The whole thing is there, you see. The world of space and time, and matter and energy, the world of creation and destruction, the world of psychology…We (the West) don’t have anything remotely approaching such a comprehensive symbol, which is both cosmic and psychological, and spiritual.

The idea of dancing before a corpse wasn’t new to me. Yet, discovering a god who could be the source of a cool t-shirt slogan in it was stunning.

Even decades of tripping on koothu, a dance form popular among cinema-lovers of southern India, had not prepared me for it. Yet, here I was one September day in 2018, searching for hints of lord Nataraja, the mythical fountainhead of most Indian classical dance forms, in this most unruly of performances called Saavukoothu, “the death dance.”

A street dance practised by a section of Tamils while accompanying the departed to their final resting place, Saavukoothu doesn’t demand any of the refinement of Indian classical dance traditions like Bharatanatyam or Kathak. There is only one rule: Let go completely.

I’d been reading up on Nataraja, the dancing version of the feral Hindu god Shiva, for weeks, hoping to trace his origins and evolution over a period of nearly five millennia. The tranquil-yet-ferocious one is said to reside on Mount Kailasa, now in the Tibetan Himalayas, according to Hindu mythology. The third pillar of the pantheon—Brahma and Vishnu being the others—is believed to be easy to please, yet supremely destructive.

My search took me to Chennai, the capital of the southern Indian state of Tamil Nadu and home to perhaps one of the greatest collections of ancient Nataraja statues under one roof. It is at the Government Museum in the city’s Egmore locality that one expert hinted that even something as raw as Saavukoothu could be linked to Shiva. Curiosity kindled, I began visiting the city’s many crematoria.

At one such facility, I met the wiry Rajkumar, head of a group of percussion artistes who lead Saavukoothu processions. For the 38-year-old, who uses only his first name, giving rhythm to “death dancers” has been a family tradition. But he was too modest to hold forth on the subject itself. “My grandpa could have given you more details. Unfortunately, he’s no more. I am still a novice when it comes to the porul (crux) of koothu,” Rajkumar told me. Instead, he directed me to Ragothaman, a priest at a local Shiva temple.

A trained engineer, the priest said Savukoothu is symbolic of Shiva’s primordial performance. The dead are believed to be finally joining “Koothu Perumal,” the lord of dance in the Tamil language, which is one of Shiva’s many epithets. Over centuries, the matted-haired, animal-skin-wearing, hash-smoking god has evolved into many things, including a hermaphrodite, for many people.

Such has been his transformation that this dweller of cremation grounds—Shiva is often imagined as covered in ash from funeral pyres—today can be found even on the grounds of the European Organization for Nuclear Research (CERN) campus in Switzerland, where, in his Nataraja form, he symbolises the high-energy collisions of particle physics.

In the most recognisable Nataraja version, he is seen dancing in sheer abandon, hair locks wildly swaying and his limbs placed in broad symmetry. The lord stands beautifully balanced on his right leg, often trampling a tiny figurine. His entire persona is framed by a circle of flames.

In a furiously and incessantly transforming world, the Nataraja’s message, “Keep calm and move on,” may be among the few relevant spiritual anchors of our times.

The blissful Nataraja, dancing the world into being

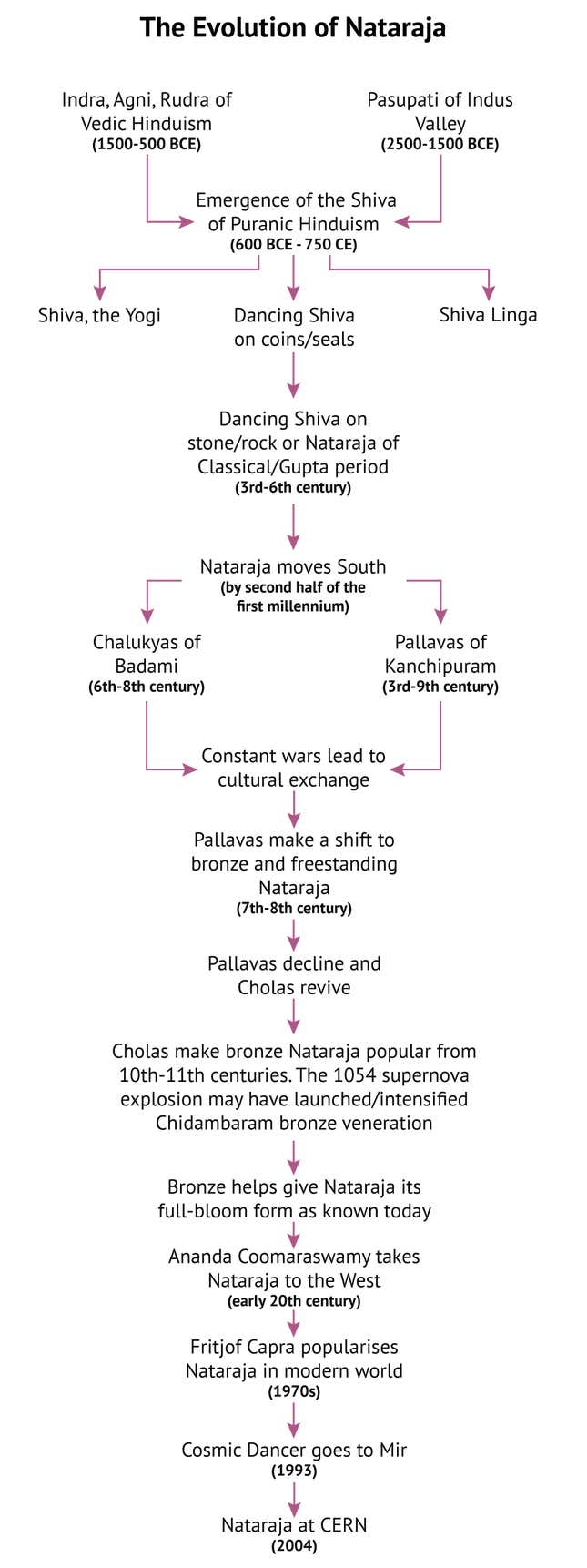

The origins of Nataraja, and of the Hindu god Shiva himself, lie deep in ancient history. However, the form we recognise most today may be said to have culminated around the 9th or 10th century in southern India: The Ananda Tandava, or blissful dance.

In it, Shiva is in the Bhujangatrasita karana pose, translating from Sanskrit to “frightened by a snake,” with his left leg held across his body at hip level. He is said to be creating and destroying existence both at once, yet offering the escape hatch from this constant chaos. Finally, he is also revealing the key to that escape hatch, which is to subdue ignorance.

The following are the five most important elements, indicating the Panchakritya, or five key acts of the Nataraja.

Srishti or creation: The Nataraja’s rear left arm carries the hourglass-shaped drum, damuru, the vibrations of which create the universe. Some conflate this with the Big Bang of cosmic creation (more on this later).

Samhara or destruction: The raised rear right hand carries the fire that atrophies matter, only for regeneration. It is the fire of transformation and not destruction. It implies constant change, echoing the Buddhist precept of “There’s no being, only becoming.”

Sthithi or maintenance/protection: The open palm of the forehand indicates his assurance: “There is nothing to fear about the constant cosmic overhaul. Change is normal and I’m here to protect you.”

Tirobhava or concealment: The hidden lower-left palm pointing downwards says he’s the creator of maya, illusion or the veil of ignorance.

Anugraha or blessing or liberation: The raised left foot, combined with the closed hand, signifies the option available before the seeker: moksha or liberation from ignorance and, by implication, from the cycle of birth and death.

A few more elements complement the idea of Panchakritya. These are:

Muyalaka or Apasmara: This dwarf demon at the Nataraja’s feet represents the evils of ignorance and ego, to be trampled upon if one must rise to a higher plane of self-actualisation.

Circle of fire: The frame around Nataraja is the visual manifestation of maya as experienced through the cycle of birth and death.

If all this seems esoteric, wait till we get to modern physics’ connection to the Nataraja. But before that, we must trace the more earthy origins of the mighty one.

The people’s yogi meets the warrior gods

The Indus Valley civilisation’s script has not been deciphered. A lot of the culture’s social, religious, and economic aspects remains a mystery.

We do know, however, that the region of northwest India, in River Indus’s basin, began urbanising around 3300 BCE and declining by 1500 BCE. Its natives had their own religious universe, but most of their gods, goddesses, and rituals are lost and forgotten. Yet, some seals, tablets, and terracotta figurines found at sites like Mohenjodaro and Harappa tell their tales.

One such tablet, more than 4,000 years old, shows a man, his penis apparently erect (“ithyphallic”), meditating cross-legged in yogic posture. Sporting a double-horned headgear, this icon is surrounded by animals like a tiger, a rhinoceros, and an elephant. This has led archaeologists calling him Pasupati (pasu is animal in Sanskrit, pati is lord. But Sanskrit wasn’t native to Indus Valley).

This mysterious figure is often deemed proto-Shiva.

A dancing god, too, may have existed back then, going by the “the dancing torso of Harappa” figurine. This one also supposedly has an erect phallus. In her book, Siva: The Erotic Ascetic, historian Wendy Doniger writes, “The raised linga (phallus) is the plastic expression of the belief that love and death, ecstasy and asceticism, are basically related.”

By 1500-500 BCE, the Indus Valley Civilisation was in disarray, giving way to the Vedic age. The Vedas, foundational Hindu scriptures, were composed by the nomadic tribes from the central Asian steppes that began flowing into the Indian subcontinent in the first millennium BCE.

Doniger writes that Rig, the first of the four Vedas mentions yogic practices and phallic worship “as characteristic of the enemies...”

On the other hand, the central Asian nomadic tribes had their own religious iconography, often aggressive and martial. For the purpose of charting the possible path these new gods took towards popularity, let us briefly imagine a day in one such tribal settlement.

The men have just returned from battle and are preparing to celebrate victory. As the sun begins to set, a campfire is kindled. The clan huddles up around the fire. Soma, their favourite ritual drink, is generously served. Inebriation, music, dance, songs, and general revelry follow as the best of the performers with graphic makeup take the lead.

They strike ferocious warrior poses and boogie to aggressive drumbeats. The leaping campfire flames and enraptured shrieks are accentuated by the sun’s farewell drama in the sky. Throw in an oracle or two in full reverie. Why wouldn’t the primitive audience be impressed? Such imageries, ritualised and awe-inspiring, are wont to have entered the tribe’s oral tradition: hymns, poetry, and chants.

Somewhere in the region, the Vedas are being composed around this time. In these profound philosophical works, fighting prowess, generosity, creative talent, leadership, and many more such qualities—all aspirational—get attributed to gods. It wouldn’t be surprising if talented performers like the ones from the above tribe turned cultural icons and, perhaps, even gods (Why not, if Elvis Presley can be imagined as an alien and Indian movie stars can be gods?).

Dancing icons like the Maruts, the Ashwins, and the Adityas, were clearly in vogue in the Vedic age. The favourite was probably Indra, who loosely corresponded to ancient Greece’s Zeus.

Vajra (thunder)-wielding Indra, “is the immortal dancer, who, enveloping the earth by his glory, bestows prosperity, as the abode of all treasures,” the late art historian Calambur Sivaramamurti wrote in his 1974 book Nataraja in Art, Thought and Literature. The traits and avatars attributed to Indra by the ancient Hindu texts include:

- Purandara: destroyer of forts or fortified towns

- Sahasraksha: one with a thousand eyes on his body (how he got them is another lustful tale)

- Practitioner of Indrajaala, the art of illusions

- Destroyer of Vritra, the demon of darkness

- Pasupati, lord of all animals (livestock perhaps) or just king

- Husband of Sachi, whose father he slays

By the first millennium CE, south Asia was moving from the Vedic age to the Puranik (350-750 CE), the confluence of cultures brought together the two tributaries of Hinduism: Indus Valley’s “Pasupati” and the warrior gods of the steppe nomads.

This period of transition also marked the rise of Buddhism and Jainism, considerably obscuring the churn from which modern Hinduism began emerging: Vedic deities like Indra, Agni (the god of fire and passion), and Rudra (the enigmatic master of death), lose space to, among others, Vishnu, Brahma, and, most importantly, Shiva.

By this time, Shiva is worshipped in three main forms, all derivatives of older icons:

Shiva, the meditating yogi: Straight from Indus Valley. “Shiva’s horns are retained...in the form of the crescent or horned moon on his head and in his high-piled matted locks,” Doniger writes in her book. “From Indra, Shiva inherits his...adulterous character, from Agni the heat of asceticism and passion, and from Rudra he takes a very common epithet (Rudra), as well as certain dark features.” The third eye on Shiva’s forehead, according to Sivaramamurti, is derived from Indra’s thousand eyes (Sahasraksha).

Linga or phallus: Another feature seemingly inherited from Indus Valley. The Gudimallam linga in the southern Indian state of Andhra Pradesh has an erect phallus on which an image of a standing Shiva is carved, a clear merging of Shiva’s aniconic and anthropomorphic forms. It is considered the earliest known Hindu sculpture (pdf) and is from around the second century BCE.

Nataraja: Dance as part of a divine ritual may have its base in the Indus Valley. However, “mere dance conveys no meaning. Conveying meaning through dance required attributes such as postures and gestures with symbolic elements,” says historian Shrinivas Padigar, a scholar of ancient inscriptions and a retired professor of Karnataka University in Dharwad, in the southern state of Karnataka. “In its ultimate version, Nataraja’s relationship is with the concept of the ‘game or play of Shiva’ throwing the web of illusion and making way for the salvation of beings,” he says.

Poetry in stone

Stone and rock sculptures abruptly came into being in South Asia during the time of the first Indian empire under the Mauryas (322-185 BCE). The phenomenon was perhaps seeded by this dynasty’s close ties to the Hellenistic and Persian worlds.

By the time of the Puranik or classical era, which blossomed under the region’s first Hindu empire of the Guptas (3rd-6th centuries CE), the dancing Shiva had begun to emerge in his most dramatic form. Not surprising, since “drama was the all-inclusive performing artform of classical India..,” historian Abraham Eraly writes in The First Spring: The Golden Age of India.

Some of the most glorious Nataraja sculptures known today were created around this time. This includes the famous ones at Ellora and Elephanta caves in Maharashtra (5th-9th centuries).

About the Elephanta icon, Sivaramamurti writes: “...(it) is probably unsurpassed in the golden age of Indian art. For sheer rhythmic movement, a delicacy of contour line and limpid grace in form and texture, there is nothing to approach this piece. The fact is this is a highly developed sculptural version of the concept of dance.”

The second half of the first millennium CE, however, saw the scene shift decisively to southern India where two warring powers become key to the Nataraja’s story: the Chalukyas of the Deccan (543-757 CE) and the Pallavas (275-897 CE) of the Tamil country, already a bastion of Shiva worship deep south.

Around 642 CE, Pallava emperor Narasimhavarman subdued his most important rival, the Badami Chalukyas (543-757 CE). The latter’s legendary king, Pulakeshin, had humiliated his father, Mahendravarman, in battle some 25 years earlier. Yet, one imagines that Narasimhavarman was in awe of the temples and sculptures in the Chalukyan capital of Badami and other cities of the defeated empire like Pattadakkal in today’s northern Karnataka.

Having travelled more than 600 kilometres northwest from his home on the southeastern coast of India, Narasimhavarman simply couldn’t help borrowing Chalukyan ideas and incorporating them in his father’s magnificent shore city project, Mamallapuram or Mahabalipuram near modern Chennai.

“...culturally what all Narasimhavarman could carry back to be repeated at Mahabalipuram shows that the victor stooped to gather blossoms of culture from the land of (the) vanquished…the frequent inroads of the Chalukyas in Pallava territory and vice-versa have created a permanent record of cultural fusion as we see in sculpture in both areas,” Sivaramamurti writes in his 1955 book Royal Conquests and Cultural Migrations in South India and the Deccan.

Particularly eye-catching was the roughly four feet tall, 18-armed dancing Shiva at the entrance of Cave 1 in Badami. Historian Charles Allen writes “...it is generally considered to be the earliest portrayal of Shiva as Nataraja.” “A second Chalukyan incursion followed in 744, so presumably it was at this time that the concept of Shiva Nataraja migrated south to take root in Pallava country,” Allen writes in his book Coromondel: A Personal History of India.

However, others aren’t sure about this hypothesis. “The idea could have spread to the south...but I doubt Badami is where it began,” says Padigar. Sivaramamurti believes another statue some 700km east of Badami (in modern Andhra Pradesh’s Vijaywada) is “the earliest Nataraja figure in the southern part of India.”

Whichever was his pitstop, Nataraja quickly grew roots in the south and flourished. So much so that he travelled beyond the seas to even southeast Asia, where many south Indian empires expanded.

Some of Shiva’s dancing poses are now codified in classical dance forms like Bharatanatyam, Kucchipudi, and Mohiniyattam. “The variety of postures and hand gestures of Nataraja sculptures implies they were inspired by real dance,” Padigar said.

Saavukoothu, too?

“Earlier, fallen soldiers were accorded grand farewells by the king’s military, like today’s 21-gun salute. That practice got more democratised and became Saavukoothu,” Ragothaman, the Chennai priest, said explaining the more historical roots of the practice. Sivaramamurti also wrote that Shiva-obsessed Chalukyan soldiers often insisted on the Nataraja being engraved on their tombstones “in the confidence that they would be victors like their lord.”

For now, though, this connection is only tentative.

Soon, however, another profound transformation happened to Nataraja in the south.

Chidambaram, the centre of “cosmic consciousness”

Chidambaram is a dusty small town along the Tamil Nadu coast—yet some 20 million people visit or make a pilgrimage every year to its tragically ill-maintained Shiva temple. Even overwhelmed by dust and cobwebs, the architectural gem carries centuries of aesthetic, philosophic, and spiritual history etched on its walls. Unlike most other Shiva temples in southern India, where he is worshipped in his linga form in the main sanctum, here Nataraja, too, is worshipped. Bronze is the medium here, believed to have been installed under the Chola dynasty, which revived as the Pallavas weakened due to incessant wars with the Chalukyas.

Chidambaram derives its name from a combination of chit or consciousness (in Sanskrit) and ambaram or cosmos. “In that sense, this spot of Nataraja in this temple may be considered the centre of cosmic consciousness,” says Devi Bala Dikshitar, one of the many priests officiating there.

The shift to the copper alloy helped perfect the image. “It seems that only with an appreciation of the greater tensile strength of metal, compared to wood, were the limbs, locks, and sash flared out more... towards a circular shape,” says Sharada Srinivasan, an archeologist who studies ancient metals at the National Institute of Advanced Studies, a multidisciplinary centre located at Bengaluru’s Indian Institute of Science campus.

The five-foot-something Nataraja idol here is awe-inspiring even in the cold darkness of the sanctum. One can only imagine the tremendous impact it must have had on devotees the day it was first brought out in the open, to be taken in procession around the temple, likely in 1054—a year that marked an awe-inspiring, real cosmic performance in the skies.

“It may have been linked to the observation of the Crab supernova explosion in 1054 which was also recorded by Chinese astronomers as being visible from July 4 for several days,” says Srinivasan.

Other astronomical connections, too, emerge. For instance, a major festival is held in Chidambaram at the time of the winter solstice in December. During that time, the Orion constellation is seen in its zenith above the temple.

Whatever the reason, it is clear that some time in the mid-11th century the Chidambaram temple began celebrating the festival during which this particular Nataraja statue was taken out in procession.

In his book Coromondel, historian Allen writes that the awestruck devotees would not have missed the link between this radical “cosmic-encompassing god and his royal representative on earth,” the Chola emperor.

Some nine centuries later, Shiva would emerge yet further from the temple, finding new devotees in the world.

Nataraja’s global journey turns to the west

In the early part of the 20th century, Sri Lanka-born art historian and scholar Ananda Coomaraswamy made inroads into the western mind with his philosophical, spiritual, and cosmic interpretations of the Nataraja. British enthusiasts and historians had till then been dismissive about Indian art unless it was influenced by Greek aesthetics, Allen writes. Coomaraswamy’s seminal 1912 essay, The Dance of Siva, later published in his influential collection of essays on Indian art and culture, might be deemed the launchpad of the Nataraja’s global journey.

Citing the many versions of Shiva’s dance, Coomaraswamy said the root idea behind all of them was the “manifestation of primal rhythmic energy.” He wrote:

In the night of Brahma, Nature is inert, and cannot dance till Shiva wills it. He rises from His rapture, and dancing sends through inert matter pulsing waves of awakening sound, and lo! matter also dances appearing as a glory round about Him. Dancing He sustains its manifold phenomena. In the fullness of time, still dancing, he destroys all forms and names by fire and gives now rest. This is poetry; but none the less science.

According to archaeologist Srinivasan, Coomaraswamy’s aesthetic sensibilities and his background as a scientist—he had studied geology and botany—both come through in his essay on Nataraja. His writings “seem to be echoed in TS Eliot’s famous poetic lines ‘At the still point of the turning world…there the dance is…’ Celebrated French sculptor August Rodin (1913) in his essay ‘La Danse de Siva’ illustrated it with the same Nataraja bronze from the Government Museum, Chennai, as did Coomaraswamy,” she wrote in a 2016 paper.

Born in what was then Ceylon to a Tamil father and an English mother, Coomaraswamy was well placed to interpret Nataraja for a western audience—he served as curator at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts from 1917 for three decades until his death, and was one of the first to build a large collection of Indian artworks in the US.

“Coomaraswamy made Indic art accessible and compelling to many Americans and Europeans in his prolific writings. His essay on the Nataraja may have been especially appealing because of the admirable character and profound ideas it ascribed to that deity, as well as the confidence with which it fixed the meaning of this elaborate sculptural form,” notes Padma Kaimal, a professor of art history at Colgate University, New York, who nonetheless challenges his seminal reading in her own work, citing the fragmentary nature of evidence surviving from medieval southern India among other reasons.

A philosopher-theologian as well, Coomaraswamy corresponded with the likes of science-fiction writer Aldous Huxley, and may perhaps have even inspired some of his work, which included studies of mysticism.

Huxley himself, as the introductory quote suggests, was enamoured of Nataraja. “The great world of all-embracing material world with its flames, within this Shiva dances… He is everywhere in the universe. This is his dance, the manifestation of the world called his Leela, his play. His sense of reign upon the just and the unjust and he is not beyond good and evil, of course, it is all an immense manifestation of play,” he says in a 1961 interview.

Summer of ’69: Life, the universe, and Shiva

Fifty years ago, the full swing of the counter-culture movement gave an entire generation in the West a new high, helped by a heady concoction of eastern mysticism and psychedelic drugs. Many experienced epiphanous moments; for some, even life-changing ones. Fritjof Capra, the Austrian-born American physicist, 80 years old now, was among them.

In an email to Quartz, he said:

In the Summer of 1969…one late afternoon, I was sitting by the ocean (in California)…when I suddenly became aware of my whole environment as being engaged in a gigantic cosmic dance. As a physicist, I knew that the sand, rocks, water, and air around me were made of vibrating molecules and atoms, and that these consisted of particles that interacted with one another by creating and destroying other particles…but until that moment I had only experienced it through diagrams and mathematical theories…I “saw” the atoms of the elements and those of my body participating in this cosmic dance of energy. I felt its rhythm and I “heard” its sound; and at that moment I knew that this was the Dance of Shiva.

More such experiences followed. Six years later, he summarised his findings in The Tao of Physics, published first in 1975. The book was received enthusiastically in the US and Europe and, at least for some, revolutionised both their spiritual and scientific planes.

A lot has changed in the field of particle physics since Capra’s “moment.” However, he says, nothing has “invalidated the two grand themes of modern physics—the fundamental unity… and the intrinsically dynamic nature of its natural phenomena.” That dynamic nature of physical reality is embodied in the myth of the dancing Shiva, he adds.

Before Albert Einstein propounded his theory of relativity in the early 20th century, it was assumed that matter could ultimately be broken down into indivisible indestructible parts. But when individual subatomic particles were smashed against each other in high-energy experiments, they didn’t scatter into smaller bits. Instead, they merely re-arranged themselves to form new particles using kinetic energy or the energy of motion: subatomic dynamism.

“At the subatomic level, all material particles interact with one another by emitting and reabsorbing (i.e., creating and destroying) other particles. Modern physics shows us that every subatomic particle not only performs an energy dance, but also is an energy dance; a pulsating process of creation and destruction. For the modern physicist, then, Shiva’s dance is the dance of subatomic matter,” Capra said in his email.

This insight of Capra’s is what catapulted Nataraja into the status of a global icon in the 1970s. But he credits his ability to make these connections to his familiarity with works on mysticism by eastern and western scholars—like Coomaraswamy’s Shiva essay. “I immediately saw parallels to some ideas in quantum physics,” Capra says.

Astronomer Carl Sagan was another one fascinated by these synchronicities, writing in his book Cosmos, which became a 13-part miniseries with one episode shot in India, that he liked to imagine the Nataraja was “a kind of premonition of modern astronomical ideas.”

This idea of the eternal universal dancer has so deeply caught on among physicists and cosmologists that in 1993, an abstract sculpture called Cosmic Dancer, was launched to the Russian Mir space station. Asked about how his artwork, its designer Arthur Woods said:

…the (Nataraja) appears very angular yet aesthetic with the four arms outstretched and the raised front leg. Thus my sculpture, which is also very angular could be viewed as a symbolic abstraction of this figure as it dances in the cosmic weightlessness of space…its form is always in a transient state of change…This and the fact that it is free of terrestrial gravity, imparts a supranatural quality normally reserved for gods. Thus this qualitative relationship to the god Shiva can be made.

In 2004, the government of India gifted the European Organization for Nuclear Research, or CERN, a 2-metre tall Nataraja statue which now stands at the entrance of the facility in Switzerland where the world’s most powerful particle accelerator, or the Hadron Collider, became operational in 2008. It has prompted enough curiosity that the CERN website addresses its presence:

This deity was chosen by the Indian government because of a metaphor that was drawn between the cosmic dance of the Nataraj and the modern study of the “cosmic dance” of subatomic particles.

The last dance

A few days after I first met Rajkumar, I got a call from him, inviting me to accompany him. The group had been called to a Chennai neighbourhood where a young woman had tragically lost her battle to leukaemia. It was to send her off.

After the exhausting session, during which around 10 adults and a few children danced for a few hours, we settled down for a cup of tea. “We have at least one body to accompany a day. Sometimes it is the elderly, sometimes little ones. All leaving behind a trail of wails and tears,” Rajkumar said.

Is he too inured by now? “We have seen too many...we realise this is an inevitable part of life,” he said, eyes glazing over. As we bid farewell in the afternoon heat, I had one last question to garnish my piece with: By any chance, was there anyone named Shiva in Rajkumar’s team?

Amused, he replied:

My Tamil name is Tondaimaan. Tondaimaan is Shiva.

We welcome your comments at [email protected].