Dexamethasone’s supply chain is the most exciting thing about it

On June 16, researchers from the University of Oxford put out an intriguing press release: Based on data from thousands of people with Covid-19 in an ongoing study, a generic steroid called dexamethasone could save some of the sickest patients.

On June 16, researchers from the University of Oxford put out an intriguing press release: Based on data from thousands of people with Covid-19 in an ongoing study, a generic steroid called dexamethasone could save some of the sickest patients.

Although the research is extremely preliminary—the study hasn’t even been finished, let alone peer reviewed and published—it’s a ray of hope for the pandemic response. If those early results are confirmed, the drug has already been through safety trials, meaning hospitals could start using it it straight away. And even better, the drug has a robust supply chain that should prevent shortages based on extreme demand.

Shortages are a concern—and a justified one—for many other potential Covid-19 treatments. Doctors have struggled to access remdesivir, the antiviral produced by Gilead Sciences, since studies showed the drug improved recovery time in coronavirus patients. Or consider hydroxychloroquine, a drug that can treat malaria and the autoimmune condition lupus. After the US Food and Drug Administration authorized its emergency use in hospitals and US President Trump talked about taking it prophylactically, countries and states hoarded the drug, leading to a global shortage. (The FDA went back on its decision after two prominent scientific journals retracted studies that showed its efficacy.)

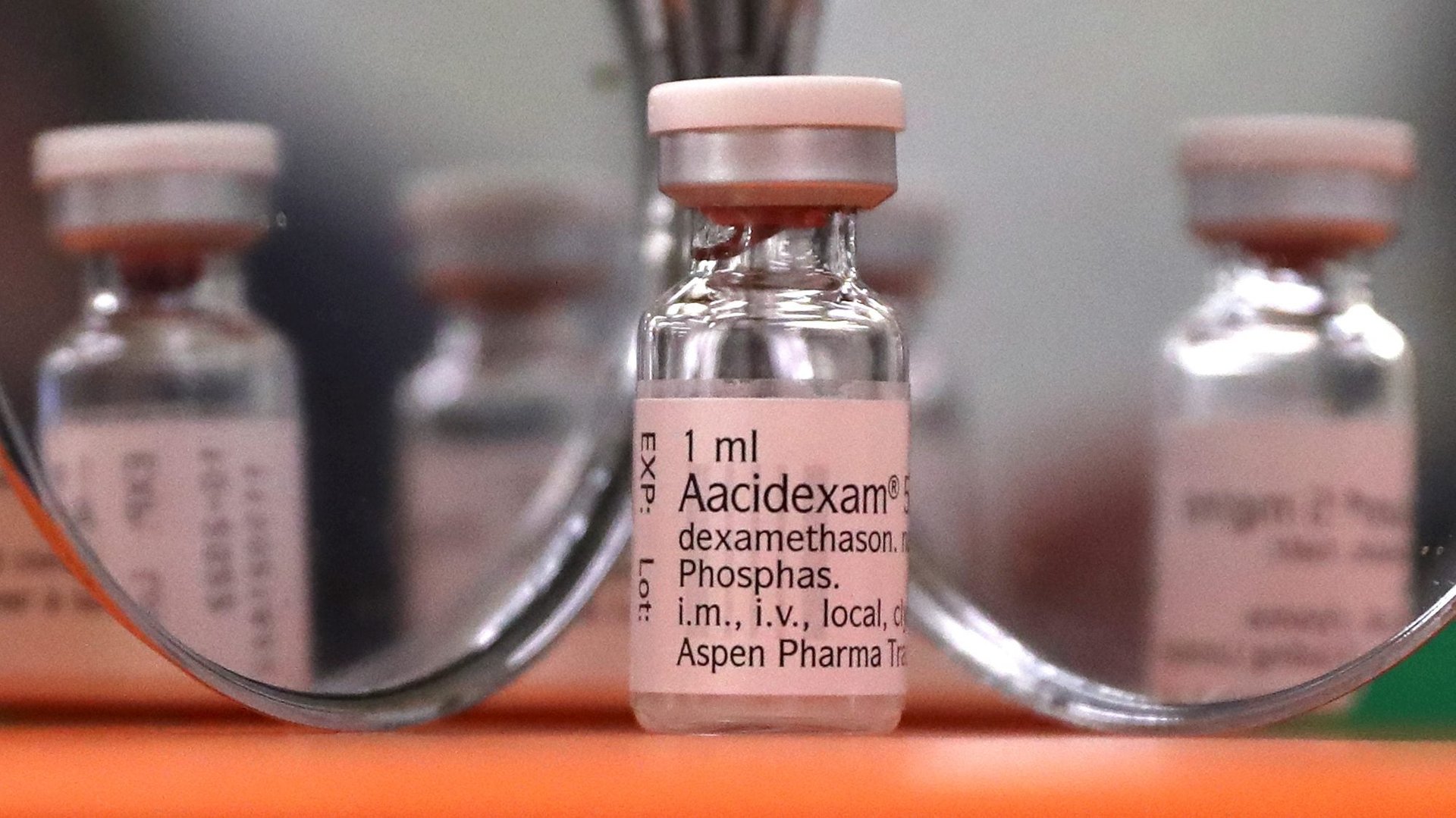

But shortages are less concerning for dexamethasone, says Michael Ganio, the senior director of pharmacy practice and quality at the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. For one thing, it’s a common drug that has been on the market for nearly 60 years. At this point, it’s generic. The US-based company Merck used to have exclusive rights to market it; today, manufacturing plants all over the world make and ship the drug.

On top of that, from a manufacturing standpoint dexamethasone isn’t complicated to produce, Ganio explains. The press release from Oxford researchers says that study participants received both oral and intravenous forms. Pills in particular are easier to make because they don’t require the same stringent quality-control checks as intravenous drugs, which can take up to two weeks. Harmful bacteria can live longer in liquid, whereas there’s very little water (if any) on the surface of pills.

Even if hospitals did run into shortages of dexamethasone, hospital pharmacists could make substitutions pretty easily. It’s a steroid, which represents a huge class of drugs. Like fentanyl delivers a much stronger dose of the opioid product in hydrocodone, dexamethasone is a more potent version of the active ingredient in cortisone. “In acute respiratory distress syndrome”—the main complication with severe Covid-19 cases—”there have been studies using steroids for decades now, with mixed results,” says Ganio.

The final bit of good news comes from a place of caution. The early release from the University of Oxford researchers said that dexamethasone was effective for patients who were on ventilators or other forms of supplemental oxygen—the sickest Covid-19 patients, in other words—and it took treating eight people on ventilators to save one extra life. There’s still no data on whether the drug would effectively treat other stages of the illness. It’s unlikely, therefore, that those who contract Covid-19 but are well enough to stay home and recover would receive it at this point, which could help to temper demand.

With any study that suggests a drug may be an effective treatment, scientists and doctors have to ask how it will get to patients. It’s not enough that the drug could work—those in need have to access it in time, too.