Despite what you may hear from dodgy sources on social media, there is no known treatment for Covid-19, the illness caused by the novel coronavirus. Right now, there are only clinical trials.

Among the drugs being investigated is remdesivir, an experimental antiviral made by the US drug company Gilead Sciences. It has been characterized as one of the most promising by health authorities, including WHO officials—though that optimism is inspired only by anecdotal information. US data on remdesivir’s performance in controlled clinical trials is expected next month, and data from late-stage trials conducted in China will be released by the end of April.

The US military, however, has already secured access to remdesivir for its service members.

On March 10, the Pentagon announced a deal with Gilead Sciences in which the pharmaceutical company would supply the military with the intravenous drug at no cost. “Together with our government and industry partners, we are progressing at almost revolutionary rates to deliver effective treatment and prevention products that will protect the citizens of the world and preserve the readiness and lethality of our service members,” Army Brig. Gen. Michael Talley, commanding general of the US Army Medical Research and Development Command (USAMRDC) and Fort Detrick, Maryland, said in a media statement at the time.

Remdesivir has already been given to more than 1,700 Covid-19 patients globally. Many thousands more are receiving it in trials or in individually managed “compassionate use” cases approved by Gilead before the company shut down that pathway near the end of March.

To the uninitiated, news of the military’s deal with Gilead was surprising, shining a light on the military’s unique ability to acquire medications before the FDA has signed off on the same drug for average Americans, if it ever does. But it’s not the first time that the military has entered such an arrangement—it’s just the first time the drug in question has been one of exceedingly high interest to the public.

Here’s what we know about how the process works, and why the Pentagon decided to pursue a deal with Gilead.

The US army division that becomes a “laboratory”

The US military has an obvious strategic and humanitarian interest in protecting its soldiers from pandemic diseases. That’s a task that should be easier to orchestrate now, when the country is not involved in a major war, than during a pandemic like the Spanish flu of 1918. One hundred years ago, the most successful practices for dealing with the flu’s devastation were some of the same in use now: social distancing, quarantines, and good hygiene, as a recent report from RAND explains.

Today, however, the Pentagon also has a unique team called Force Health Protection in its corner. This group is devoted to managing and procuring investigational drugs and other medical products on behalf of the US Army Medical Materiel Development Activity (USAMMDA), a division of the USAMRDC.

Under army regulations, the USAMMDA can enter into a special contract—a “Cooperative Research and Development Agreement”—with an organization like Gilead and become designated as a “laboratory,” a USAMMDA spokesperson said. In this way, the Department of Defense has “the capability to use investigational medical products, that are in development, with enough safety, efficacy, and dosing information to respond to high consequence threats when there is no FDA-approved or feasible treatment.”

It’s debatable whether we would call the practice “treatment” or “research.” Although it appears on the ClinicalTrials.gov website as an expanded access program, the USAMMDA told Quartz that the contract with Gilead “is not part clinical trial but a treatment protocol.”

The role of Force Health Protection was also profiled in an official interview with James Karaszkiewicz, a senior scientist for the team, published in 2018. He said the unit “forms a bridge between the regulatory world and the product development world.”

“We make products available to the Warfighter, and in some cases dependents, prior to their licensure,” he said. “But all of this is done under appropriate US Food and Drug Administration regulatory mechanisms.” The team’s staff is familiar with niche regulatory mechanisms around emergency use authorizations and expanded access programs for investigational drugs, he explained, calling these obscure pockets of FDA rules “the center of our world.” In 2018, Force Health Protection unit was managing 11 medical products in total.

In an ideal scenario, Karaszkiewicz said, the FHP selects drugs or devices that are roughly halfway along the standard commercial pipeline, so most of the products they handle have at least completed the first two stages of standard FDA trials and have been deemed basically safe, while showing some efficacy in a patient population. (Drug companies must submit data from large phase three trials before the FDA will consider a product for approval.)

Remdesivir fits that profile. The compound was crafted more than 10 years ago and later developed as a potential treatment for the Ebola virus outbreak in West Africa in the mid-2010s (it had minimal effect). But researchers continued to test remdesivir against other viruses and discovered it worked to block other coronaviruses from replicating in animal studies, including those behind Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) and Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS). Phase two trials of Covid-19 patients treated with remdesivir had already been completed when the USAMMDA made its announcement about acquiring the drug.

“Remdesivir was chosen because it was the most mature, broad spectrum antiviral drug in development and showed activity in vitro and in animal models in decreasing the viral replication against coronaviruses,” the USAMMDA said in its statement to Quartz.

More than an insurance policy

There are some key differences between remdesivir and the typical drug that would interest Force Health Protection. Karaszkiewicz explained in the 2018 interview that most of the experimental medications that his team manage target a disease or condition that does not pose a threat to the vast majority of Americans.

Drug development for these kinds of diseases would be lengthy or non-existent. At the very least, recruitment for clinical trials would be slow. “There are diseases that just don’t occur in the US, so no one is going to make the investment to try and gain approval in the US for that particular indication,” he said.

Many of the division’s products are, in fact, “insurance policies,” hopefully never to be used because they’re designed for chemical or biological warfare, but managed and strategically stored around the world should they be required, he said. Other medications are intended to treat endemic diseases in specific locations.

By contrast, the demand for remdesivir and momentum behind its development could not be stronger or feel more urgent. Anthony Fauci, director of the US National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, has said that 100,000 to 200,000 Americans could die from Covid-19. At that time the military announced its deal with Gilead, 25 people in the US had died of Covid-19. As of today (April 9), the virus has taken more than 14,000 US lives, and killed more than 80,000 people globally.

Remdesivir is not merely an insurance policy. It’s currently being administered to service members who have tested positive for Covid-19, Quartz was told, and some patients have already been treated. The drug’s usage is being coordinated and positioned in the US, in the US European Command, and in the US Indo-Pacific Command. The announcement did not include details about how many doses Gilead Sciences would be providing the Pentagon; a spokesperson for the USAMMDA also declined to share specific numbers.

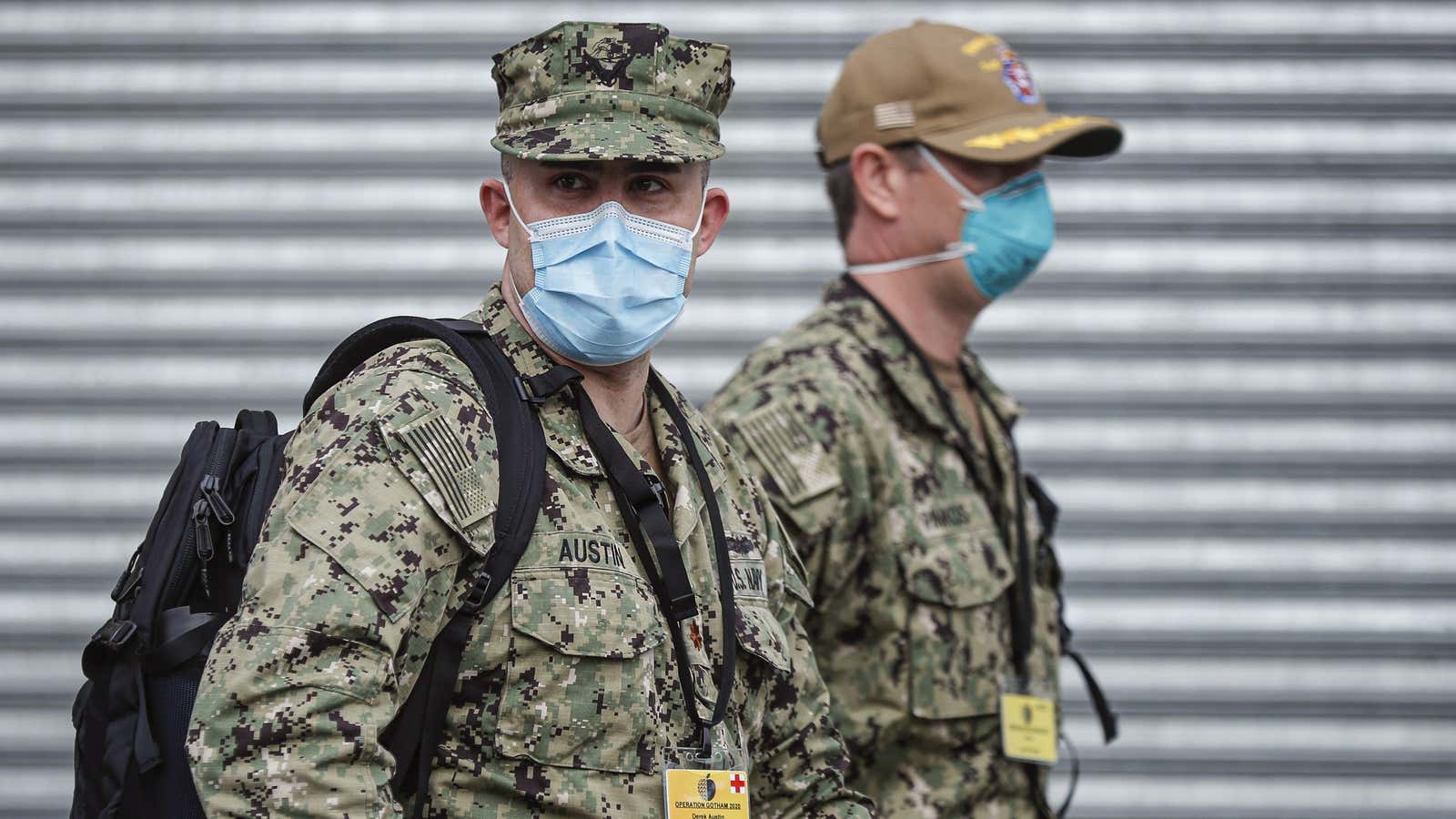

More than 2,000 Department of Defense personnel have been diagnosed with the illness as of April 9, as ABC reports. One member of the National Guard has died from the disease. An estimated 46,000 active service members are also responding to the pandemic in field hospitals in the US.

As soldiers are apparently given access to the drug, several other US and global clinical trials are underway to test its effects when introduced at various stages of disease development and for five- or 10-day intervals. Some citizens are “rushing” to join these research efforts, as CBS News reports. With results still pending, Gilead has announced plans to boost production and donate 1.5 million doses of remdesivir for clinical trials.