The US Supreme Court desperately seeks a “limiting principle” in Trump tax cases

The US Supreme Court heard oral arguments today in cases about subpoenas seeking president Donald Trump’s taxes and financial records from his accountants and bankers. The matters have been long anticipated, are hotly debated, and will surely be discussed and dissected for years to come.

The US Supreme Court heard oral arguments today in cases about subpoenas seeking president Donald Trump’s taxes and financial records from his accountants and bankers. The matters have been long anticipated, are hotly debated, and will surely be discussed and dissected for years to come.

Because, as Trump’s counsel continually emphasized at the hearing, this isn’t just a fight about this president’s records. It’s a battle between branches of government— a duel between Congress and the chief executive with the supreme jurists deciding the winner.

Congress says it has the authority to subpoena the records because it needs the information for possible future legislation. The president claims that the House committee investigations that led to these requests are politically-motivated and serve no legitimate legislative purpose—they are only designed to undermine the president and harass him.

The first two cases the court heard today involved those congressional oversight committee subpoenas to Trump’ accountants, Mazars USA, and Trump’s bankers, Deutsche Bank and Capital One. The committees say they need the records in order to study conflicts of interest, possible money-laundering by Trump family businesses, foreign meddling in presidential elections, and disclosure rules. They may draft new legislation as a result of what these investigations show them about the president and his associates’ activities, the committees argue.

But no one has seen any of these papers yet because the president intervened in the cases. Lower courts have so far ruled against him, finding no problem with the subpoenas. The high court must decide if those tribunals were right.

Authority issues

“The subpoenas at issue here are unprecedented in every sense. Before these cases, no committee of Congress tried to compel such a broad swath of the president’s personal papers,” Trump’s counsel Patrick Strawbridge complained. He accused the congressional committees of broad overreach and suggested that the House of Representatives had no authority to issue the subpoenas.

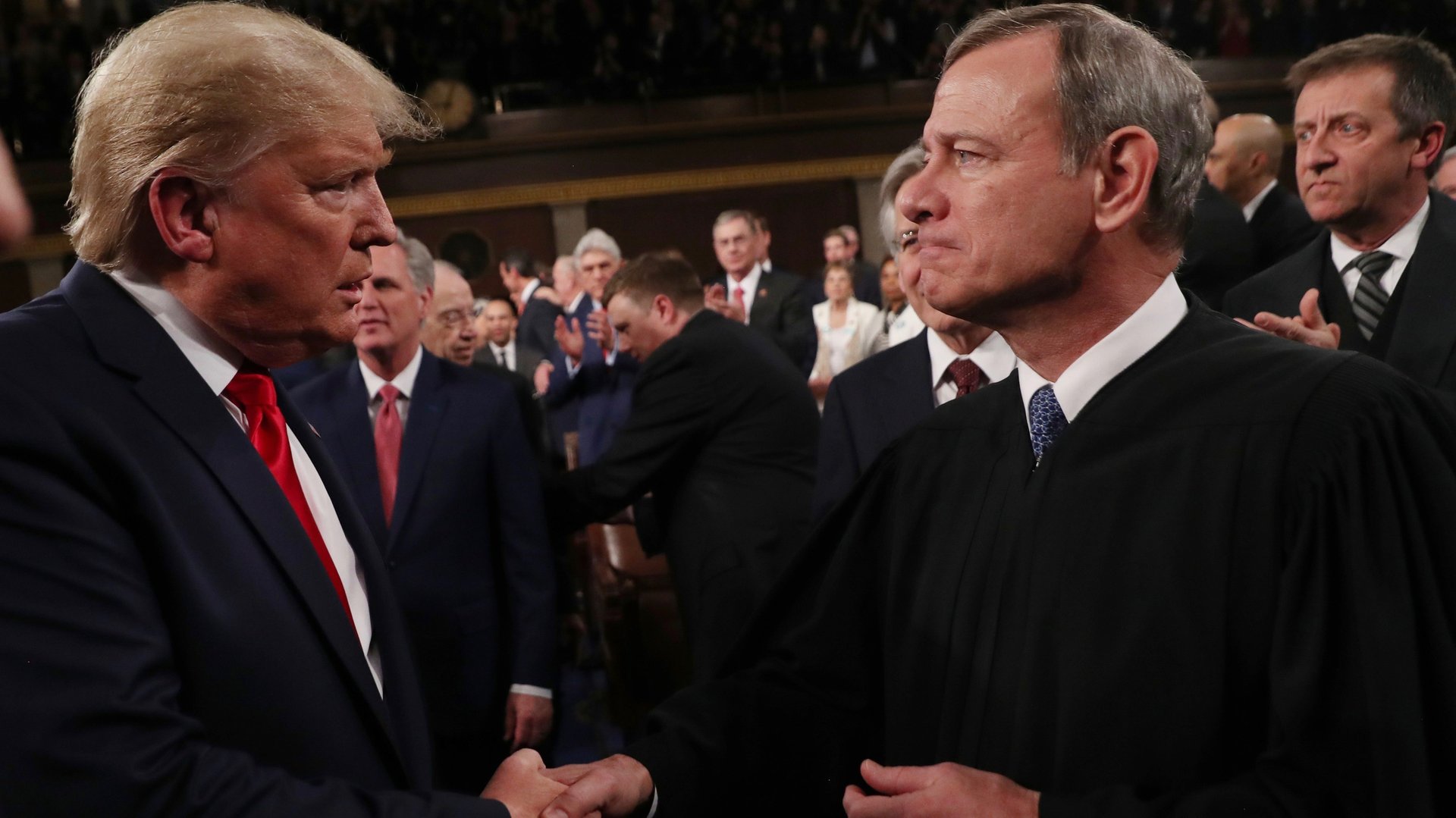

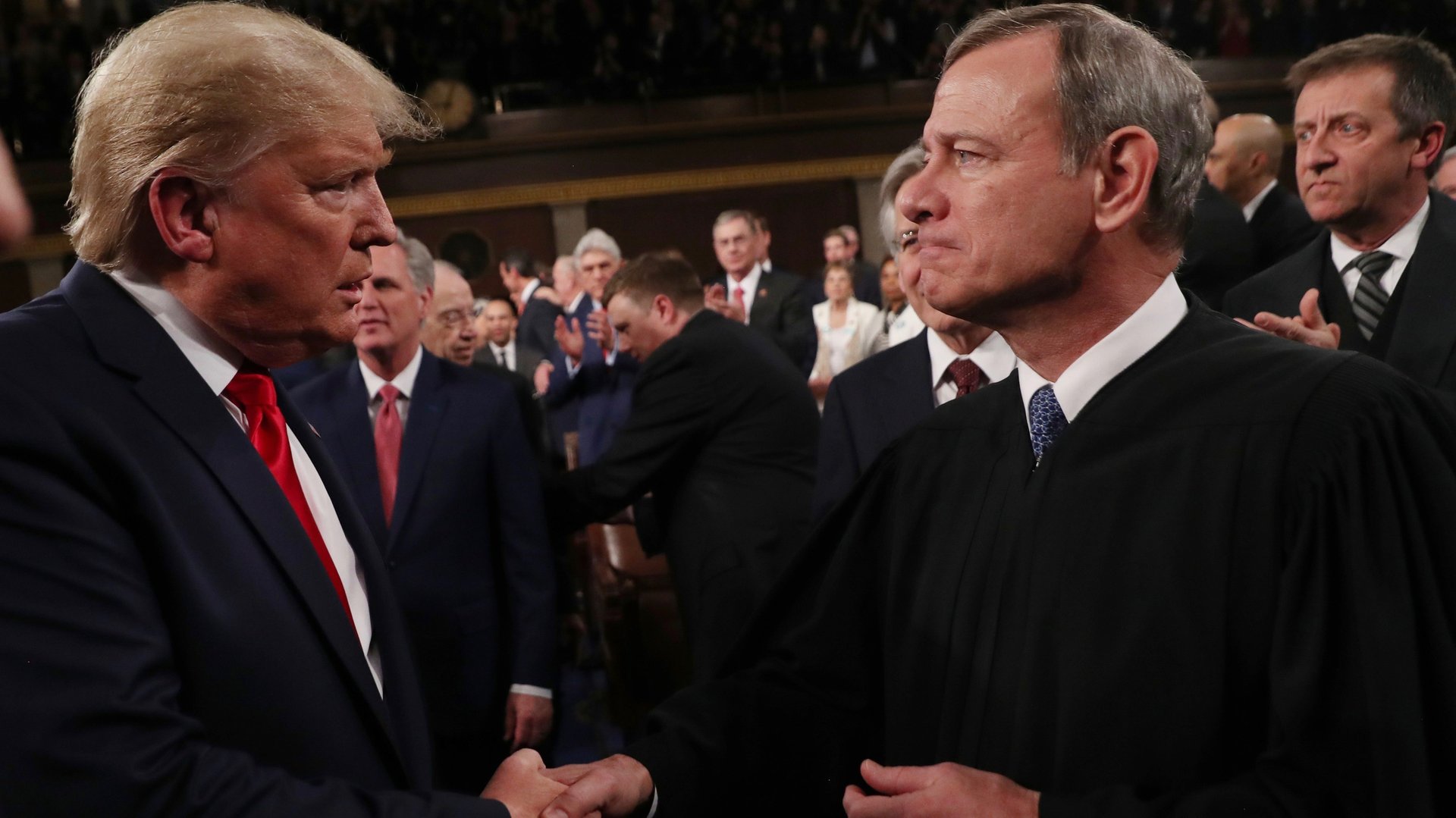

That claim seemed to rub chief justice John Roberts that wrong way. He noted that the president’s brief begins by declaring vast congressional overreach but “pulls back” from that by the end.

“I want to make sure I understand the scope of your argument,” Roberts said. “Do you concede any power in the House to subpoena personal records of the president?”

“Quite frankly,” Strawbridge replied, “Congress has limited power to regulate the presidency itself.”

The chief repeated a version of the same question again—this time in a tone that clearly implied one correct answer. “Does your position recognize that Congress may have such authority,” Roberts pressed the president’s attorney.

Forced to concede, Strawbridge finally admitted that Congress has some power in some cases to request personal records of the president. But he contended that in these matters the House committees lacked the proper authority because the claimed rationale is a pretext. The breadth and scope of the subpoenas show that House oversight committees don’t really plan to amend or pass laws based on findings but simply to harass the president.

Order of operations

Trump had more than one lawyer on his side. Principal deputy solicitor general Jeffrey Wall told the court that the cases before it were truly “historic” for the extraordinary way the subpoenas “target” the president’s personal papers, showing political hostility rather than pure legislative purpose.

This prompted Roberts to question whether the federal government was really asking the justices to “probe into the mental processes of legislators.” Could the court legitimately question the motives of lawmakers doing their jobs in the name of protecting the president? Was the administration asking the justices to start cross-examining elected officials?

Wall reassured the chief that he need not do any such thing. All the court has to do is look at the House committees’ records to realize they don’t have a sufficiently specific purpose.

Sure, legislators may legislate about any topic, which means anything could theoretically be the basis for a subpoena based on future legislative needs. And Trump could arguably make a good case study for future finance laws just as Jimmy Carter might have made a good case study on peanut farming. But it’s not “too much to ask” that the House committees justify their needs in detail.

This complaint only seemed to annoy Ruth Bader Ginsburg, who promptly set Wall straight as an errant schoolboy. “One must investigate before legislation,” Ginsburg lectured the attorney. “The purpose of investigation is to frame the legislation…The purpose is to expose the problem and then address it.” She added that Congress may decide if, for example, there should be laws on disclosure of tax returns. After all, before Trump, presidents offered these up voluntarily.

The Notorious RBG was obviously miffed. The Trump administration was asking the court “to impugn Congress’s motive” when it wouldn’t even second-guess a cop, she chided Wall. “If he stops the car because he says it ran a red light…we don’t allow subjective investigation [into his intent]. Here you are distrusting Congress more than a cop on the beat.”

Off limits

The House committees’ counsel also faced resistance, however. Roberts asked for one example of a single topic that might not fall into Congress’s legislative purview. Douglas Letter, the legislators’ representative, struggled to respond. Lawmakers can legislate on pretty much anything but the courts can oversee cases where there are allegations of harassment, he offered.

This failure to name a topic off limits to Congress came up again and again. The justices were struggling to come up with a “limiting principle,” some way to ensure that Congress’s power to investigate and oversee doesn’t just translate into unchecked harassment.

Samuel Alito claimed to be “baffled” by Letter’s reassurance that courts can “take care of” the harassment issue on a case-by-case basis. Alito pointed out, “That is the issue here.”

How precisely should the court ensure the committees weren’t just messing with the president? “You couldn’t give the chief justice even one example of a subpoena that would not be legitimate. So the end result is that there is no protection whatsoever…against the use of presidential subpoenas.”

Alito could not have sounded more annoyed asking and answering his own questions. “So the answer is just is it relevant to some conceivable legislative purposes? Not much protection. In fact that’s no protection, isn’t it?”

Brett Kavanaugh also expressed concern, seeming to lean toward the president’s arguments while trying to appear balanced in his query. Kavanaugh summed up the issues like this: “Which I think come down to the idea of limitless authority and how to deal with that.”

The justice explained to House counsel that “the other side” believes allowing the subpoenas would be a grave threat to presidents and maybe other government officials. He was worried “about the harassing nature” of the requests and not reassured by alleged legislative purpose. “Everything can be characterized as pertinent to a legislative purpose,” Kavanaugh protested.

His protestations may well hold the answer on striking the right balance. Perhaps it’s that Congress has the right to exactly what the House committees asked for from Trump’s associates because it can indeed legislate on any topic.

But based on today’s questioning, there is little unanimity on the bench. A decision—and surely dissenting opinions—can be expected by term’s end in late June.