US fishermen throw back 20% of their catch—often after the fish are already injured or dead

Each year, the 41 Alaskan trawlers licensed to sift the seas for flatfish—such as flounder and sole—haul back around $6 million worth of fish. Boat space is limited, so fishermen save it for only the priciest fish. That means the less-valuable fish go back over the side, along with the hundreds of other sea creatures that these fishermen can’t sell back on land, because they’re funny-tasting, too small, simply wrong kind of fish, or even an endangered species.

Each year, the 41 Alaskan trawlers licensed to sift the seas for flatfish—such as flounder and sole—haul back around $6 million worth of fish. Boat space is limited, so fishermen save it for only the priciest fish. That means the less-valuable fish go back over the side, along with the hundreds of other sea creatures that these fishermen can’t sell back on land, because they’re funny-tasting, too small, simply wrong kind of fish, or even an endangered species.

By the time they’re tossed back, many of these animals are already dead (pdf, p.7). Just how destructive is this practice?

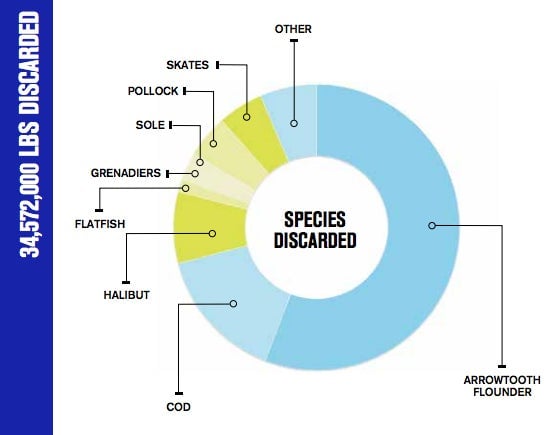

A new report by Oceana (pdf), an NGO concerned with ocean wildlife conservation, estimates that these Alaskan flatfish trawlers are throwing back around $17.7 million worth of fish a year. That’s right: nearly three times the value of what those fishermen actually sell.

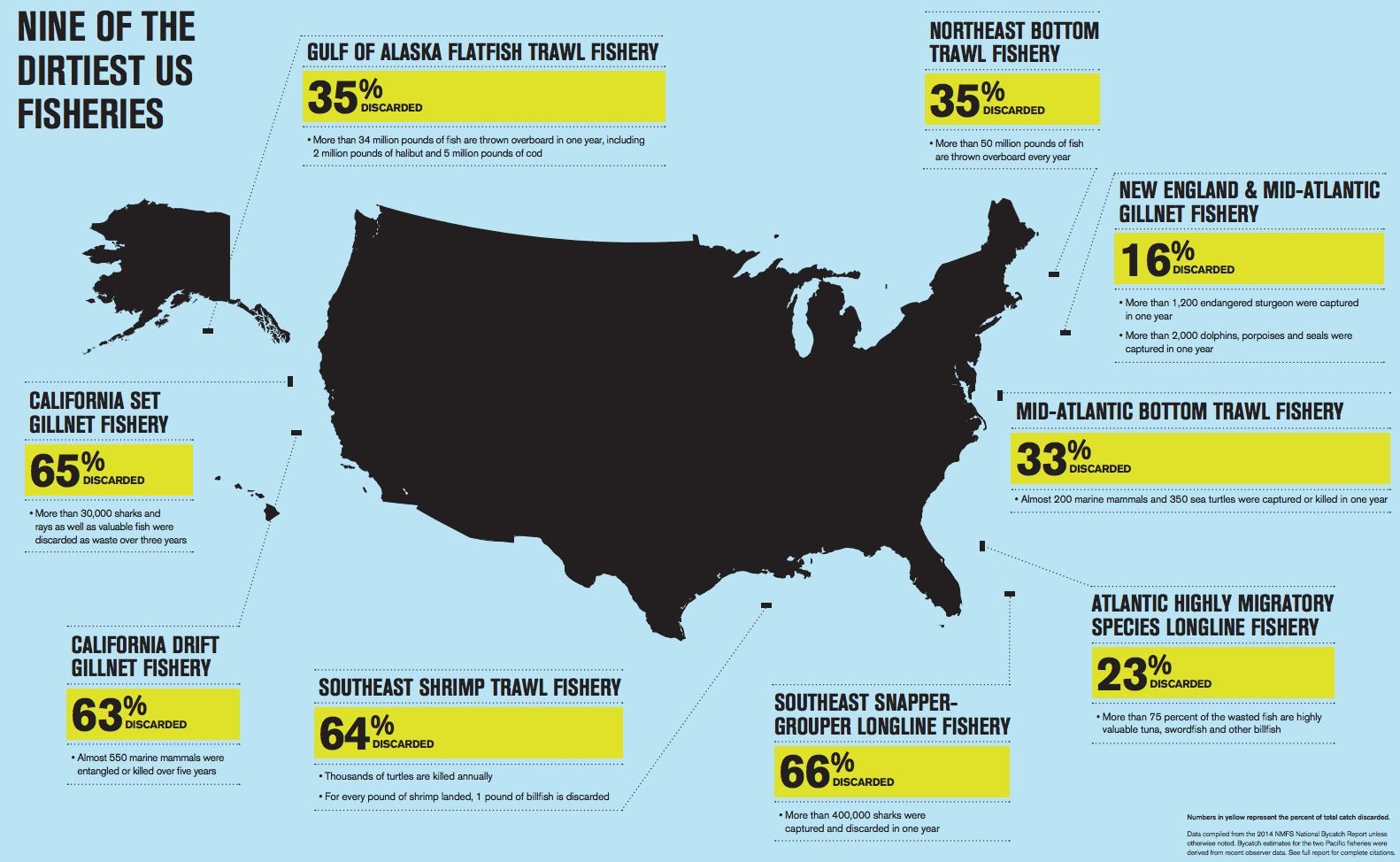

Alaska, alas, is not an outlier. Oceana calculates that, all told, 17-22% of what all US fisheries haul up is discarded as bycatch, which is what the industry calls the fish that are thrown back, dead or alive. That adds up to a minimum of 2 billion pounds chucked back each year—or about 4.5 ounces for every pound of seafood the average American eats.

Here are some of the startling figures from Oceana’s report:

- The $90 million Northeast Bottom Trawl fishery discards 35% of its catch. 50 million pounds of fish are thrown back each year.

- The $13.8-million Southeast Snapper-Grouper Longline fishery discards 66% of its catch. More than 400,000 sharks were thrown back in a single year.

- The $450,000 California Set Gillnet fishery discards 65% of its catch. The fishery caught 94 baby great white sharks in a five-year period. Around half of them were dead on arrival.

- The $314-million Southeast Shrimp Trawl Fishery discards 64% of its catch. Thousands of sea turtles die trapped in nets each year.

Why is this happening? To keep up with surging global seafood consumption, the fishing business long ago industrialized, harnessing increasingly powerful engines to drag bigger nets farther, faster. Over the past six or so decades, this steady industrialization has collapsed or threatened the populations of America’s favorite fish species, including Atlantic cod and Pacific halibut.

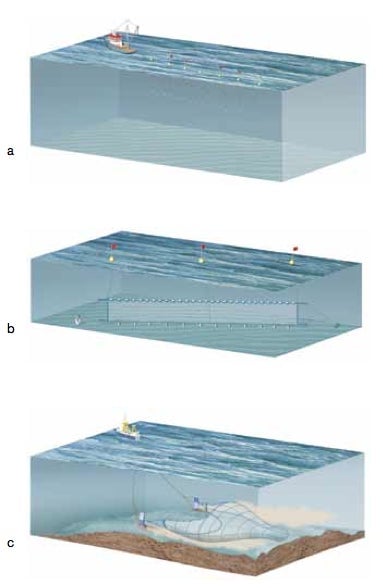

The depletion of those standbys has encouraged still more industrialization. To catch rarer species, fishermen must travel farther, and cast those bigger nets many more times to land the same number they once did. Boats now rake the sea with trawl nets as wide as football fields, says Amanda Keledjian, one of the report’s authors. And longlines—ropes with thousands of baited hooks attached—can trail 50 miles behind boats.

It’s probably no coincidence that seven-eighths of the species targeted by the Southeast Snapper-Grouper fishery—which has the highest discard rate—are currently overfished. The rarer the target species, the more bycatch dies at sea.

This not only further endangers vulnerable species; it also has dire economic consequences. One fishery’s bycatch is oftentimes another fishery’s prize catch.

Take for example bluefin tuna, whose stocks are in such precipitous decline that Japan—the fancy fish capital of the world—just announced that it’s slashing its catch limit on juveniles by half. The species’ rarity means it’s pricey; Japan paid around $10 per pound on US Atlantic bluefin tuna last year, according to the National Marine Fisheries Service data.

Protecting juveniles is vital to preventing their numbers from shrinking further, which is why regulations in Japan, the US and other places prevent their capture. But those laws do little if juveniles don’t survive long enough to reproduce. The vessels in the $52-million Atlantic Highly Migratory Species Longline fishery threw back twice as many bluefin tunas as they were allowed to keep (presumably due to rules banning capture of juveniles), says Oceana—disquieting given generally high mortality rates (pdf) for longline-caught bluefin tuna.

Pacific halibut offer an even more vivid example. The stocks of these valuable fish, which can grow up to eight feet (2.4 meters) and spoil slowly, have plunged in the last decade—even in the Gulf of Alaska, the nursery ground for the species. The authorities forbid Alaskan flatfish trawlers from keeping the halibut they bring aboard as bycatch for fear that allowing them to sell the species would lead to their targeting it. The problem is, an estimated 40-70% halibut die in the process of being snared as bycatch and discarded.

That worsens the halibut shortage and robs Alaskan halibut fishermen of at least around $13.5 million annually, according to Oceana estimates. The damage it does is potentially far greater, though; as Alaskan halibut fishermen point out, the dwindling sizes of the halibut population because that trawlers reporting the same weight in bycatch each year are actually killing more fish.

This hidden overfishing perverts ecosystems. For example, imploding Atlantic shark populations allowed an explosion of cownose rays, which then gobbled up the region’s valuable bivalve populations, making clam chowder pricier. Overfishing ultimately risks causing what scientists call “ecosystem flips“—big population shifts that alter the ecosystem permanently.

Unlike the nine US fisheries that Oceana highlights, many fisheries are taking steps to reduce bycatch and diminish bycatch mortality.

This largely comes down to initiative, though. Federal law devolves fishery management—including conservation—to eight regional agencies. So economic priorities, reporting protocols and enforcement vary widely, even as the species they aim to manage span the various regions. Oceana reports that fewer than five percent of US fisheries document bycatch in line with federal standards, making it hard to gauge the urgency of adopting more sustainable practices in a single region, let alone across several.

It also means the death-by-bycatch problem is worse than many realize—something that finicky American consumers, and not just regulators, would do well to note. You can understand why fishermen go after premium species; those are the ones that Americans deign to eat. Decades of serving these narrow tastes forced fishermen to dig through a haystack for a tiny diminishing number of needles. If we ate a little more of that haystack, it would make life a lot easier for fishermen and fish alike.