A history of American anti-immigrant bias, starting with Benjamin Franklin’s hatred of the Germans

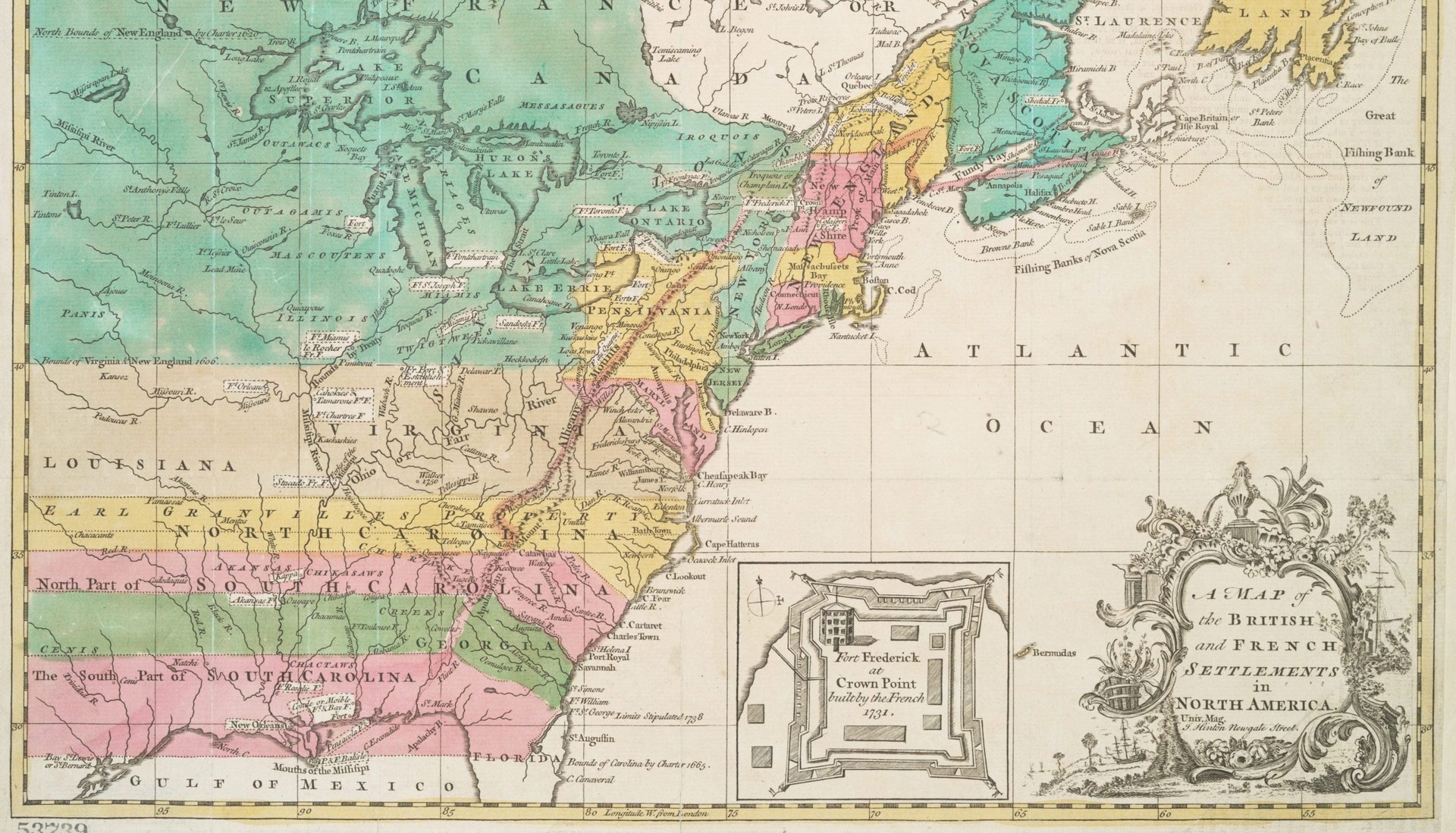

In the 1750s, the United States of America was not yet a country, but its trouble with immigrants already had begun.

In the 1750s, the United States of America was not yet a country, but its trouble with immigrants already had begun.

People of non-WASP (white Anglo-Saxon Protestant) descent were crossing the ocean to start new lives in the new world, and earlier Colonial settlers were none too happy about it. Among them, with ferocious conviction, was Benjamin Franklin, noted inventor, eventual American founding father—and hater of Germans.

In writings from that decade, Franklin shared his concerns about the Germans:

They weren’t as smart as the people already living in the colonies.

“Those who come hither are generally of the most ignorant Stupid Sort of their own Nation.”

They were unable to adapt to the local values.

“Not being used to Liberty, they know not how to make a modest use of it.”

They were endangering New England’s whiteness.

“[T]he Spaniards, Italians, French, Russians and Swedes, are generally of what we call a swarthy Complexion; as are the Germans also, the Saxons only excepted.”

In short, they were not to be liberally admitted to Pennsylvania, because as Franklin argued, “Why should Pennsylvania, founded by the English, become a Colony of Aliens, who will shortly be so numerous as to Germanize us instead of our Anglifying them, and will never adopt our Language or Customs, any more than they can acquire our Complexion.”

To be sure, Franklin, like most other American leaders after him, acknowledged the importance of immigration as a source of growth, and so he didn’t declare himself against German immigration—just in favor of controls on it. “I say I am not against the Admission of Germans in general, for they have their Virtues, their industry and frugality is exemplary,” he wrote, “they are excellent husbandmen and contribute greatly to the improvement of a Country.”

Tu quoque, Hamilton!

Even Alexander Hamilton, an immigrant himself, had his doubts. The country’s first Treasury secretary—currently portrayed in Lin-Manuel Miranda’s award-winning musical Hamilton, where the lyric “Immigrants, we get the job done,” is a reliable applause line—supported John Adams’ 1798 Alien and Sedition Acts, which increased the US residency requirements for US citizenship from five years to 14 years (it’s back down to five now) and allowed the president to forcefully deport immigrants.

In his papers, Hamilton wrote of the dangers of letting aliens into the country, arguing, “The influx of foreigners must, therefore, tend to produce a heterogeneous compound; to change and corrupt the national spirit; to complicate and confound public opinion; to introduce foreign propensities.” Immigrants, they get the job done indeed.

To support his view, Hamilton pointed to a precedent in which being open to foreigners was detrimental: the extermination of native Americans. “Perhaps a lesson is here taught which ought not to be despised,” he said of the friendliness they initially showed to the settlers.

Thomas Jefferson, too, despite believing in emigration as a fundamental right, wasn’t too keen on the Germans, whom he apparently saw as setting a bad example for other immigrants. “As to other foreigners it is thought better to discourage their settling together in large masses,” he wrote, “wherein, as in our German settlements, they preserve for a long time their own languages, habits, and principles of government.”

With all of that as backdrop, it’s no surprise that immigration remains a controversial issue—in a country almost entirely built on the backs of immigrants.

Immigrants are great; just, maybe not a lot of them

The only consistent statistical recording of attitudes towards immigration in the US in the modern era is the answer to a survey question by research company Gallup. Since 1965, Americans have been asked: “In your view, should immigration be kept at its present level, increased, or decreased?”

The majority of respondents has always said to either keep the level or decrease. Only since 1999 have 10% or more of the respondents in a given sample started speaking of increasing immigration.

Karthick Ramakrishnan,a professor of public policy and political science at the University of California, Riverside, whose recent book Framing Immigrants explores the discourse about immigration in America, says there are two main situations in which US attitudes toward immigration change: when the economy is faring badly (although this isn’t always the case; for instance, immigrants weren’t widely blamed for the 2008 recession), and when politicians bring up the issue. According to Ramakrishnan, the politicians are the more influential of the two.

“In American history there has always been a strain of people either scapegoating the other or trying to shut down immigration from places that are seen as un-American or undesirable, even if the reality is far from that,” he says.

First, they came for the Chinese

Since the beginning of the nation, several laws have been passed to contain specific types of immigration, beginning with the Chinese in California.

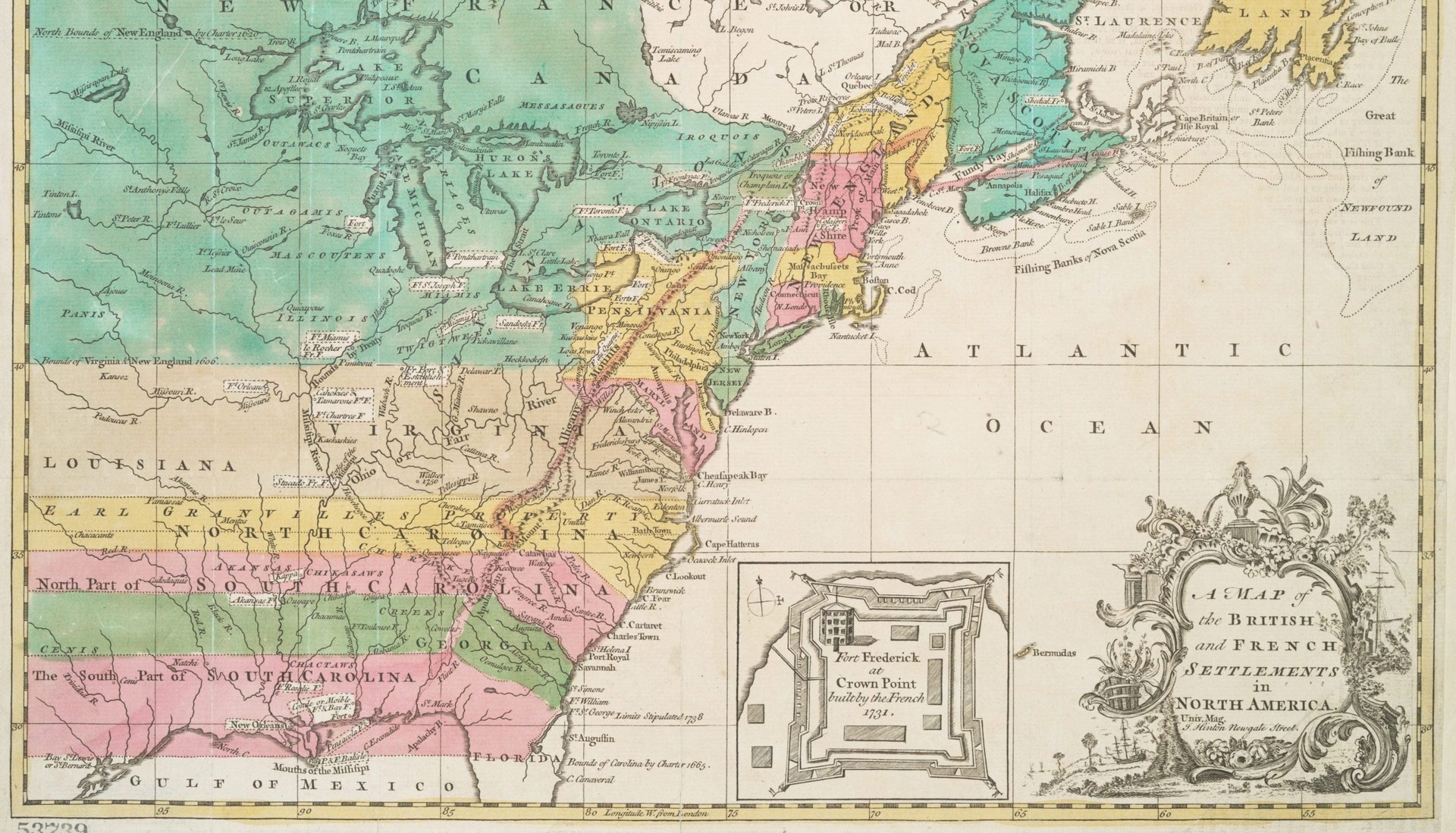

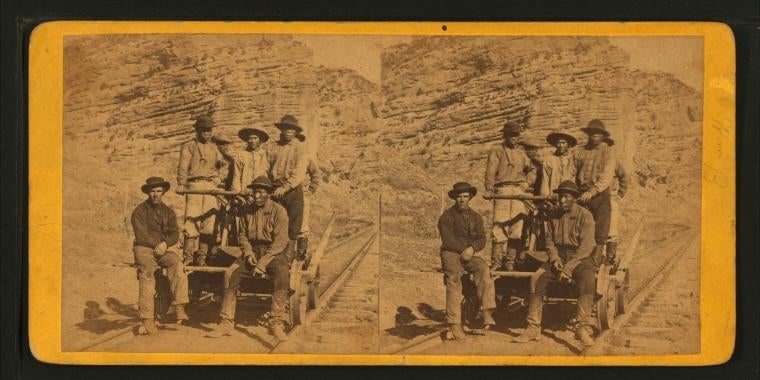

In the 1860s, Chinese immigrants were pretty desirable to the US. With the 1868 Burlingame-Seward treaty, immigration from China was eased, and many Chinese arrived in America to work on the railroad. Many tried to find riches out west—causing what people in California saw as unfair competition in an economy still grappling with the end of the gold rush that had begun a few decades earlier. ”Now California is very progressive on immigration,” says Ramakrishnan, “but in the 1870s California pushed the federal government really hard to pass the Chinese Exclusion Act.” The act, passed in 1882, banned immigration from China and marked the first federal government involvement in the matter of immigration.

Not long after—exactly 100 years ago this week—the government further tightened restrictions on immigration from the east with the Asiatic Barred Zone Act of 1917. The act demanded immigrants pass literacy tests, and excluded certain categories of “undesirables,” including anarchists, paupers, and prostitutes, from seeking immigration. Equally undesirable, according to the act, were citizens of most Asian and Pacific nations, with the exception of Japan and the Philippines.

Make American Great Again, again

In 1924, immigration from Asia was still barred, and quotas were introduced with the aim of limiting immigration of eastern and southern Europeans, particularly Italians, Greeks, and eastern European. Those demanding the quotas, says Ramakrishnan, “wanted America to return to a period when the immigrants came from Germany and northern Europe.”

Immigrants from other areas of Europe presented two orders of problems. First, they were seen as non-assimilating and holding threatening views that undermined the American way of life, such as being pro-labor, or socialist; second, and perhaps even worse, “they were not considered completely white,” Ramakrishnan says.

Being white was, at the time, a key to US citizenship. People of Asian descent, for instance, were forbidden from citizenship because of their complexion. In 1922, the limits of what it meant to be white were tested by Takao Ozawa and Takuji Yamashita, two Japanese Americans whose naturalization cases were brought up to the Supreme Court, with the petition resting on the fact that Japanese people were white skinned. The court ruled against both petitioners on the same day, ruling that “white person” was a categorization that could only apply to people who were Caucasian.

The following year, when Bhagat Singh Thind, a Sikh man, applied for naturalization on the basis that like many Europeans, Northern Indians were Aryans, and hence of Caucasian race, the Supreme Court struck his case down, too, arguing that he didn’t fit the “common understanding” of being Caucasian.

Oh, right, the Mexicans

Interestingly, for a long time, restrictions on citizenships didn’t apply to Mexicans. With the Great Depression, however, and the scarcity of resources that followed, the idea that Mexicans were competing for already rare jobs became prevalent, and between 1929 and 1944, up to 2 million of them were targets of so-called “repatriations.” Effectively, they were the chosen scapegoats of the moment, raided and either deported or scared to the point of leaving the country by themselves, regardless of whether they held US citizenship.

Francisco Balderrama, a California State University historian who wrote about the mass deportation, told NPR that “whether they were American citizens, or whether they were Mexican nationals, in the American mind—that is, in the mind of government officials, in the mind of industry leaders—they’re all Mexicans. So ship them home.”

War enemies and refugees alike

In 1942, after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor prompted US involvement in World War II, then-president Franklin D. Roosevelt ordered the internment of Japanese Americans, who were sent to live in areas designated by the US military. People of Japanese origin were kept in internment camps or relocation camps, under the suspicion that they might be sympathizing with the enemy. Nearly 70% of the 130,000 detainees were American citizens. A small number of US citizens of Italian and German origins were detained, too.

At the same time, Americans weren’t particularly welcoming to the primary victims of their main enemy’s fury—Jewish refugees from Nazi persecution in Europe were not easily offered asylum to the US, and they were often turned around. A historic case is that of the St. Louis, a ship full of Jewish asylum seekers. It was not accepted by the US, and its passengers ended up, for the most part, dying in Nazi concentration camps.

It wouldn’t be the last time the US aligned itself against a foreign enemy (the Nazis then, the Islamic State today) without it translating into broad acceptance of the refugees driven from their homes by that enemy—with the refugees, then as now, suspected of posing a threat to the country’s safety.

A nation of immigrants

American immigration was based on a quota system that privileged Caucasians and western Europeans, until it was scrapped in 1965. This followed then-president John F. Kennedy’s vision of America as a “nation of immigrants,” which he laid out before his election, in 1958. It successfully established a new rhetoric that, for many, reframed the identity of America. For decades, no one group was specifically targeted or marginalized—until right after 9/11, when male non-citizens from two dozen Arab or Muslim-majority countries became subject to special restrictions while in the US.

The 9/11 response made it all the more difficult for then-president George W. Bush to amass support for the comprehensive immigration reform he in fact favored, and set the stage for today’s political turmoil over US border control.

Ramakrishnan looked at how the latest wave of xenophobia took over America in another of of his books, The New Immigration Federalism. “States like Arizona and Georgia started pushing anti-immigration policies after 9/11,” says Ramakrishnan, “and certain politicians tried to exploit the immigration issue as a way to push back against the Bush administration.”

This current within the Republican party started both creating and riding an anti-immigration sentiment. (Even now, this wing of the party propagates the idea that illegal immigration from Mexico is out of control—while, in fact, it’s at historically low levels.)

“In many ways we see the fruits of this today; even before the Tea Party you had this anti-immigrant push within the Republican party,” says Ramakrishnan, “and now they are in power.”