a letter to lawmakers this month, 20 conservative advocacy groups, including Americans for Prosperity, asked the federal government to “create shields from trial lawyers’ frivolous, costly, and job-killing litigation schemes.”

Companies do not want to be held responsible for possible illness, death, lost wages, or other disruptions after government lockdowns are lifted.

“Unchecked litigation for any injury linked to the coronavirus would significantly increase uncertainty—for small businesses, nonprofits, corporations, universities, transit systems, shopping malls and retirement villages,” writes Evan Greenberg, CEO of Chubb Insurance, in a Wall Street Journal opinion piece entitled “What Won’t Cure Corona: Lawsuits.”

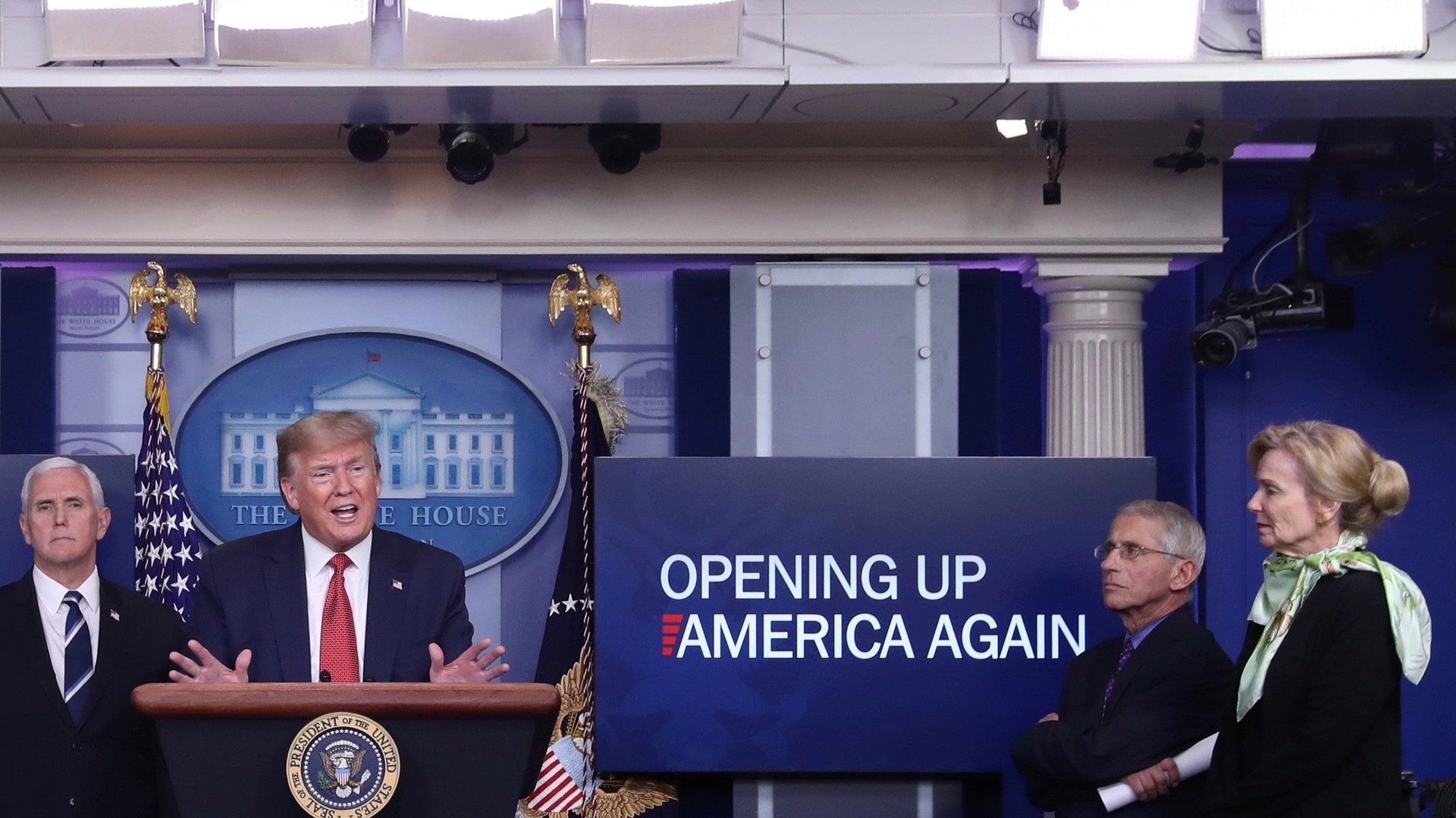

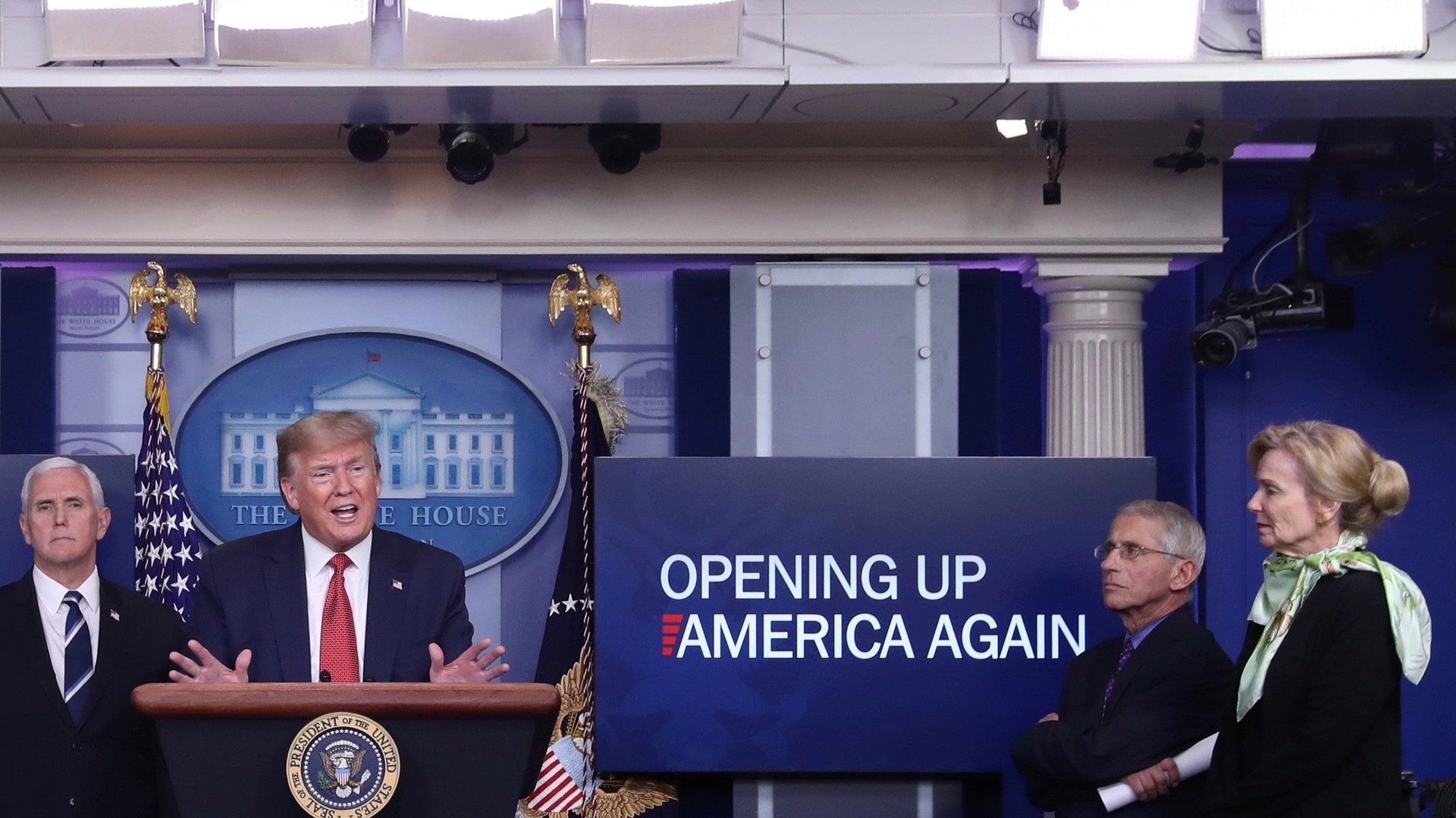

This view has also been articulated by Trump administration officials like White House economic advisor Larry Kudlow, who told CNBC this week, “You’ve got to give the businesses some confidence here that if something happens, and it may not be their fault—the disease is an infectious disease—if something happens, you can’t take them out of business. You can’t throw big lawsuits at them.”

This resistance to liability isn’t new. Tort law—which is derived from the French word for wrong—is the civil justice system mechanism for holding companies accountable for injuries caused by their negligence, recklessness, or willful misconduct. Tort reform is the idea that this mode is too punitive and costly, and it’s been a hot topic since the 1970s. Reform efforts, spearheaded by insurers and corporations, have led to caps on damages in many states.

But in 2020, amid the pandemic, talk of limited liability is gaining new ground even as more employees face graver risks than ever before at work. If a government—state or federal or local—says businesses can reopen, that alone won’t shield those who resume operations from lawsuits. In order to have immunity, authorities would have to pass legislation explicitly exempting coronavirus claims from the universe of negligence litigation.

“Businesses are scared,” University of Michigan economics and public policy professor Justin Wolfers tells Quartz. And that’s just as it should be. Limiting liability is bad economic and public policy, he argues, because it enables dangerous behavior. “We want businesses to be scared. The claim from the Chamber of Commerce that liability will make people scared to do business is correct and that’s the point.”

Wolfers likens liability lawsuits to a kind of tax on bad actors—individuals or companies whose negligence damages people and society. If there is no economic risk to failing to safeguard workers, there is little financial incentive to protect employees. “We want businesses to take responsibility. All of tort law is about creating a strong incentive for people and companies to not act badly,” Wolfers says.

Negative externalities

To understand the economist’s perspective, let’s consider “externalities.” In economics, an externality is a cost or benefit associated with an action, which accrues to a third party, not the primary actor.

For example, a business that pollutes creates a negative externality that costs its community and society. There are mechanisms to account for that, like carbon taxes, which force companies to pay for the harms others experience from their for-profit activities. Another negative externality of corporate behavior, this one addressed in part with lawsuits, is the American opioid crisis. States have sued major drugmakers, like Purdue Pharma, for pushing highly addictive prescription pain medications such as OxyContin despite knowing the dangers.

In the context of the pandemic, infection is one obvious negative externality. If you go back to work and are infected and fall ill because your employer hasn’t taken sufficient precautions to ensure a safe environment—doing nothing differently than it did before the pandemic, say—your illness is a negative externality of the business’s desire to resume operations without making concessions to the new circumstances, which require greater vigilance, additional protocols, and a new approach.

As Wolfers puts it, a negative externality is a fancy economic term for “selfish” behavior. “You want people to be able to sue. Because you want people to be liable for the damage they do if they aren’t acting responsibly,” Wolfers explains.

While he concedes that there are problems with potential coronavirus liability lawsuits, Wolfers says companies shouldn’t be immune. It’s true that juries do sometimes award astronomical damages to plaintiffs and that litigation costs are high, even for a defendant who ultimately isn’t proven guilty. And it may well be that negligence will be hard to prove. Still, Wolfers argues these are not reasons to eliminate liability, which is meant to protect people. “What’s crystal clear is that if you let employers off the hook, they won’t take safety precautions.”

Tortious conduct

As it stands, immunity from liability aside, corporations go a long way to shield themselves from losses caused by their wrongdoing.

Georgetown University Law Center professor Robert Thompson specializes in corporate law and limited liability, examining the structures companies use to protect valuable assets. He tells Quartz that major corporations operate through hundreds of subsidiaries in order to ensure that a parent company won’t experience losses when a subsidiary that pollutes and is sued, for example, has to cough up damages.

But coronavirus is a new liability that corporations haven’t planned for in advance. The lobbying efforts for limiting liability would protect companies as they look for new ways to shield themselves from losses in a novel situation. “Companies are worried about their usual toolbox,” Thompson says. “This new thing has popped up and it doesn’t fit their planning.”

Traditionally, companies use two primary means of limiting liability. Apart from trying to “cabin claims,” limiting damages to specific subsidiaries, they defend against negligence suits vigorously, arguing that they didn’t cause the alleged harms. Torts law isn’t based on strict liability—harm alone won’t result in a damage award. Plaintiffs have to show some kind of misconduct on the part of the companies, whether it’s a failure to take precautionary measures, reckless indifference to risk, or willful bad acting. If, however, companies are granted immunity from liability lawsuits through legislation or new regulatory guidelines, they won’t even have to defend themselves.

In the context of the pandemic, proving negligence will be difficult, Thompson believes. Still, he says, “Blanket immunity seems to be an overreach. We use negligence suits because we want bumper guards on actors who make decisions that aren’t justifiable, those who don’t exercise ordinary care.”

The law professor concedes that we are living in “weird times.” However, legislation that would protect businesses from negligence suits—giving them a kind of certainty they no doubt desire in an uncertain world—exposes workers and society at large to risk and threatens to erode modes of protection relied upon for centuries.

Risky business

Ultimately, businesses will have to weigh the risks of opening for themselves, limited liability or no. A company that ends up associated with infection and death isn’t likely to flourish whether or not it’s shielded from negligence lawsuits. They are aware of the dangers.

Colin Kopel of the Goliath Consulting Group—a restaurant adviser based in Norcross, Georgia—says that none of its local clients are opening up their dining rooms although the state government is lifting restrictions. Goliath has not yet discussed liability risks with lawyers or insurers, Kopel says, because it’s primarily concerned with guidelines from federal and state agencies on the appropriate health measures to take to ensure worker and customer safety.

“Operating a restaurant means navigating through multiple layers and areas of liability,” Kopel tells Quartz. “Providing a service to the public comes with the assumed level of risk. Adding food and alcohol to the equation means additional training, education and vigilance on behalf of ownership, management and staff.”

The pandemic piles on additional concerns. Workers will need specialized training and equipment. Businesses will have to be vigilant about following new standards that aren’t even set yet. From Kopel’s perspective, liability for negligence arising from the pandemic is just one of many elements that must be considered in this new, difficult business environment, and not necessarily the primary concern.

“While any government support on infection liability would be appreciated, safe procedures and recommendations from the CDC and other public health experts will dictate when we open our dining rooms,” he says. “Without the ability to protect our staff, guests, and community, limiting legal liability cannot ethically or responsibly factor into our decision to open to the public.”

Max Lockie contributed reporting from Georgia.