Here’s an amazing app for learning music

All musical notation is a kind of compression, which is to say a compromise between ease of transmission and depth of reception.

All musical notation is a kind of compression, which is to say a compromise between ease of transmission and depth of reception.

The notes on a score tell you a lot about a song, but not everything. The same goes for guitar tabs, which tell you where to put your fingers, not what the notes are.

So, if you want to learn a song, it’s best to hear someone playing it decompressed, while using the notation as an aide-mémoire.

This isn’t an easy thing to do, especially in the repetitive way that’s necessary to learn a song.

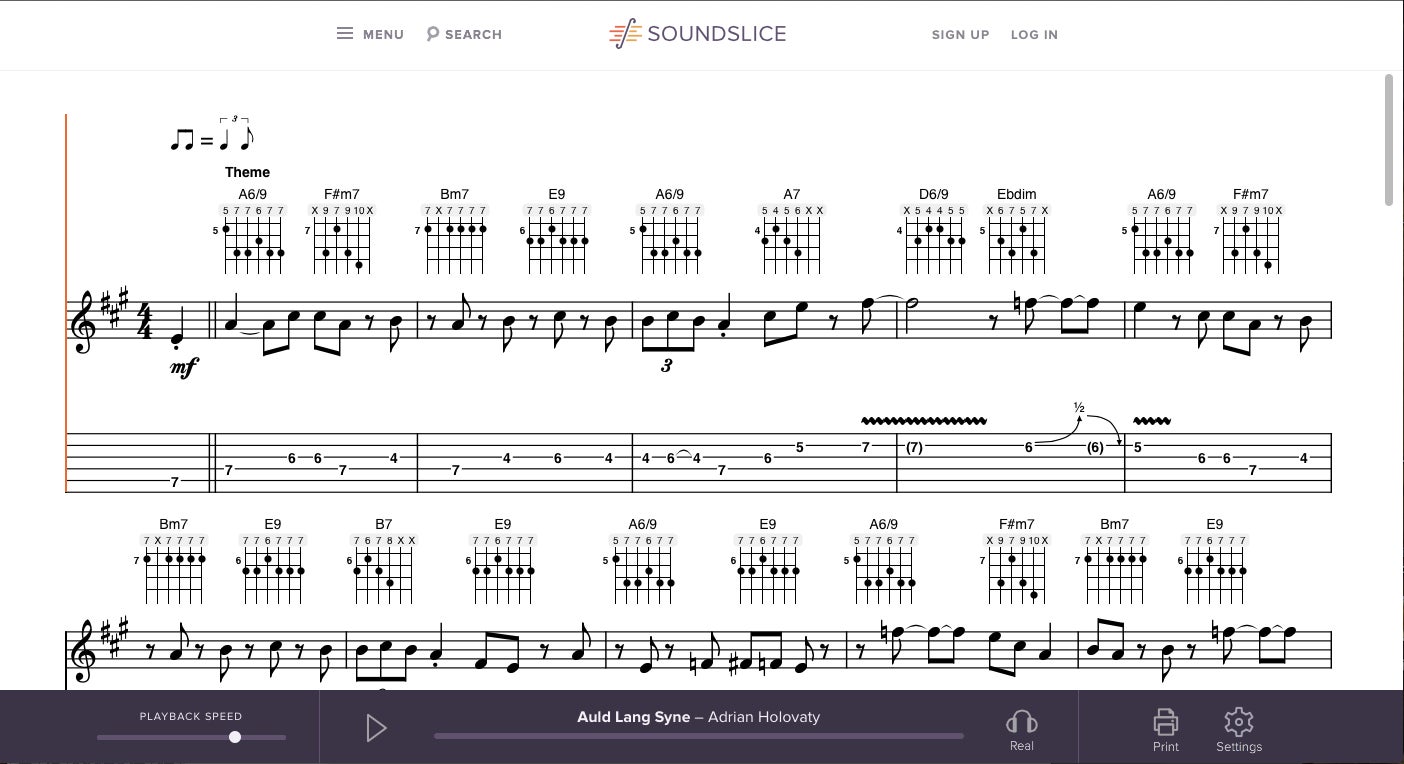

Or it wasn’t until Adrian Holovaty and PJ Macklin created Soundslice, a beautiful HTML5 app that syncs professional studio recordings with sheet music and guitar tablature. Soundslice debuted in late 2012, but they released a new version of the software for sheet music on Mar. 17, and it’s wonderful. You can check out the functions in the video below:

But really, go play around with the app. There’s a nice version of Auld Lang Syne. Do it on any device. Phone, tablet, laptop. Soundslice works beautifully. Not just functionally, but smoothly, responsively. Writer, developer, and all-around web guy Paul Ford said that “it sings,” and that’s a great way of putting it.

And it sings everywhere, or as Holovaty put it to me and Ford on Twitter, “HTML5 FTW! Screw native apps and their walled gardens.” The problem with that has always been speed. Generally speaking, native apps respond to touch better; you caress, they respond. HTML5 apps tend to be laggier and just don’t have that polished, quick feel. Soundslice shows it can be done, though.

The service does have limitations, of course: Only songs that they’ve commissioned or had transcribed by their community are available to learn.

And I’m sure people might question the business model, too, or wonder whether it’s the best way to maximize the profits from this kind of technology. But that’s like asking John McPhee why he’s not Malcolm Gladwell.