The history of the US ballot is a fascinating journey through the making of a democracy

The US prides itself on being the oldest modern democracy—its 244th anniversary is this weekend—and yet it’s only been an actual one for a century at best: It wasn’t until 1920 and the recognition of women’s suffrage that the whole adult population was, at least theoretically, recognized the right to vote.

The US prides itself on being the oldest modern democracy—its 244th anniversary is this weekend—and yet it’s only been an actual one for a century at best: It wasn’t until 1920 and the recognition of women’s suffrage that the whole adult population was, at least theoretically, recognized the right to vote.

Effectively, however, it’s truly only since 1965 that the Voting Rights Act effectively removed obstacles for Black citizens to vote, making full democracy in the US a pretty young enterprise.

What started in 1776 wasn’t a fully formed democracy, but rather a process—a democratic aspiration that started on hopeful, if shaky, foundations and then built on itself, fighting the forces of the status quo to add, one by one, real layers of democratic power. That is the essence of the great democratic experiment of America—one that is far from finding a perfect, fair balance of power, but exists and thrives only in its relentless pursuit.

Among the many fights, legal victories, and historic moments that mark this evolution, there is an artifact that stands out as a record of the journey: the electoral ballot.

It is, to be sure, an ephemeral one. As designer Alicia Yin Cheng writes in the introduction of her newly published book, This is What Democracy Looked Like, “as a material tool of democracy, the ballot should not, by its nature, be collectible.” Her book, tracing the history of the paper ballot with a wealth of reproductions of electoral artifact from the early 19th century to 2018.

In order to prevent fraud, ballots must be destroyed after the election in which they were used, so only a small minority of them survive today—especially from the 20th century onward, as officials put more effort in running fair elections.

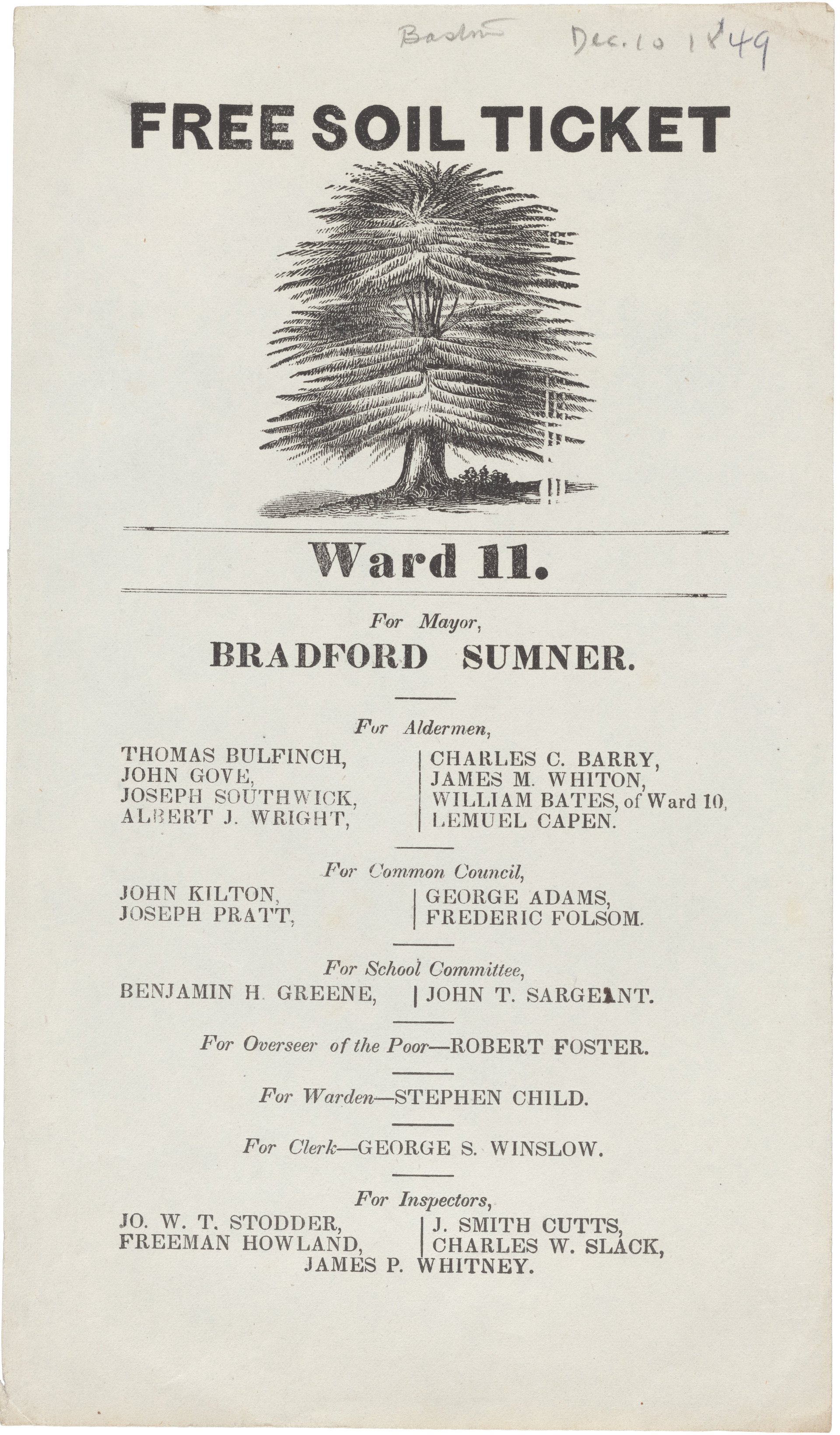

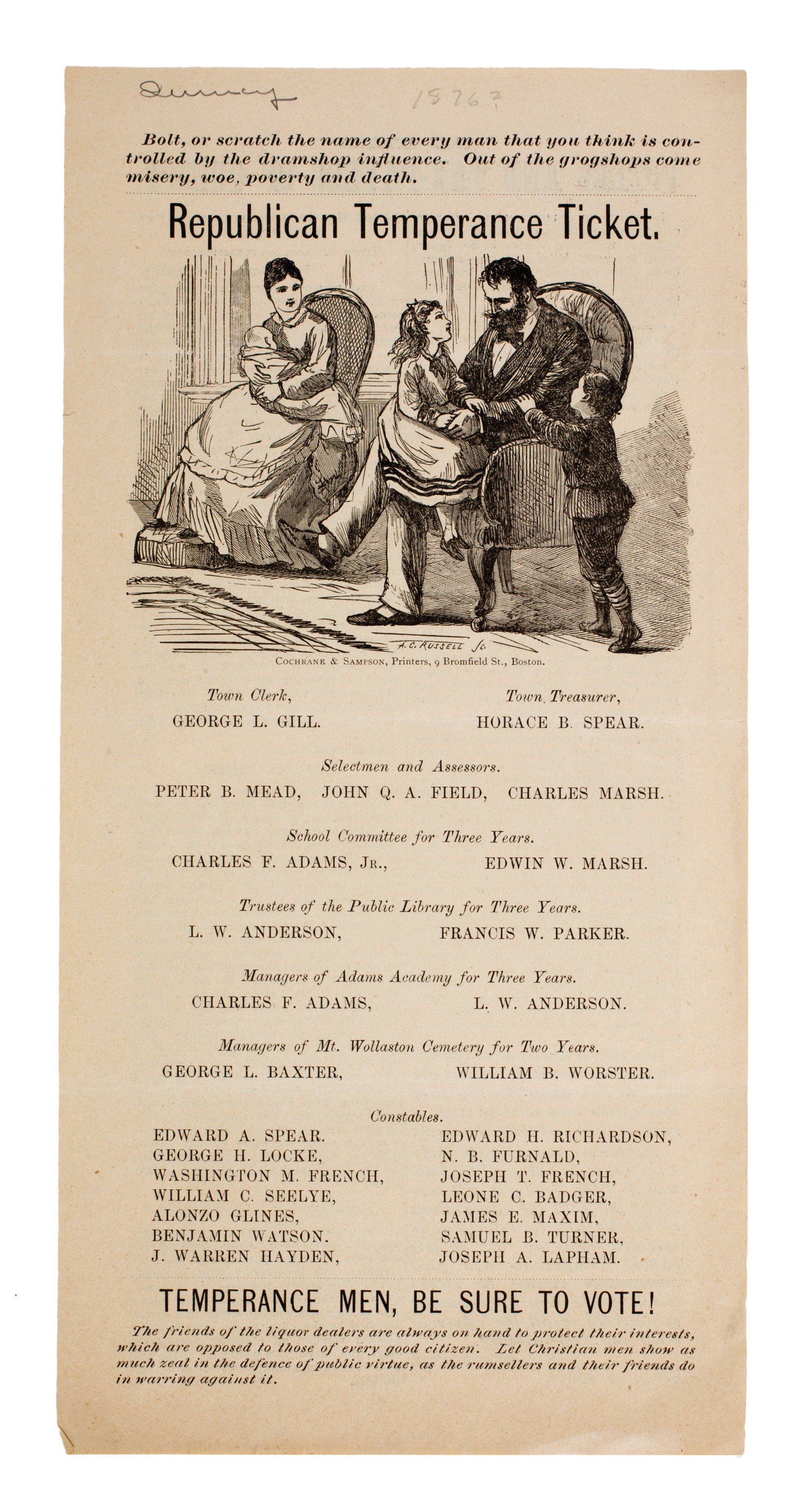

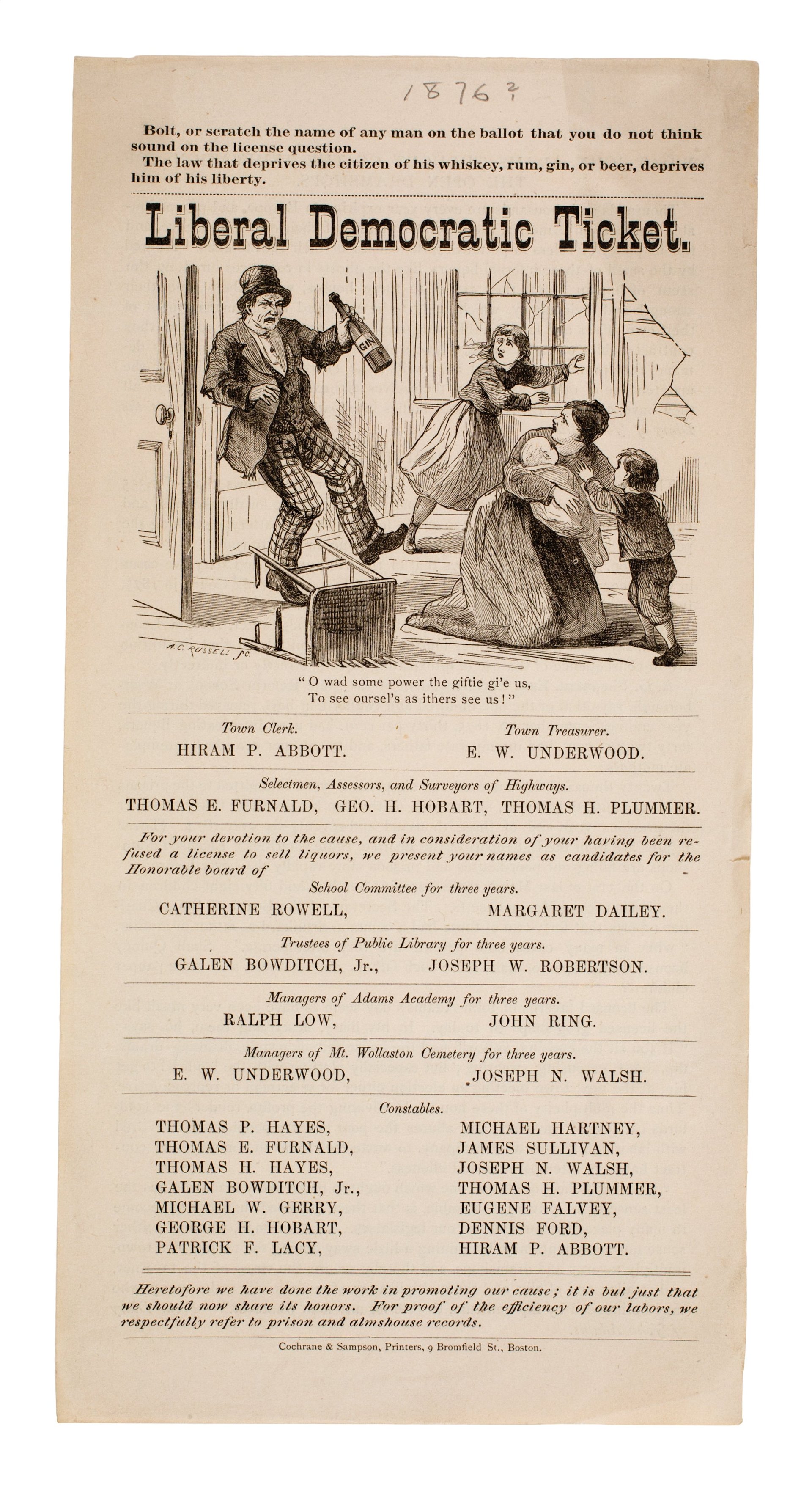

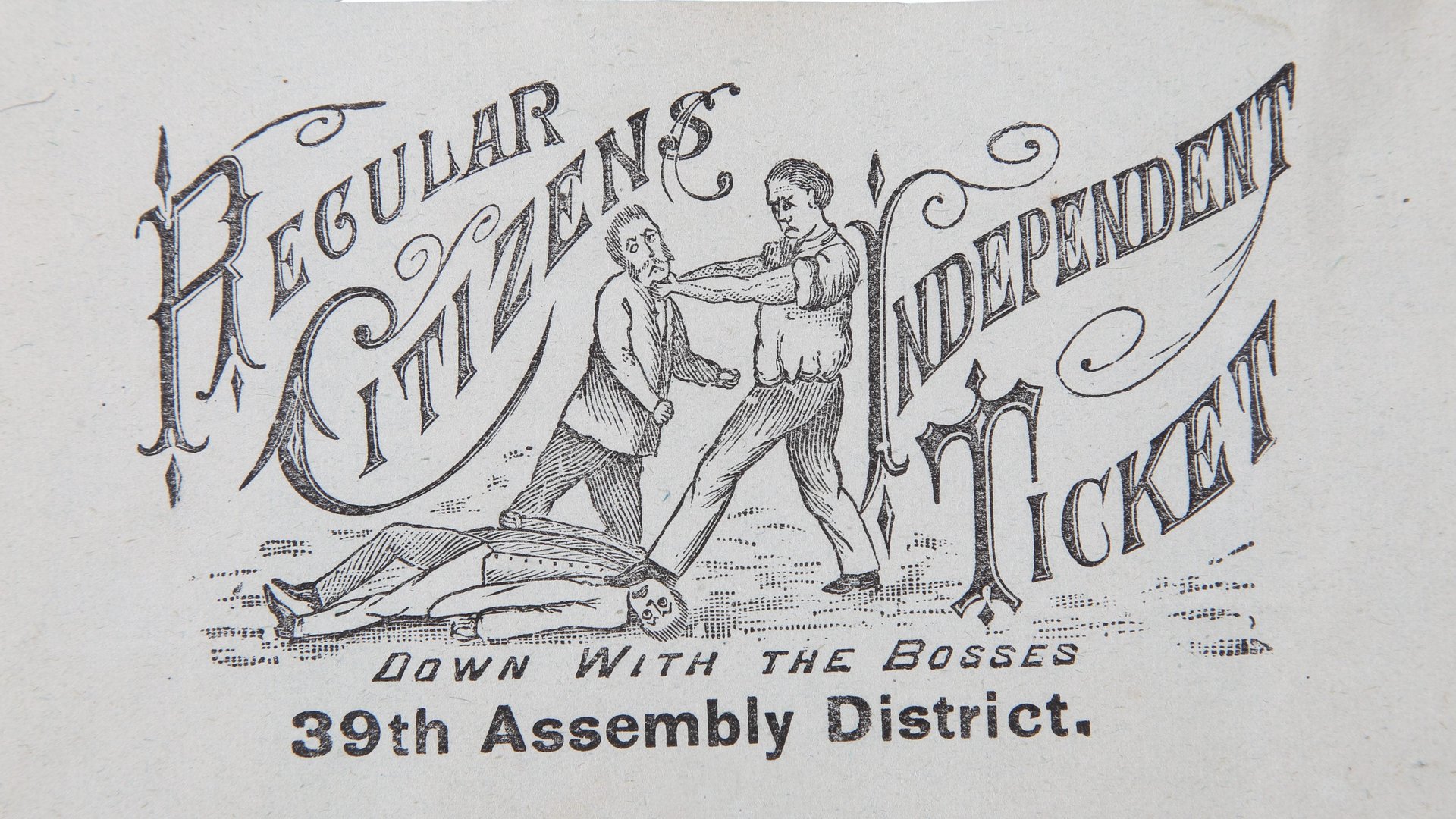

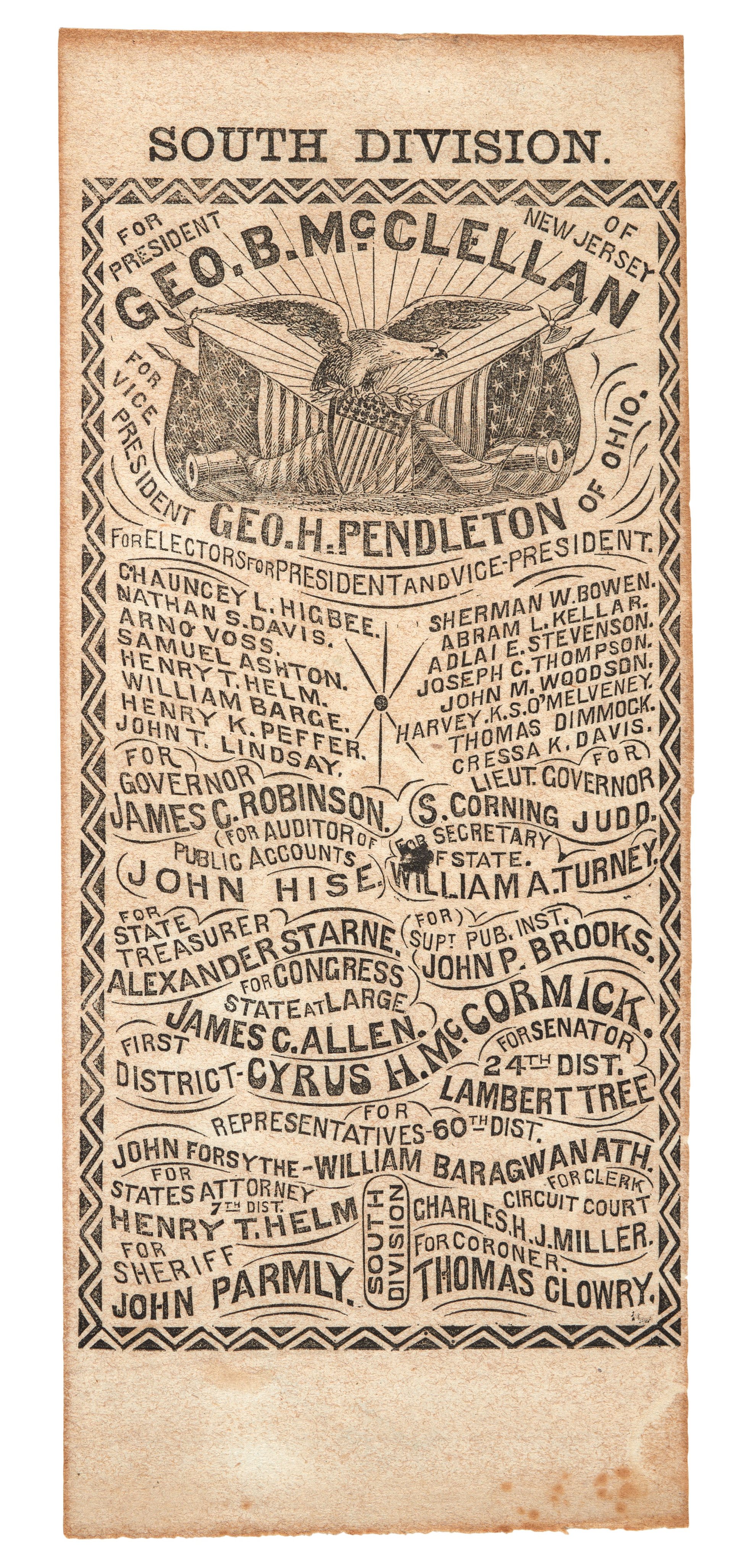

The majority of the artifacts contained in Cheng’s book are so-called tickets: pre-printed pieces of paper containing the full list of candidates of a party used in the 19th and early 20th centuries. At the ballot, a voter wouldn’t mark a ballot, but choose the ticket of their preferred party or candidate, and drop it in the polling box. These tickets were printed by the candidate or the party and supplied to voters, with little oversight.

Altogether, these tickets are a fascinating journey through the changing powers and values of the nation—as well as the technology that allowed them to be expressed, and changed, through the voting process.

On the basis of sex, race, class

Given America’s history, it is not surprising to see just how white, and male, democracy looked like till recently. Yet it’s still surprising to see race, sex, class, and religious privileges be not just enshrined but actively protected and fought for in the ballot.

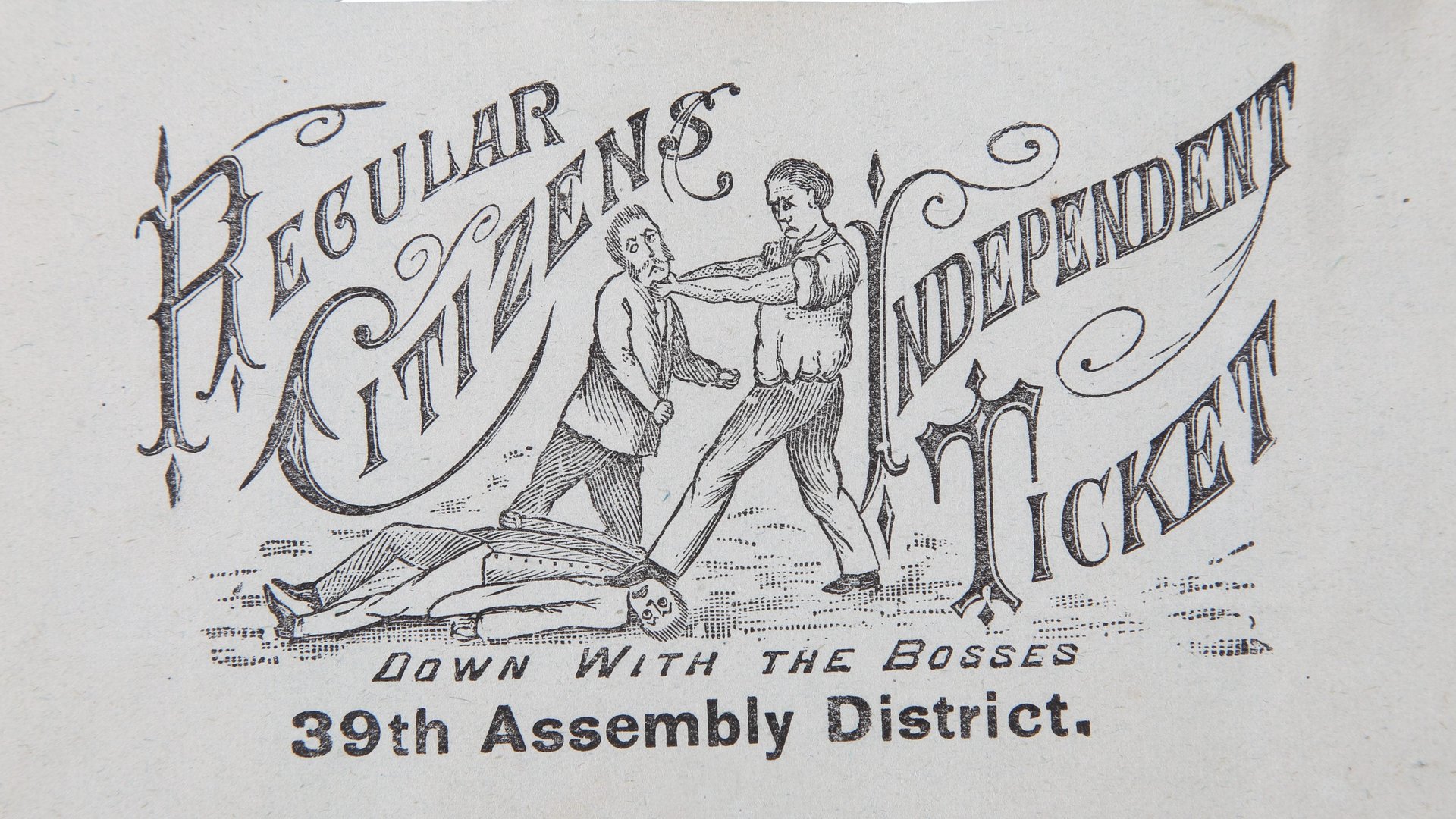

A whole series of tickets reproduced in the book, for instance, were printed for candidates supporting what would eventually become the Chinese exclusion act. They include crude depictions of Chinese people and culture, and even violent depictions of their expulsion. One such ticket, from the 1870s, for instance, in written in a mocking typeface deigned to mimic Chinese lettering.

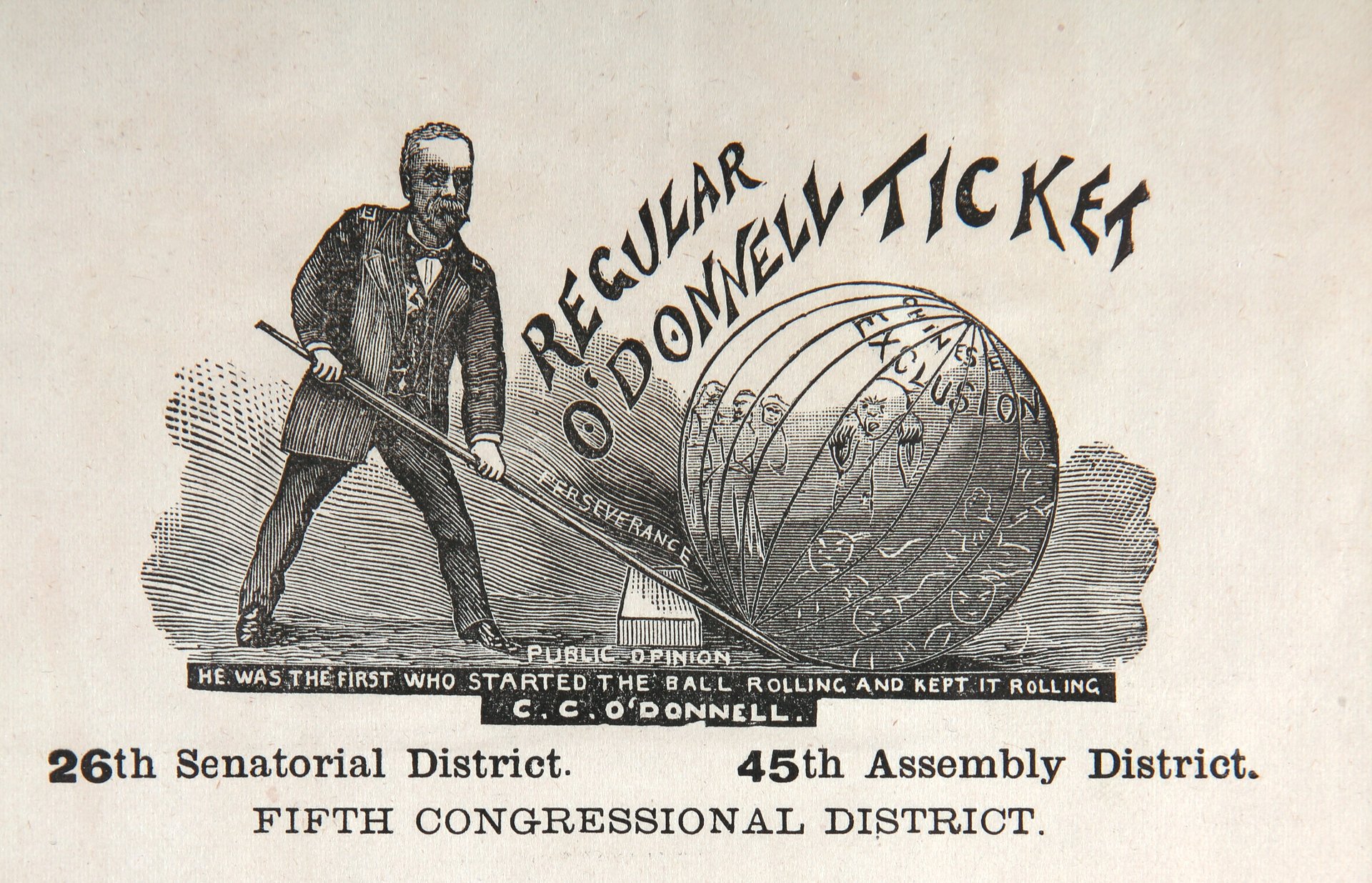

Another featured ticket, from the 1880s, stands for the “protection of white labor.” A 1846 ticket depicts a racially caricatured Black man in support of a constitutional amendment requiring Black citizens own property in order to vote in New York State. (The property qualification for Black people won overwhelmingly in New York that year.)

On the other hand, the ballots also show the counter movements—those that eventually brought the country closer to fairness. One 1849 Free Soil Party ticket, featuring an imaginatively depicted tree, is a reminder of the short-lived party, which later was folded into the Republican Party, with the single issue of opposing the expansion of slavery in the Western states:

Throughout the ballots, women are mostly absent—not just as candidates, but as persons deserving of specific measures. The exception is when they were used as props to promote the male candidates’ virtues as family men, as in these 1870s tickets for the Temperance Party, which suggested banning alcohol would make men better protectors of their wives and children:

Class struggle is very much present in the ballots, as well, and tickets show a wealth of long-lost workers parties, including the Labor Party, Working Men Party, and Farmers Party.

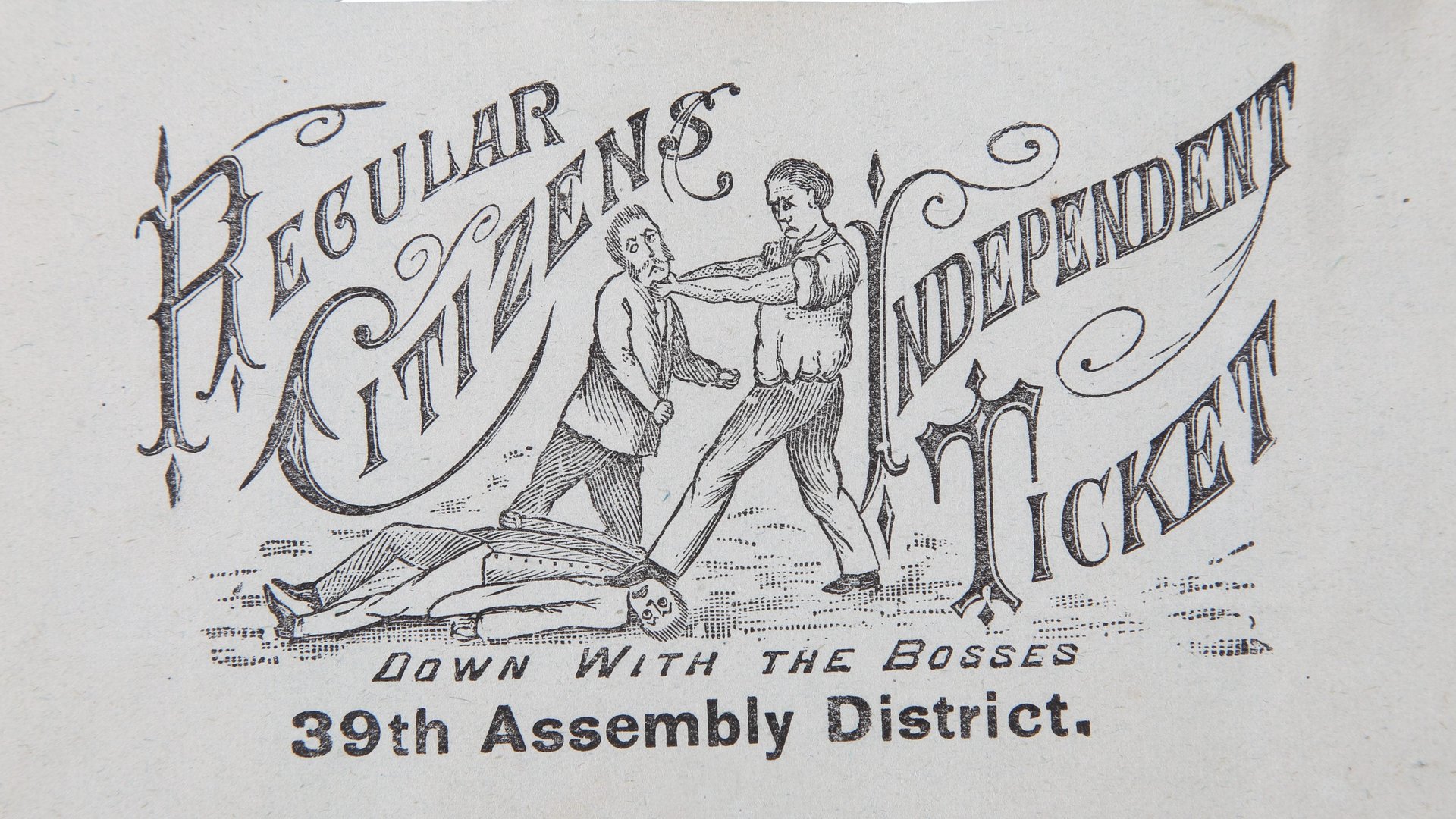

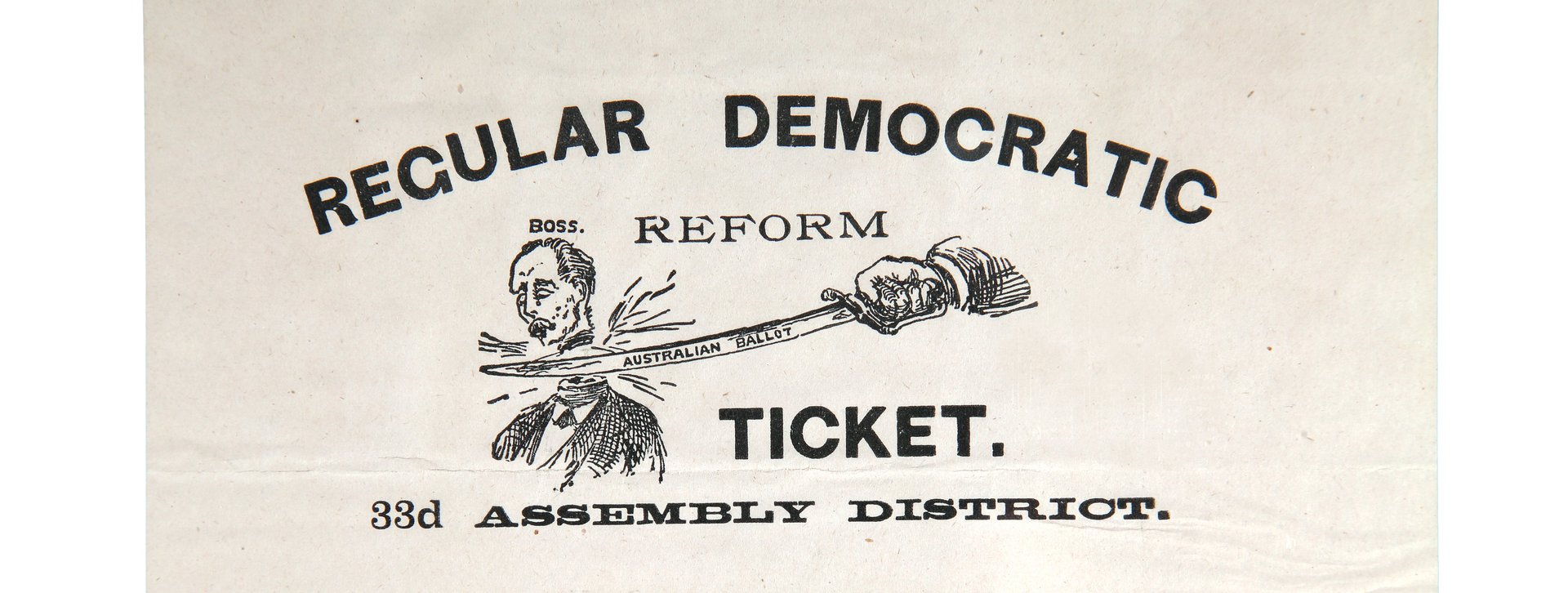

The ballots also show the democratic process reflecting on itself through the ballot. Notably, voting wasn’t secret in early US elections—in fact, it was considered dishonorable to try and hide one’s vote. When the secret ballot—known as Australian ballot, as it was first used in Australia—made its way to the US in the 1880s, candidates celebrated on their 1890s ticket (sometimes graphically) the effect it would have on supposedly corrupt party bosses:

What appeared on ballots changed too, Cheng said: As the democracy expanded, more offices became subject to election, rather than appointment, making voting more common for a variety of roles. If the ballots can be seen as a tangible connection between the government and its electorate, their evolution shows how dramatically the electorate has changed—as well as how different its relationship to the government has become.

An evolving technology

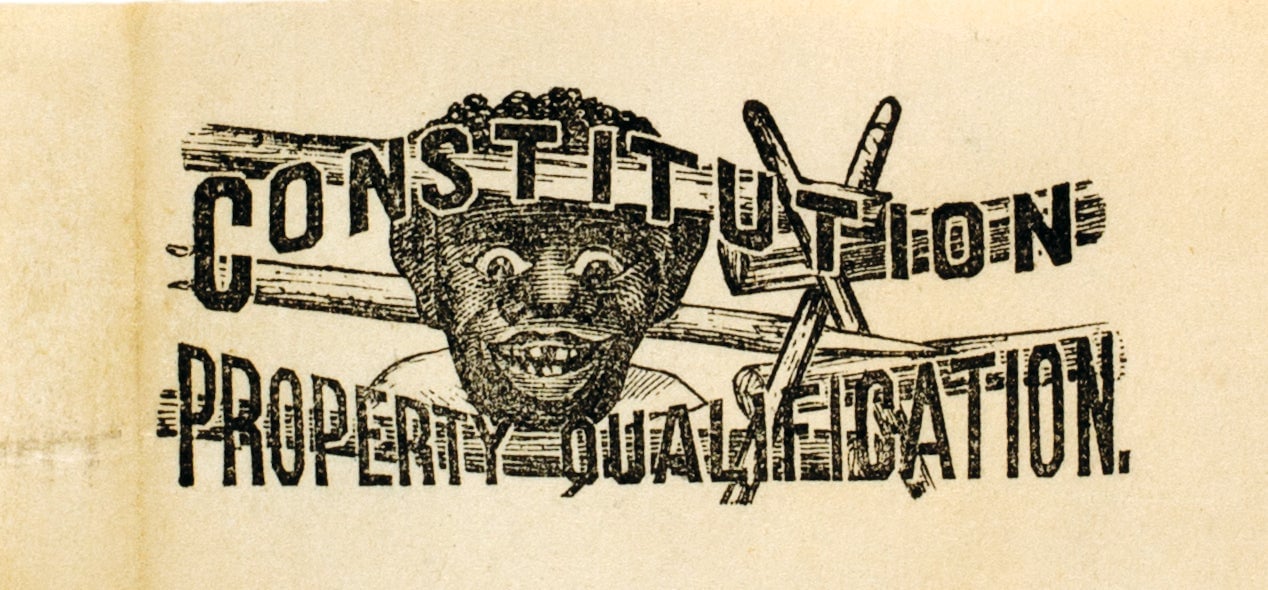

The changes in tickets and ballots are also a representation of the history of printing, typography, design, and their respective technologies.

“You see the rise and availability of inks that are in color, because of refinement to the way that ink production is made,” Cheng, who is a founding partner of design firm MGMT., told Quartz, “or the introduction of letterpress and chromolithography.”

Ballots and tickets had to be distinctive for two reasons: Because they would be more memorable for the voter and, less officially, because prior to secret voting, when ballots were placed in envelopes, party representatives wanted to recognize the ticket from a distance.

“It is a beautiful reflection of what was happening in the graphic design world, as well as paper availability: It used to be harder to get when it was made of linen, but then when they switched to wood pulp it became a lot easier to access, so suddenly everyone was printing tickets much faster and cheaper,” Cheng says, which also reduced the financial barrier to access to running for office.

Some of the ballots and tickets featured in the book sure are outstanding visual and typography feats, such as this 1864 ballot:

A distinctive design was also a way to distinguish the ballots for those who were illiterate or had low levels of literacy. Progressively, it gave space to more standardized functional design, highlighting a change of preoccupation: Fairness, secrecy, and functionality became more important, while as the population became more literate and aware of their rights (including the freedom of voting their conscience), being distinctive was less important.

A fair vote

Like the democracy they helped build, ballots—their design and technology—have been improving since inception, and are far from perfect, still. Jammed machines, wrongful recording, and confusing designs persist, as do widespread attempts to influence elections, suppress voters, and manipulate districts in order to diminish the electoral power of certain communities.

None of it is new. The attempts to use tickets and ballots to confuse voters, or make up votes are as old as the election, says Cheng, and in many cases rather entertaining. The lack of standardization made it easy to commit fraud, since tickets didn’t need to respect a specific format to be valid.

Initially it was the party’s, or candidate’s, responsibility to provide the pre-printed tickets to the voters at the polls, without much oversight, which meant that last-minute changes to candidates, even unbeknownst to the voter, were simple to make, and frequent. Sometimes, voters were even asked by candidates to correct the ballot they had received through “pasters”—small strips of paper with the preferred candidate’s name to glue onto a ballot.

Other creative ways to get more votes was for candidates or parties to print their tickets on very thin paper, so that it looked like only one ballot had been cast, but many thin sheets of paper would multiply in the box, or tapeworm ballot: minuscule sheets of paper easy to sneak into the ballot box.

Still, there and even more now, the actual danger in these kind of inventive frauds was relatively small. “While the tales of voter fraud are quite delightful, like the tales that I found of men shaving off part of their facial hair so that they could vote multiple times,” Cheng said, “it wasn’t rampant.”

It is another type of design that is more dangerous when it comes to fair voting: that of the election itself. Systematic attempts to disenfranchise and suppress voters—things as simple as polling times, or as structural as voter ID laws—are far more dangerous, and always have been, than the creativity of a few determined fraudsters.