The future of robotics is soft and squishy

Soft robotics is ready to enter the spotlight. These robots are built with soft materials like silicone and powered by the flow of fluids. This allows for unique kinds of movement, with the automatons often taking locomotive cues from the animal kingdom. As recently as 2010, when the video below was made, soft robots weren’t considered a field of study in their own right. But this month, a peer-reviewed journal, Soft Robotics, was launched just for them:

Soft robotics is ready to enter the spotlight. These robots are built with soft materials like silicone and powered by the flow of fluids. This allows for unique kinds of movement, with the automatons often taking locomotive cues from the animal kingdom. As recently as 2010, when the video below was made, soft robots weren’t considered a field of study in their own right. But this month, a peer-reviewed journal, Soft Robotics, was launched just for them:

These robots have unique applications: Unlike a hard robot, a soft one can run into a human or animal (or wall) without causing much harm to either party. Their flexibility also makes them adept at tasks in tight, irregular spaces like the rubble of a collapsed building or an unexplored cave. For robots that move by creeping and crawling, hitting surfaces can actually be a good thing: It gives them purchase to move around the environment.

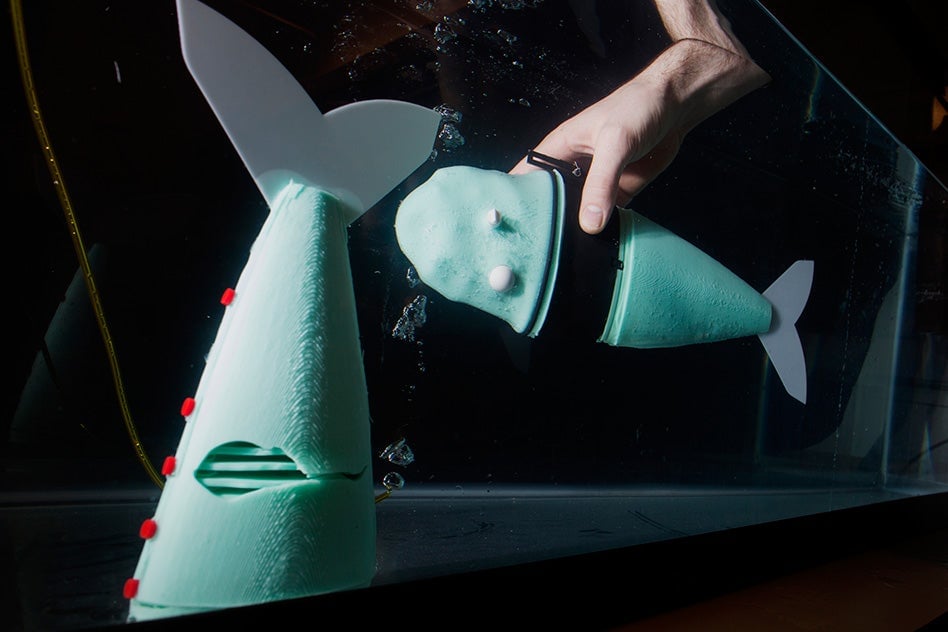

In one of SoRo’s first papers, MIT researchers report on the soft robotic fish they’ve developed. Because the fish can bend continuously—it has no joints and is controlled by the flow of carbon dioxide pumped through channels in its tail—it can achieve a range of motion that would be impossible for a hard robot, researchers said. The current model can perform about 20 or 30 maneuvers before running out of gas. But the next version will pump water into its channels, allowing it to operate for about 30 minutes continuously.

The fish is just a proof of concept, and probably won’t be going deep-sea diving any time soon. But researchers imagine that it might be deployed with schools of real fish to observe their behavior. And more soft robots are on the horizon. A Boston-based startup is working to replace surgical robots with softer, safer alternatives that won’t risk tearing your organs. And researchers working under DARPA’s Maximum Mobility and Manipulation initiative, which aims to develop nimbler robots for military use, have turned to soft robotics, too: