India has the world’s biggest cannabis industry that doesn’t exist yet

In India, cannabis is everywhere.

In India, cannabis is everywhere.

Hundreds of varieties of the three types of cannabis—Sativa, Indica and Ruderalis—grow wild over the Indian subcontinent, cropping up lush alongside highways or city parks, taking over like, well, a weed.

Vijaya, as cannabis is known in the ancient Hindu Vedas, is part of the country’s mythology, history, and festive traditions. There is only one aspect of Indian society it isn’t yet part of: industry.

In countries around the world, cannabis is rapidly becoming a booming business: After long, futile attempts at prohibition, governments are finally realizing its medical and economic potential. Countries like Canada and South Africa have legalized cannabis for many uses, including recreational. Others, like most nations in Latin America, and parts of Australia have decriminalized it—cannabis isn’t legal, but the use and limited possession of it aren’t persecuted. In the US, some states have legalized cannabis for recreational use, and others have decriminalized it.

Now Indian entrepreneurs, sensing boundless opportunities, are pushing for similar reforms and working with individual states to update old laws.

In India, cannabis is illegal for recreational use under a law passed in 1985 after prolonged pressure by the international community, and particularly the US. According to the Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances (NDPS) Act, the possession of even small quantities of marijuana can be punished with a fine of up to Rs 10,000 ($130) or up to a year in prison.

Beginning in 2013, startups and business ventures have worked with the government to open up an industry and legal production, but though they were able to make some progress, there is still virtually no legal cannabis grown in India. Despite its abundance, at the moment India is all but absent from the global cannabis business.

“It’s like: water, water everywhere, and not a drop to drink,” Jahan Preston Jamas, a co-founder and director of strategy at Boheco (Bombay Hemp Company), one of the companies selling hemp and cannabinoid-based wellness products in India, told Quartz.

The situation is actually even more paradoxical: Although there is no legally grown cannabis in India, every year tons of cannabis is sold through government channels. According to Boheco’s estimates, 240 tons are collected in the state of Madhya Pradesh alone.

One plant, two legal statuses

While smoking cannabis is illegal in India, the plant itself isn’t—not always, anyway. Cannabis is intertwined with the culture of India in many levels, and particularly with religion and traditional medicine.

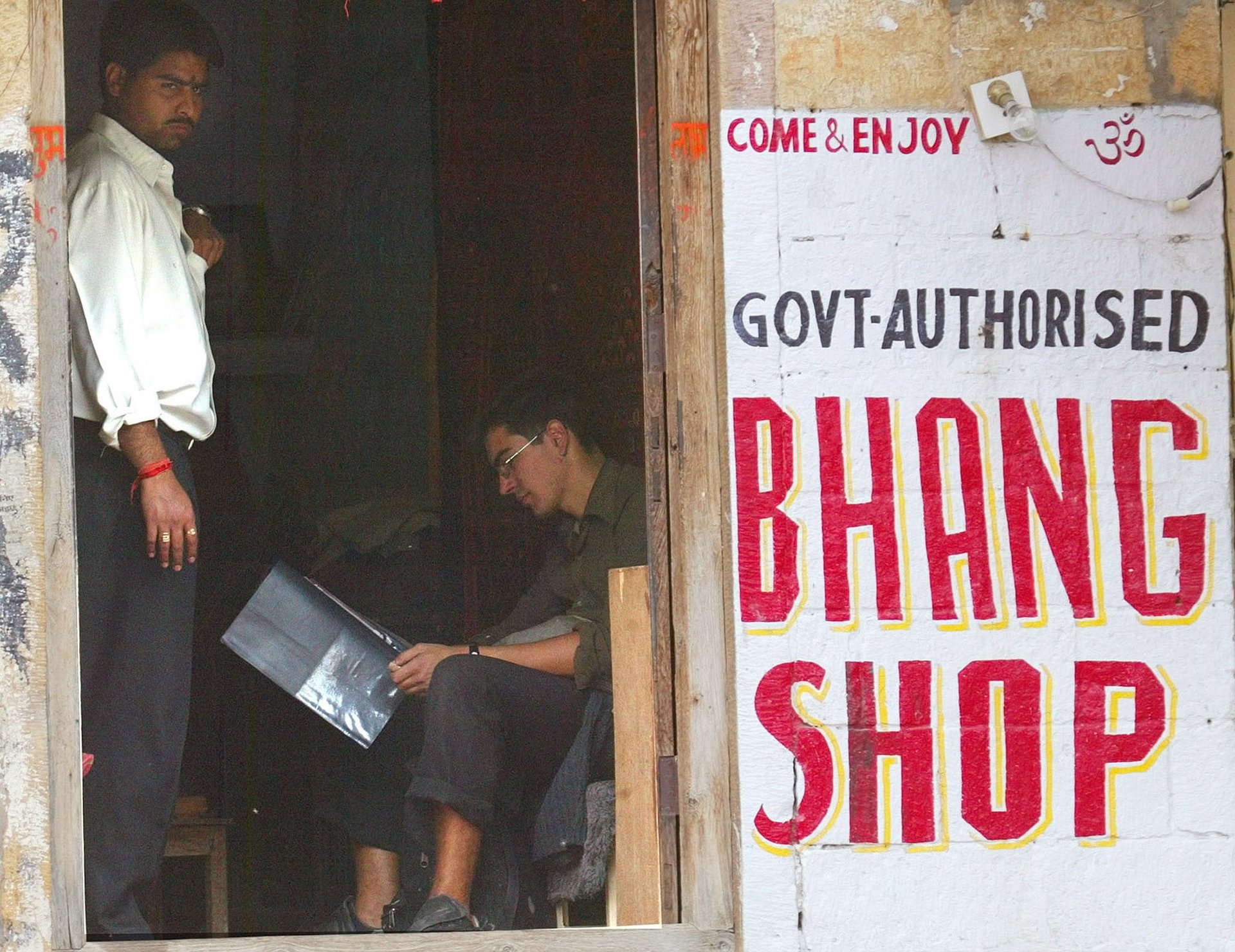

Cannabis is sacred to Hinduism, and has been for millennia. It is, for instance, the favorite food of Lord Shiva, the Hindu god of destruction. According to a common Hindu legend, he ate it after spending the night outside following a fight with his family, and found himself reinvigorated. The country’s most important Hindu religious sites have special permission to sell bhang—that is, cannabis leaves or seeds—as an essential part of several religious rituals, during which it is either smoked or added to a drink.

Festivals, too, can involve the use of cannabis: The spring celebration of Holi, for instance, often sees ordinary Indians—who wouldn’t otherwise consider themselves overly religious, or habitual cannabis consumers—have drinks with added bhang.

The medicinal powers of cannabis, too, have been known to India for millennia. Its calming properties, for instance, are described in detail in the Vedas, and used in traditional medicine, or ayurveda. The ministry of AYUSH (Ayurveda, Yoga & Naturopathy, Unani, Siddha and Homeopathy) allows licensed practitioners as well as medical doctors to prescribe cannabis extract. However it must be administered in compounds including other elements, as cannabis by itself is classified as a toxic, though medically important, substance.

This is why it is available to retailers who hold a license to sell it in certain sacred locations, such as Varanasi, Rishikesh, or Pushkar, allowing them to add it to drinks or sell it for medical purposes. However, the fruit and flower of cannabis (ganja) remain illegal. While hired government contractors can gather the leaves and seeds that are growing wildly, farming the plants remains off limits.

The business of bhang

Before January 2013, when Jamas started Boheco together with six other business school classmates (Avnish Pandya, Chirag Tekchandaney, Delzaad Deolaliwala, Sumit Shah, Yash Kotak, and Sanvar Oberoi), no companies in India had tried to tap into the enormous potential of India’s cannabis market.

Beyond the natural habitat for cannabis, and the traditional familiarity with its properties, India’s cities have among the highest rates of cannabis consumption in the world. Even by more conservative estimates, the market is still enormous. A 2019 report from India’s Ministry of Social Justice found 31 million Indians said they had used cannabis within a year, of which 22 million consumed bhang and only about 9 million ganja.

It is a drop in the ocean of India’s 1.3 billion population, but a significant market to start from nonetheless, in absolute numbers. Given India’s 600 million-person strong, young middle class, and the wide familiarity and acceptance of cannabis, the potential for wellness and medical products as well as in recreational use is massive.

According to the current estimates, it might take five to 10 years to get to production in the order of thousands of acres—large enough to have a significant business impact. Over the next five years, Boheco estimates, the economic opportunity for industrial hemp and medical cannabis—both Ayurvedic as well as pharmaceutical—would be around $500 million to $750 million.

Yet it was something else that initially enticed Boheco’s founders toward the business: the agricultural potential of hemp, the non-psychotropic varieties of cannabis with many uses. Agriculture is by far the largest sector in India when it comes to employment, with 60% of the population working in farming. But the sector’s contribution to the GDP is much smaller—just 15%. Boheco’s founder saw in cannabis a crop with great agricultural potential: Native, resilient, and with low water requirements, it could bring great returns even to smaller farmers. “A crop like hemp has immense strategic value for the Indian ecosystem,” says Jamas.

This is especially true when comparing the qualities of cannabis grown for hemp fibers to those of cotton: Hemp grows in about a third of the time it takes cotton, it doesn’t require pesticides, and not nearly as much water.

“The idea was, for lack of a better word, make agriculture sexy enough so that it’s going to attract a lot more people,” Yash Kotak, one of the founders, told Quartz. “And what better crop than hemp for cannabis to do that?”

From old tradition to new business

“We weren’t just starting a new company,” Kotak remembers of launching Boheco. “There was a whole new industry that we were starting out.” Building the industry from scratch required efforts in three areas: legal framing; research; commercialization.

Boheco and other similar companies now sell a range of products made of cannabis—both textiles and wellness products—though their raw material isn’t yet from grown hemp but from fiber harvested from plants growing wild. Earlier this year, one such company even opened an ayurvedic clinic focused on CBD-based treatments.

The legal scenario, too, is patchwork.The government allows states to set their own regulations with regard to industrial and medical cannabis. Uttarakhand, in the north of the country, was the first state to allow commercial cultivation of hemp in 2018, followed by Uttar Pradesh, India’s most populous state. A few other states are allowing cannabis for industrial and medical purposes—and about half of India’s 28 states are at some stage of considering legalization of cannabis cultivation.

Using the US as a template, states have allowed for production of cannabis with a maximum of 0.3% THC (the main psychoactive compound in cannabis) content. However, most of the cannabis growing wildly in India contains higher levels, and so far research, including several projects in partnership with the government, has focused on developing a hybrid that would be able to produce lower levels of THC irrespective of the environmental conditions it is being grown in.

Getting this right is essential to protect farmers, Jamas explains: If a variety were to develop a higher than allowed level of THC during cultivation, the farmer would have to burn it, losing the investment, as well as the time it would take to switch to another crop.

Not everyone is convinced things are moving fast enough, however. Local companies need to push regulators and researchers to open up the market, says Priya Mishra, a cannabis activist who goes by the name of Hempvati . Based in Old Manali, Himachal Pradesh—a longtime destination for international tourists looking for cheap and easily available weed, despite the legal obstacles—she works to promote the medical benefits of cannabis, says

This, she says, allows foreign investors and researchers to take advantage of the variety of cannabis growing India and use it to patent their own medical innovations without giving local producers enough of an opportunity to make profit.

“It’s like they are introducing the iPhone 3 in India while the rest of the world has the iPhone 11,” Mishra told Quartz.

But things seem to be moving, and even the country’s infamous red tape might be a little less of an obstacle than usual. Cannabis legalization has the support of the main political parties, says Jamas, and even bureaucrats who might otherwise be resistant to innovations are familiar with the potential and benefits of cannabis. Because cannabis was completely legal and part of the culture in many areas of the country prior to 1985, many have recollections of using it as a medical remedy, for instance.

“Some of the [legislators] have spoken about traditions where they used to sit in December with their mothers and fathers and crush the bhang seed to make chutney and sit and eat together because it would keep them warm in winter,” Jamas said, “so there’s a lot of ubiquitousness and sort of commonality associated with it.”

Still, while the country has all the potential of being a global leader in cannabis production, that day is still far off. “I would say that where Canada was say about 10-15 years ago with this crop—India is at that juncture right now,” Kotak said. It took years of research and business development for Canada’s cannabis industry to reach its $7 billion sales in 2019—and it will be the same for India, he said.

“We can do this well, or we can do this fast” Jamas says, “but we can’t do both.”