Coronavirus has upended the profit incentives for pharmaceutical research

Fighting a pandemic will take more than scientific expertise and a collective sense of panic. It will take billions and billions of dollars.

Fighting a pandemic will take more than scientific expertise and a collective sense of panic. It will take billions and billions of dollars.

Anthony Fauci, director of the US National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease (NIAID), said in April that researchers are “on track” to find, create, and produce a coronavirus vaccine in 12 to 18 months. That timeline is significantly shorter than standard practice—by more than a decade—and is only possible if governments throw money at the problem.

Vaccine manufacturing and production costs about $500 million on average, says Stanley Plotkin, a physician whose research contributed to the development of vaccines for rubella, rabies, and polio. Even under normal circumstances, market incentives are rarely strong enough to encourage taking on those costs, and rushing the process only drives up the bill. Because it takes months to manufacture a vaccine, production must begin long before researchers know if their Covid-19 vaccine will work. Few rational companies would take on this cost. So public funding must come to the rescue: As of June, the US government has invested more than $2 billion in various companies’ vaccine trials.

Public funding often shapes responses to pandemics and public health issues, says Tahir Amin, co-founder of I-MAK, a nonprofit focused on lowering drug prices. But coronavirus is different. “The level and scale that we’ve seen during Covid-19 has been unprecedented,” says Amin.

The money flooding the marketplace is upending how companies evaluate risk and pursue research. As public-private pharmaceutical partnerships change the way companies develop and produce drugs for Covid-19, they also shape the way pharma can profit. Companies have the right to set the price of vaccines, even when they use taxpayer funds to develop them. But accepting that money makes them answerable to both the public that buys their products and to their shareholders. Plus, a seldom-used US law allows the federal government to demand a license to any drug created with the help of government funds.

This kind of intervention would be less necessary if the market rewarded vaccine production. But typically, it doesn’t, says Richard Frank, professor of health economics at Harvard Medical School and assistant secretary for planning and evaluation at the US Department of Health under the Obama administration. Consumers tend to undervalue preventive healthcare because of a bias toward the present.

And vaccines don’t have to be used by everyone to be successful, which means individuals’ incentives don’t reflect the full benefit of vaccination. “By my getting vaccinated, I improve your chances of not getting the disease,” says Frank. “It tends to drag down the willingness to pay in the marketplace for those products.”

The risks of investing in vaccine production are only exacerbated during a pandemic. Multiple vaccines are competing, and no company knows if their product will be successful. In the US alone, 12 different companies are currently racing to create a vaccine, though many are still in preliminary stages of research. Worldwide, 10 Covid-19 vaccine trials have advanced to human trials.

The US government has responded with international investments in vaccine development. The Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA) gave $1.2 billion to AstraZeneca to partner with the University of Oxford in producing its vaccine, while French company Sanofi initially said it would give its vaccine to the US first, thanks to US investments. (Sanofi later backtracked under public pressure in France.)

So far, the investments have worked to accelerate research. Already, two Covid-19 vaccines are in phase one trials; seven are in both phase one and two trials; and one, headed by Oxford University’s Jenner Institute, is midway through phase one, two, and three trials simultaneously.

Similar public-private partnerships have worked in the past. Government investments spurred the development of H1N1 and Ebola vaccines in recent decades. Public money also went into vaccines for SARS and MERS, which still don’t exist; in those cases, interest and money—public and private—dried up as the disease’s spread slowed. “People start to disinvest once there’s no market there,” says Amin.

Demand for a Covid-19 vaccine, though, is unlikely to evaporate any time soon. To pharma companies, Covid-19 represents both a deadly disease and a massive market. The threat of coronavirus is keeping the world on lockdown, and millions of people are desperate for a vaccine. Government funding will soften the investment blow for those vaccine trials that fail worldwide. A windfall awaits whichever company finishes first.

Coronavirus drugs play second fiddle to the vaccine

The surge in public funding has also flowed to companies researching therapeutic drug treatments, though investment in this sector is less competitive. “You see a pretty intense race to get a vaccine,” says Frank. “Therapeutics has got off to a somewhat slower start.”

Investing in drug research carries its own risks. Effective drugs could significantly reduce time spent in emergency care and alleviate the pressure on hospitals. But if a vaccine does materialize to eliminate the disease, then drug treatments will quickly become superfluous and companies’ investments would evaporate. “The private sector is going to respond rationally,” says Frank. “It’s going to respond more quickly when the payoff is clearer.”

The public sector hasn’t ignored the need for therapeutics: BARDA has given $837 million to develop various coronavirus drug treatments. And the government agency is openly soliciting proposals for further therapeutic development, said a spokesperson. But there’s considerably more investment explicitly dedicated to vaccines. On top of the BARDA’s $2 billion vaccine investment, a March coronavirus bill granted $826 million for NIAID to develop coronavirus vaccines, tests, and treatments, plus an extra $300 million explicitly to ensure that vaccines will be affordable.

Frank says there should be more sustained investment to fund research into how generic drugs, in particular, could be used to treat coronavirus. New drug molecules can be patented, typically for five years, meaning that companies control the sale and receive all profits from their creation. Once patents expire, other companies can manufacture and sell the same generic drug, which tends to drive down the price.

The government has invested in several coronavirus trials for existing antivirals, and one generic drug with unestablished efficacy against Covid-19, hydroxychloroquine, has been granted emergency use authorization by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA). But given the relative ease of studying generic drugs (companies don’t have to go through phase one trials to establish safety), Frank says the government could do more to invest in and encourage generic therapeutics research.

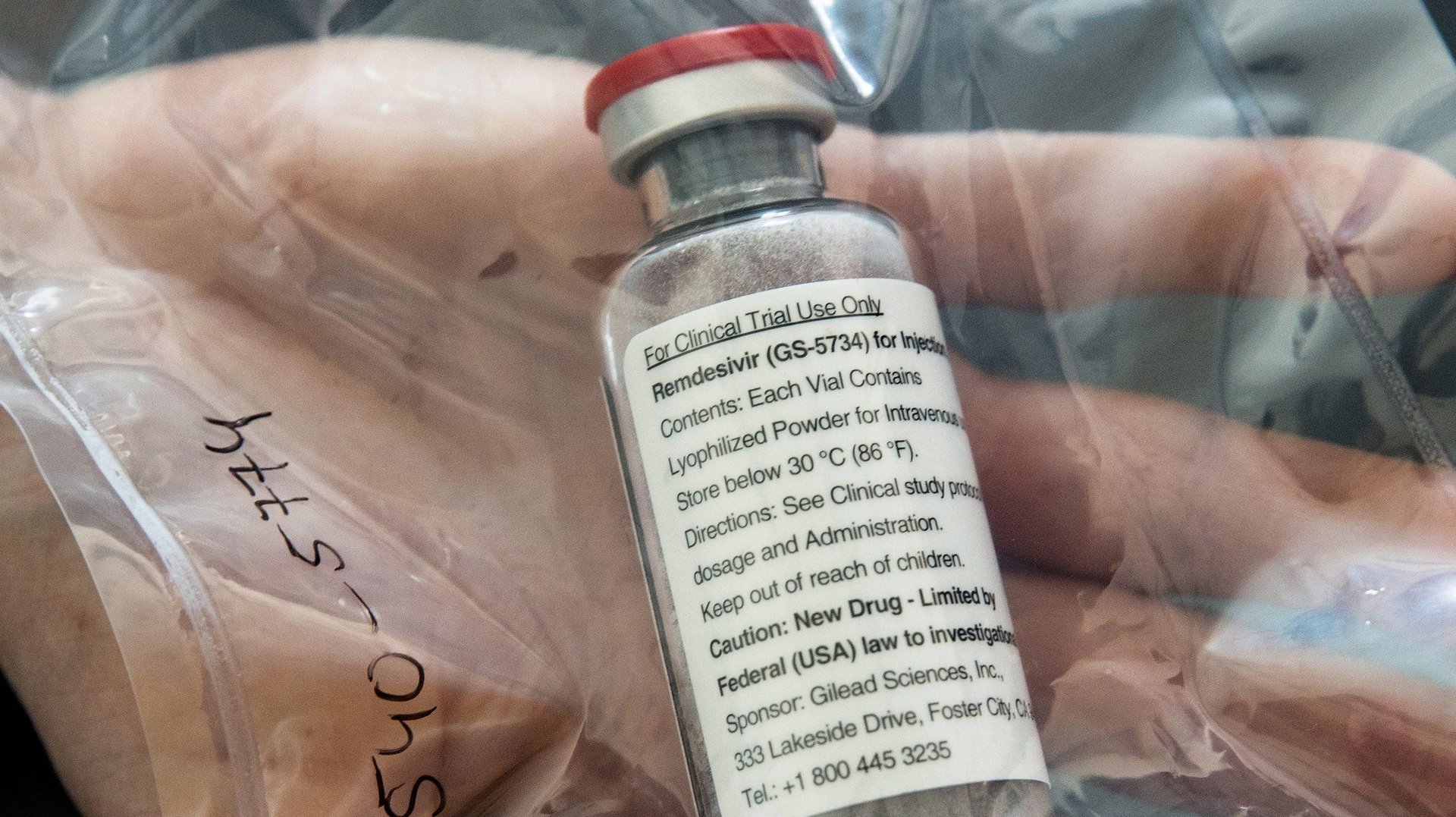

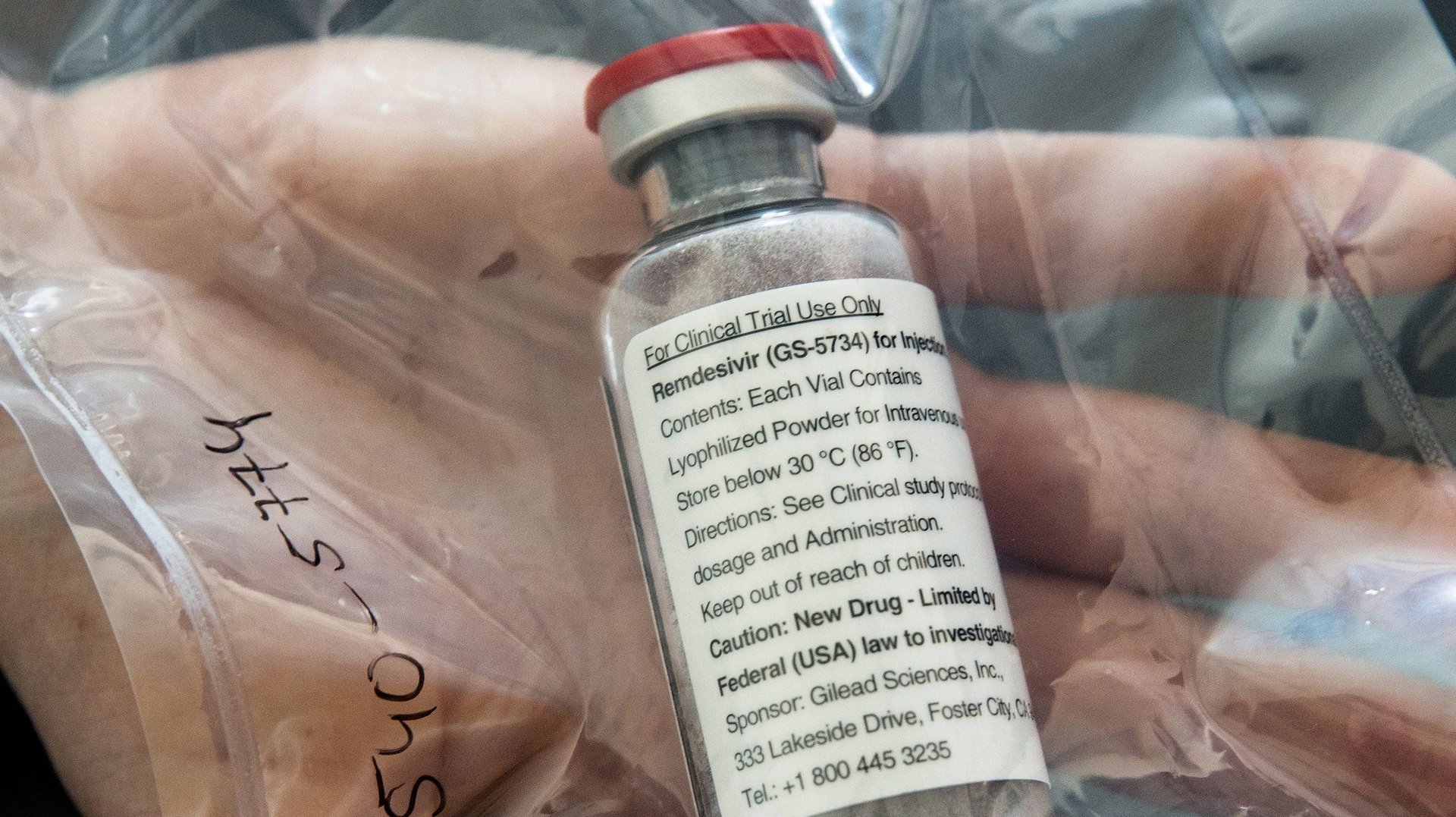

So far, the most promising therapeutic for Covid-19—and the beneficiary of the most public funding—is not a generic drug but a newly-authorized creation: remdesivir. California-based Gilead Sciences originally developed this antiviral to treat Ebola, using $34.5 million in government funding, and later tested it against other coronaviruses. In total, the US government has spent at least $70.5 million on remdesivir research and development, according to Public Citizen, a non-profit consumer advocacy group.

In March, Gilead requested even greater financial incentives from the government, by asking the FDA to grant remdesivir “orphan drug status.” Orphan drugs are developed to treat extremely rare medical conditions; the rarity of the illness means that companies can’t profitably develop treatments without government help. This designation would qualify Gilead for tax credits, waive FDA fees, and prevent competitors from creating generic versions of the drug for seven years.

Coronavirus, though, is not a rare disease. Following widespread outrage, Gilead asked the FDA to rescind the designation.

As it stands, Gilead will still be able to market remdesivir exclusively for five years. The company has licensed the drug to several Indian and Pakistani companies, but maintained the wealthier US, European, and Australian markets for itself. “Some analysts have predicted they’ll make a billion,” says Amin. Gilead did not respond to requests for comment. The company may be able to make hay out of this moment. But there are other major forces that could disrupt its ability to make money off of research.

Profiting off coronavirus

The pharmaceutical industry could face serious backlash if it appears to profit excessively from the pandemic. Not only is there widespread and desperate need for vaccines and treatments to limit the spread of coronavirus, but using taxpayer money to fund research creates added pressure to set fair prices.

In March, pharmaceutical lobbyists struck language from a $8.3 billion spending package that would have allowed the federal government to take action if it believes vaccines or treatments developed with public funds are sold at too high a price. Any limits on coronavirus drug prices will be set by public perception of decency, rather than the law. “If people aren’t getting the drug, there will be outcry,” says Amin.

After the FDA granted emergency use authorization, Gilead donated 1.5 million doses of remdesivir—enough to treat 140,000 patients—to the US government. This choice reflects the public need for treatment and pressure to balance public image with shareholder demands for profit. But it’s not the company’s only potential motivation.

“The [corporate] gestures that might be made in a time like this mostly seem to be directed at staving off more severe governmental action,” says Jorge Conteras, a University of Utah law professor specializing in intellectual property. Though the US government has largely taken a hands-off approach towards the private sector in recent decades, it technically has the power to override patents.

Under the Bayh-Doyle Act of 1980, the US government has “march in rights” for any drug created with the help of government funds, meaning it can demand the patent-holder license the drug to third parties to address health needs. Meanwhile, under statute 28 U.S.C. § 1498, the government can use patented drugs and technology without the permission of the patent holder as long as it provides reasonable compensation.

If the government wanted to take on the role of providing coronavirus testing, treatment, and vaccination, it would have the legal right to do so. “The NIH [National Institute of Health] has clear mechanisms to distribute drugs to the public sector to meet demand,” says Conteras. “They’ve never exercised it, but this might be the time it’s most warranted. There are strong arguments that remdseivir had significant federal participation.”

Other companies seem to be aware of the potential for legal recourse. “This is presumably why AbbVie freed up IP rights on Kaletra,” says Conteras. HIV medication Kaletra shows promise as a coronavirus treatment, but the drug was patented until 2026 in some territories worldwide, meaning trials couldn’t continue without AbbVie’s involvement. Israel was preparing to issue a compulsory license for the drug’s use when AbbVie declared it would not enforce its patent rights, thereby freeing up use of the drug for coronavirus research and treatment. The company did not respond to requests for comment.

Several politicians and public health groups have called for patent enforcement to be more broadly abandoned during coronavirus. The World Health Organization has backed a voluntary patent pool where companies would share intellectual property rights. So far, there is little take up. But there are unusual examples of major competitors choosing to collaborate on coronavirus treatments, such as rivals Sanofi and GSK joining forces to create a Covid-19 vaccine.

These partnerships amount to “unprecedented” levels of inter-company collaboration, says Jocelyn Ulrich, deputy vice president of Medical Innovation Policy at Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America (PhRMA), a trade group representing pharmaceutical companies. Companies are committed to solving problems as quickly as possible, rather than creating a profit, she says. “It’s all hands on deck.”

Frank is more circumspect: Corporations are more likely to pursue unusual partnerships under the urgency to respond to coronavirus, but their underlying interests have not changed dramatically.

Companies have responsibilities to their shareholders, and even in the face of a pandemic, they can’t afford to fund research without expecting reward. Currently, these risk evaluations are skewed by massive levels of public support balanced by the need to avoid the appearance of profiteering. Amid these financial concerns, pharmaceutical companies must also reckon with coronavirus itself. “They are in the business of human health,” says Frank. “They’re businesses, but they spend their time fighting disease. This is a big one.”