Vladimir Putin’s popularity at home is soaring, but it might not last

Wrong-footed by the speed with which Crimea slipped from Ukraine’s control, Western diplomats are reassessing what they thought they knew about Vladimir Putin. The Russian president’s unflinching support of the peninsula’s referendum on joining Russia caught many by surprise. As Quartz’s Steve LeVine explains, the conventional wisdom about Putin’s motives proved misguided, to say the least:

Wrong-footed by the speed with which Crimea slipped from Ukraine’s control, Western diplomats are reassessing what they thought they knew about Vladimir Putin. The Russian president’s unflinching support of the peninsula’s referendum on joining Russia caught many by surprise. As Quartz’s Steve LeVine explains, the conventional wisdom about Putin’s motives proved misguided, to say the least:

He was understood in diplomatic capitals as an intelligent ruffian with whom, when it really counted, you could usually do business. A military assault on Ukraine seemed well outside the margins. But then he invaded anyway.

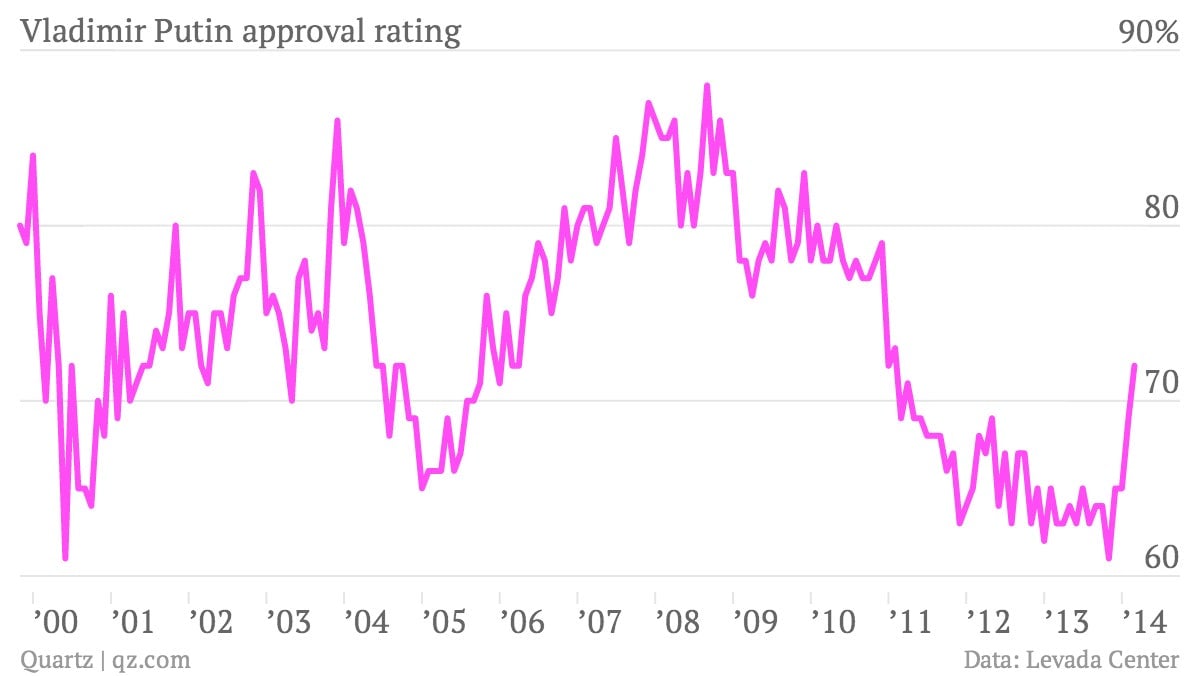

Putin is not the same leader as the one who first came to power as president in 1999. He is “less pragmatic, higher-risk, and much more likely than his progenitor to act out Russian glory in its imperial prime,” LeVine writes. And for all the angst this is causing in the West, the act is playing well for Putin at home. According to the latest survey by the Levada Center (in Russian), an independent pollster, the president’s approval rating is the highest it’s been during his current term, which began when he switched back to president in May 2012 after a four-year term as prime minister.

In fact, shortly before the unrest in Ukraine broke out late last year, Putin’s approval ratings were languishing near all-time lows. (Although, at around 60%, “low” is a relative concept.) Now, Putin’s approval rating has climbed to a heady 72%, a level not seen since early 2011, before the rancorous run-up to a disputed legislative election broke into popular unrest in Moscow.

In a separate poll (in Russian), the Levada Center found that most Russians believe that the domestic media’s coverage of the Ukraine crisis is credible, that radical Ukrainian nationals are behind the turmoil in Crimea, and that deploying Russian troops in Ukraine would be justified to protect the Russian-speaking population. Although Putin’s ratings still have a ways to climb before they reach previous highs, it is telling that his loftiest ratings came in 2008, not long after the invasion of restive Russian-speaking regions in Georgia.

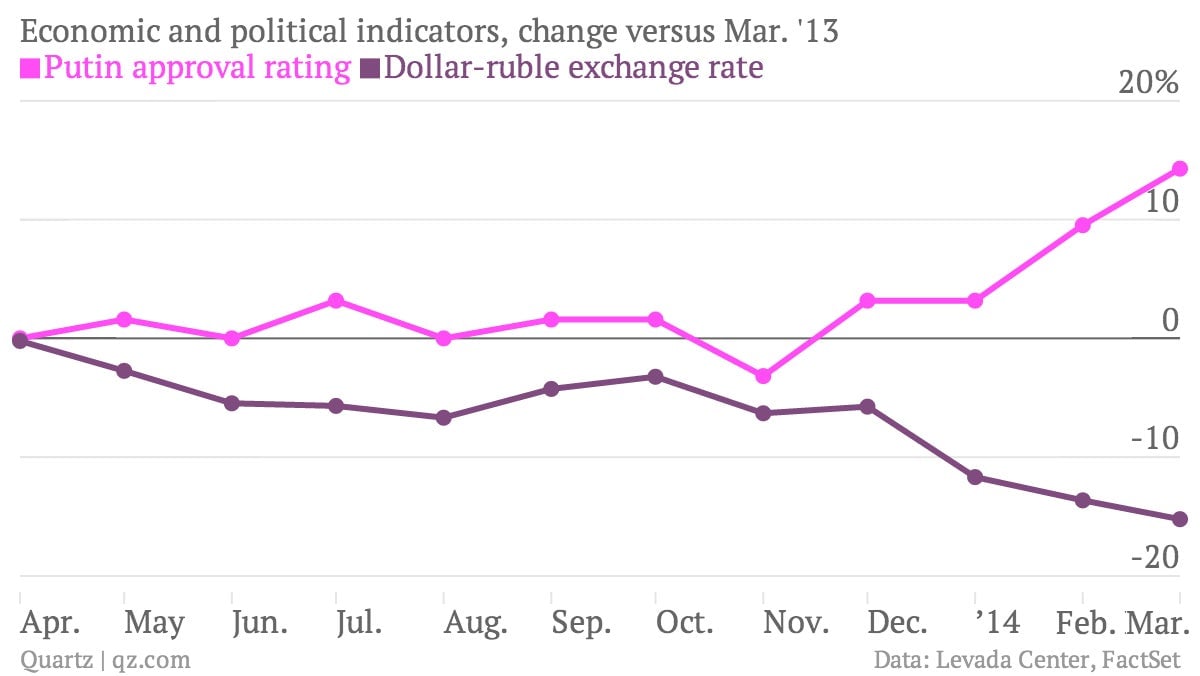

But it is also important to note that the Georgia-driven surge in then-prime minister Putin’s ratings quickly faded, as the global financial crisis hit Russia hard. The rather tepid recovery now risks being derailed by the crisis in Ukraine, with markets shunning a variety of Russian assets in response to the uncertainty. The rise in Putin’s popularity is mirrored almost perfectly by the decline in indicators like the value of the ruble:

It will be hard to keep this up. The boost that Putin gets from supporting the separatists in Crimea, and possibly others in Ukraine’s many Russian-speaking regions, may fizzle out if the economic repercussions at home are grave enough. After all, over time Russian citizens will value what’s in their wallets more than abstract geopolitical goals abroad. As the famous political mantra goes, “это экономика, глупый.”