After returning home to Shanghai from a work trip in mid-February, 37-year-old finance executive Yuling began observing flu-like symptoms and immediately quarantined herself at home. Yuling lives alone and is a self-proclaimed “sheng nü,” the colloquial Chinese term used to describe an unmarried woman over the age of 27, which roughly translates into “leftover woman.”

To avoid any further transmission of the virus, she declined any help from her family, relatives, or friends. Her day-to-day support system took the form of delivery services for food and supplies. “They would come and leave everything I’ve ordered outside. I then waited for the delivery boy to leave before grabbing them,” she said.

During our most recent phone call, Yuling reflected, “I really wished I had a partner when I was dealing with all this; 2020 is the year when I am supposed to date ‘intentionally.’” The coronavirus outbreak created a significant obstacle to her progress. “I am not getting any younger, and I want a family,” she stressed, “but more importantly, my family is desperate to marry me out.”

New questions

I met Yuling in Shanghai last summer while collecting data for my doctoral dissertation, which examines online dating in densely populated cities such as Shanghai and New York. The rapid spread of the coronavirus has introduced yet another layer of complexity to my work. Among other things, it has prompted me to ask: What does seeking love look like in extraordinary times? And how does romance adapt during a pandemic?

Documenting the stories and intimate pursuits of singles living at the epicenters of one of the biggest viral outbreaks in recent memory reminds people that even during tumultuous times, life goes on. And so does the pursuit of partnership and romance. For people whose lives have been upended by an evolving crisis, maintaining some semblance of normalcy can be an important coping mechanism.

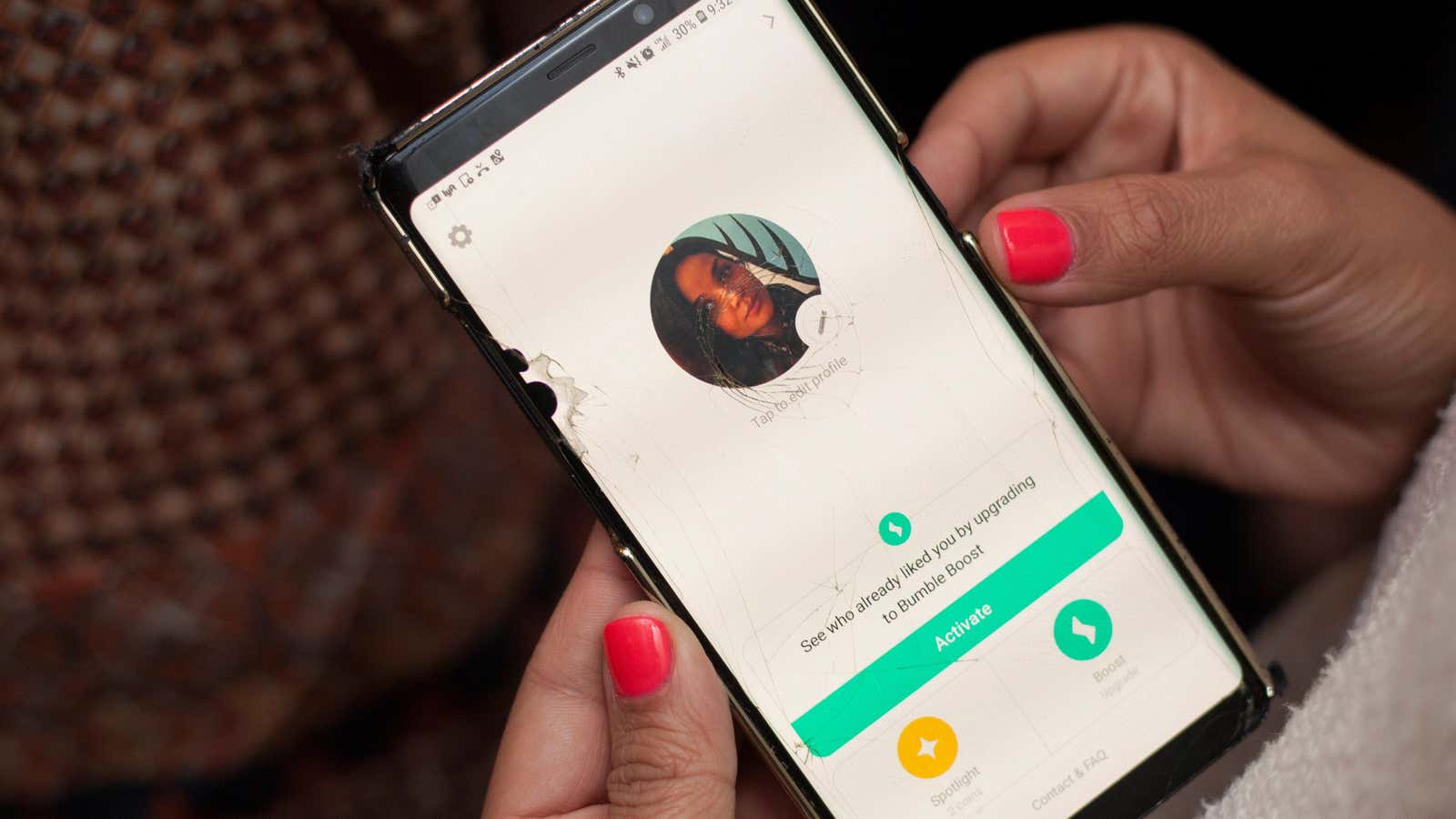

Due to her busy work schedule and itinerant lifestyle, Yuling—like many people these days—mostly relies on dating apps to meet potential partners. “The funny thing is, before I went on this work trip, I had been going out with this guy that I saw great potential in. But right after he learned about my symptoms, he disappeared on me. A few days later, he blocked me on WeChat.”

Your country, your matchmaker

Yuling and her family are not the only ones worried about her singlehood; their anxiety is also shared by the communist state. China is currently experiencing a precipitous population decline, much of it attributed to the cultural ramifications of the now defunct one-child policy. Deeply concerned with its slow population growth and aging demographic, the country’s persistent gender skew (a reported 115 males for every 100 females) adds some unique problems that plague an already highly competitive singles market. If these trends continue, the social and economic shifts that are currently looming in the shadows will surely impact the country for decades to come.

The Chinese state has been taking matters into its own hands by organizing frequent matchmaking events for its young party members and strategically deploying state media and policy amendments to “talk its people into marriage and out of divorce.” Although the state has the ability to easily leverage the online dating industry to implement its population directives, it has largely taken a critical stance on dating apps. To the party, these apps are a hotbed for “negative information” and a breeding ground for undesirable social values.

Quarantine love

Meanwhile, Yuling sensed her symptoms worsening. She admitted herself to a local hospital a few days after she began her self-quarantine. She was tested and found positive for Covid-19 but recovered relatively quickly with the care she received. “While receiving treatment at the hospital, I was on my phone a lot,” she said. Which also meant she spent a considerable amount of her time swiping on dating apps. “Aside from religiously browsing WeChat for news and updates, and updating my family about my condition, the one thing I did the most was browse dating profiles and talk to my matches from Momo,” which is one of China’s most popular dating apps.

“It was an escape for me,” she said. “I needed something I could look forward to when all of this ended.”

Yuling’s experience surfaces an unexpected benefit of tech-mediated romance—the ability to facilitate connections even at times when people actively avoided traditional dating hotspots like bars and restaurants. “It was the one bit of fun and optimism I needed,” she said.

Unlikely bedfellows

Unbeknownst to many, after the National Health and Family Planning Commission—an agency put in place to reverse China’s slow population growth—dissolved in 2018, its main functions were absorbed by a new council called the National Health Commission, which is incidentally also the department coordinating national efforts at mitigating the spread of Covid-19. In other words, the agency responsible for China’s population problem now works a double shift—one to foster a milieu conducive to forming relationships, one to reduce Covid-19-related mortality. That finding love and avoiding fatal disease have become unlikely bedfellows under common management is perhaps not coincidental.

After a week of rest at home following her discharge, Yuling decided it was time to go on a date with someone she had matched with while she was hospitalized. The day of, she picked out an outfit she felt confident in—an ensemble that kept her warm while concomitantly accentuating her personal style. Even though she had to don a face mask, she decided to put on her usual face of full makeup.

She met her date on a Thursday afternoon at a public square near the city center, a place both parties had agreed would be safe. They greeted each other while standing a meter apart. They both wore gloves, but did not attempt a handshake.

Yuling recalled the experience to be rather uncomfortable initially. “I took off my mask so that he could see what I looked like. And then he did the same, but just for a split second. I was able to steal a glance before he put his mask back on. He looked just like his photos, which is always a pleasant surprise in today’s world.”

The two found a bench nearby, sat on opposite ends, and took turns inquiring about each other’s lives. They talked about their respective childhoods, jobs, families, and dreams. The date lasted just under two hours. It felt like any other date. To Yuling’s surprise, when she disclosed that she had just recovered from the coronavirus, her date reacted with remarkable calm, quipping that she was “probably the safest person in Shanghai to be around.”

Sensing some positive energy emanating from her voice over the phone, I asked Yuling if she would see her date again. She paused for a few seconds and said, “It was sweet of him to come out during such an unsettling time. He was handsome, accomplished, and showed interest even after learning about me contracting the virus.”

I repeated my question. “So you will see him again?” She answered, “No, he was too short, and my mother wouldn’t have approved. I am very much still looking. In fact, I have another date this weekend.”