The biggest semiconductor deal in history should have been even bigger

Nvidia’s planned planned acquisition of Arm Holdings is the biggest semiconductor deal in history. Yet, one of the surprises about Arm’s $40 billion valuation is how small it is.

Nvidia’s planned planned acquisition of Arm Holdings is the biggest semiconductor deal in history. Yet, one of the surprises about Arm’s $40 billion valuation is how small it is.

Japanese conglomerate SoftBank is offloading Arm, the British chip maker it bought four years ago, for $31.4 billion (also a record), which amounts to a return of about 27%. That lags well behind the 55% gain for the S&P 500 Index of large US companies during that span, not to mention the skyrocketing share price for California-based Nvidia, which has a market capitalization of more than $300 billion.

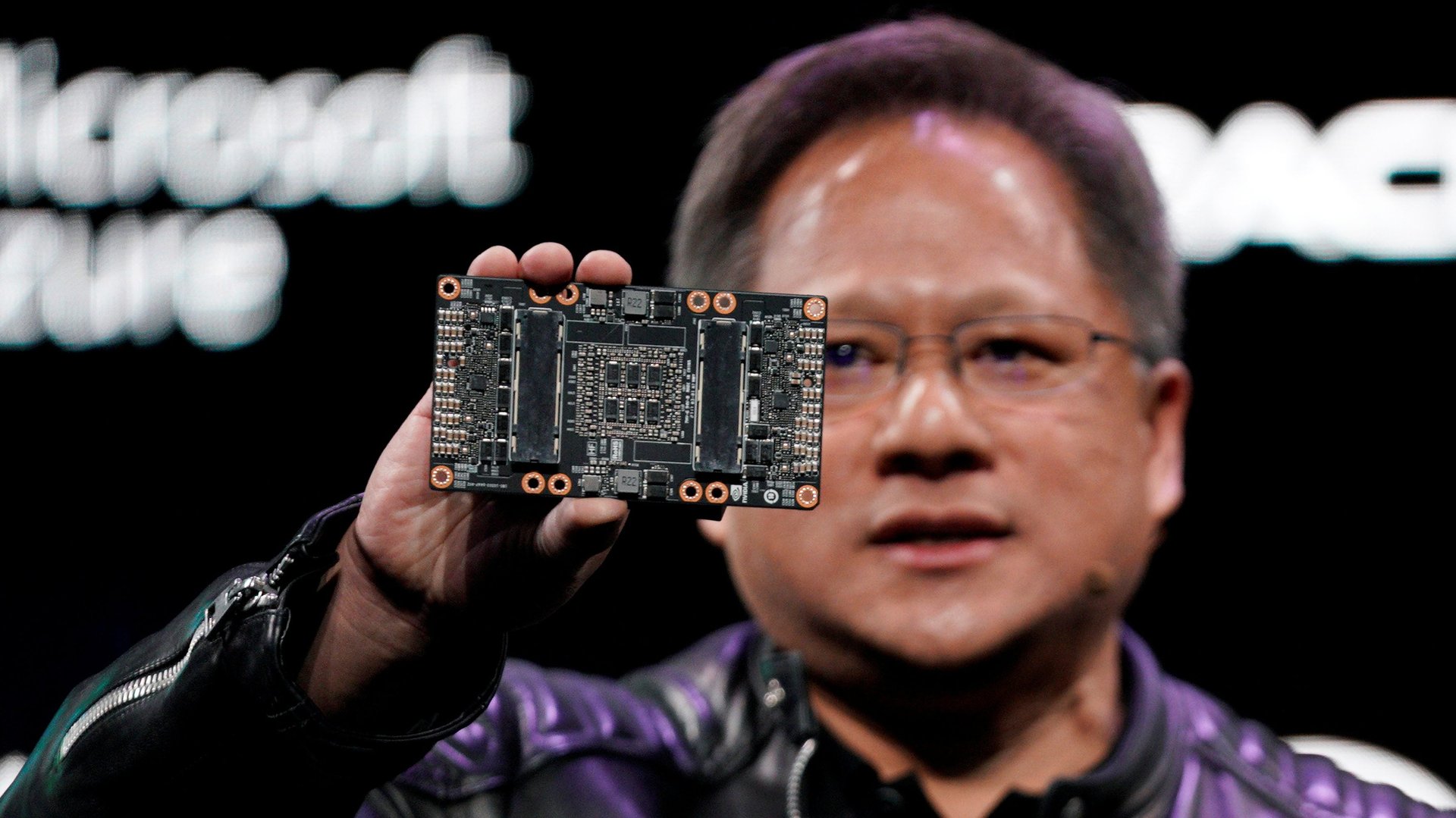

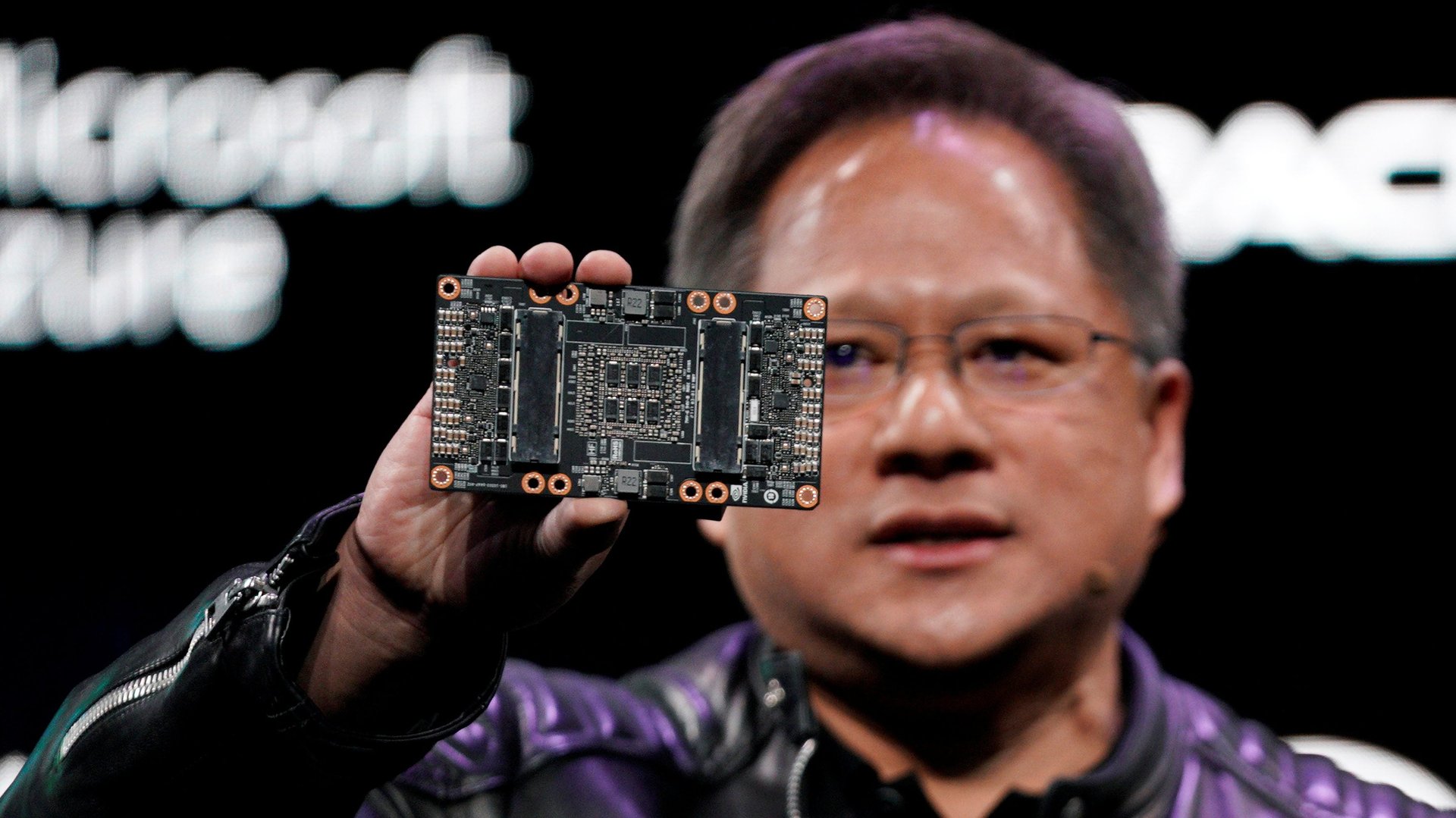

Arm’s relatively droopy valuation suggests it hasn’t been optimized under SoftBank’s ownership. Some analysts and investors think the Nvidia deal, while controversial, will ultimately help Arm live up to its potential by providing the company with more resources. Nvidia makes GPUs—the chips that power everything from computer graphics and gaming to artificial intelligence in data centers—while Arm designs the blueprints for processors used for a wide array of purposes, from energy-sipping smartphones to supercomputers.

“If Arm would have stayed on the stock market it would have been, maybe, the most valuable European technology company,” said Per Roman, managing partner and co-founder of investment firm GP Bullhound, which owns Nvidia shares.

Arm’s sale to an American company has also revived a long running question—why doesn’t Europe have the kind of tech giants that roam in the US and China? A lot of it probably comes down to money. Scaling quickly can require the kind of aggressive mega investment that’s less available outside of Silicon Valley. Another likely factor is the US’s large market—it has one currency and one language, and companies can (usually) expand from one state to another relatively smoothly.

Whatever the reasons, Europe’s technology jewels have often ended up in another region’s crown. Google bought DeepMind, one of Britain’s leading AI startups, for around $500 million in 2014. UK prime minister Boris Johnson and Dominic Cummings, his top advisor, reportedly dream of creating a British titan that’s in the same league as Google, and they’ve debated using state aid to help them get there.

“We have largely been willing to sell our companies to US consolidators that are maybe more bold, more aggressive, and willing to pay higher valuation,” Roman said. For investors to really open their wallets in Europe, they need evidence that the region’s entrepreneurs can perform. “You have to understand that the venture and growth capital ecosystem in Europe is really only 20 years old.”

Roman thinks that’s changing, and he points to the rise of companies like Adyen, the $53 billion payment company in Amsterdam, and Stockholm-based Spotify’s $44 billion market capitalization. “More and more European companies are becoming leaders and giants on the US stock market,” he said in a phone call. “In the best of worlds, Arm would have stayed an independent business. Since that disappeared, it’s a lot better to be owned by Nvidia. It’s the premiere company in that segment of semiconductors.”

The takeover is controversial for other reasons as well. Arm co-founders Hermann Hauser and Tudor Brown argue that, once the chip designer is under an American company’s control, Washington could try to use its technology sales as a weapon against China. “The decision on whether they will be allowed to export it will be made in the White House and not in Downing Street,” Hauser said in an interview with the BBC. The pair said they are also concerned that Arm could be exploited to make Nvidia’s processors more advanced, to the detriment of the UK company’s other customers.

Executives at the companies have played down those criticisms, arguing that most of Arm’s products are designed in the UK, putting them outside the reach of Washington’s exports controls. Nvidia says it won’t meddle with Arm’s business model, although some analysts think the company could be tempted to do so if it starts to seem lucrative enough.

One of the biggest worries is what happens in Cambridge, where Arm is based and the locus of many top-tier computer engineering and AI jobs. Back in 2016, SoftBank committed to keep those roles in the UK. Now, Jensen Huang, founder and CEO of Nvidia, said Arm’s headquarters will stay there, and that his company will build a state-of-the-art AI supercomputer in Cambridge using Arm’s CPUs.

Brendan Burke, an analyst at PitchBook, thinks the super computer plan is a sign that Nvidia is going to lean into Arm’s capabilities rather than looking for cost cuts. He argues that the companies are working on much different types of processors and that Nvidia will need the British firm’s IP and research and development capabilities, and, particularly, its elite team of computer scientists.

“I genuinely believe they will keep the Arm team and R&D development and operations in Cambridge,” Roman said. “There’s real competence in this area, and that’s not something you can just export willy-nilly to Silicon Valley.”