Presidential debates are a showcase event of the US election cycle, commanding live coverage around the world and much political analysis, but they have little impact on election outcomes. Even if voters say debate performances will influence their choices, historic evidence suggests that there isn’t a link between good debate performances (or even debate “victories”) and election results.

In this year’s polarized election climate, it’s likely the three debates between president Donald Trump and former vice president Joe Biden—the first of which is tonight at 9pm US eastern time—will matter less than ever. The percentage of Americans who say they are still undecided is much smaller than in past years.

The question of whether debates help advance the democratic conversation or are just mere performance is a valid one. After all, they are a relatively new development of American democracy.

Although the origin of the direct political debate is often pinned to a series of epic debates between Abraham Lincoln and Stephen A. Douglas, who in 1858 were running against one another for an Illinois senate seat, the debate between presidential candidates occurred much later. The first presidential debate was held in 1956—between two women.

When Democratic candidate Adlai Stevenson challenged president Dwight Eisenhower to a televised debate, the confrontation wasn’t between the two candidates but two surrogates, former first lady Eleanor Roosevelt, who like her late husband Franklin Roosevelt was a Democrat, and senator Margaret Chase Smith, a Republican from Maine. The two met on CBS’s Face the Nation (the first female guests in the show’s history) two days before the election, to discuss foreign policy. The debate got heated: By the end of it, Roosevelt was upset and refused to shake hands with Smith.

This TV debate wasn’t what Fred Khan—the man credited with adding debates to modern democracy—had envisioned. In 1956, Khan, then a college student, started a campaign to see the two presidential candidates face off on campus at the University of Maryland. His idea caught much student support and a letter advocating for the debate reached the Eleanor Roosevelt—though it’s unclear whether it is connected with her decision to debate Smith.

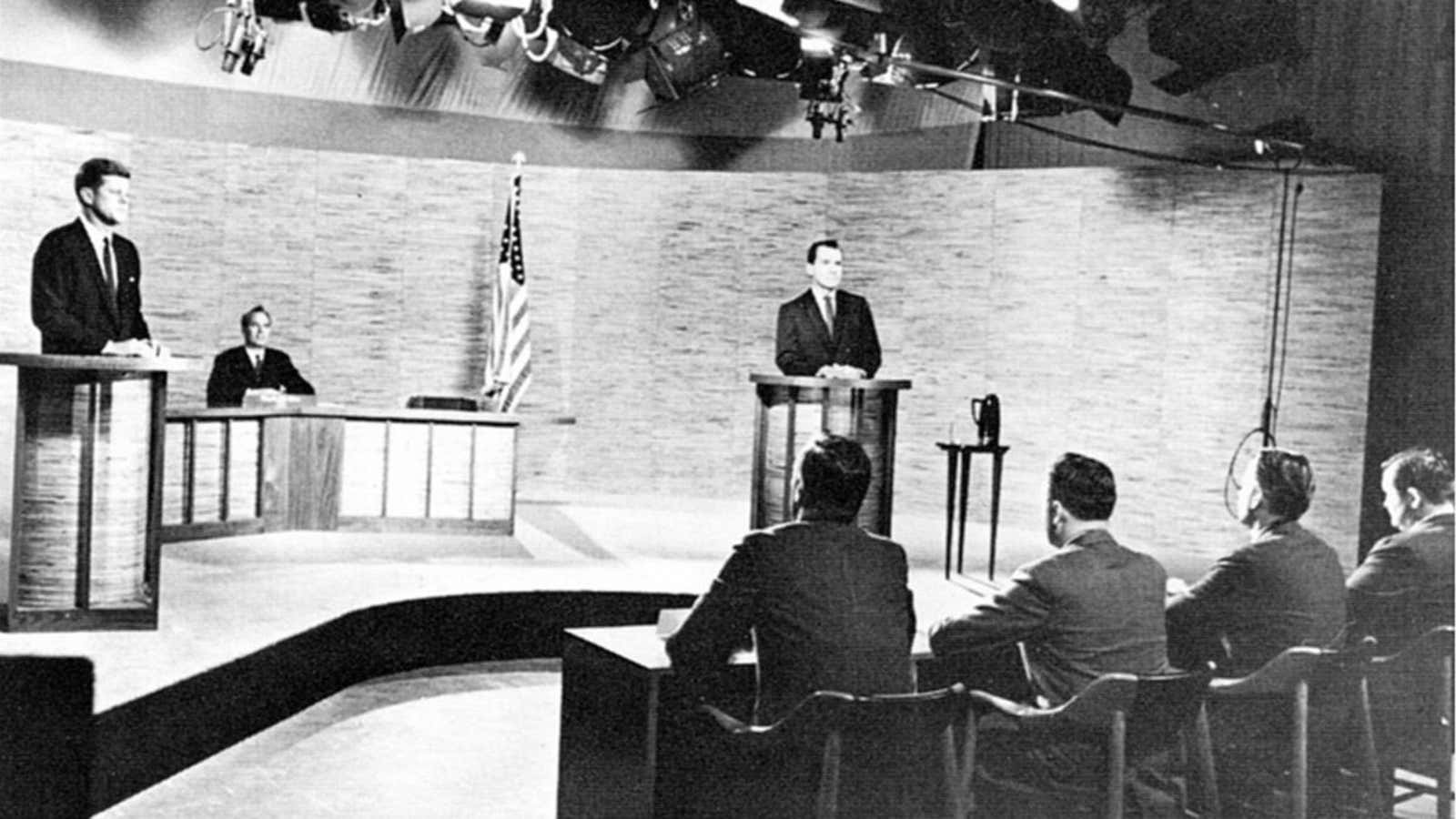

Khan’s advocacy paid off the following election, when Richard Nixon and John F. Kennedy debated in person four times on live TV.

Much like today, TV networks were set to be the sure winners of the debates—which is why they sponsored them.

The 1960 debates offer insight into how arbitrary the evaluation of a debate performance can be. At the time, those who watched the debate on TV thought Kennedy, who had a better TV presence, dominated it, while those who listened to it on the radio felt that Nixon had a stronger performance.

Those first debates were also the official acknowledgement that, while many other candidates were running for election—some states had as many as 20 presidential candidates on the ballot in 1960—there were only two viable ones. In order to hold the televised debate, a rule that demanded equal time be offered to all candidates had to be suspended, since only the Democratic and Republican candidates were going to appear in the debates.

Supporters of live debates highlight how they helped spur voter interest—turnout climbed from 60.4% in 1956 to 64.5% in 1960—but it’s hard to tell whether it was the broadcast, or the personalities, that engaged voters. After all, the turnout increased even more in the 1964 elections, held without debates—and later decreased despite the many subsequent live confrontations.

After 1960, there wasn’t a debate till 1976, since Lyndon B. Johnson and Nixon both refused debating their opponents. During those years, arguments in favor of live debates continued, with the support of TV networks.

Live debates were then organized for every election after Jimmy Carter and Gerald Ford’s and by 1987 they had become such an important part of the democratic process that the Commission on Presidential Debates (CPD) was created with Democratic and Republican support to establish the rules of the debate.

Worldwide, presidential debates are now understood to be a fundamental fixture of American democracy, and the CPD offers support to countries interested in setting them up. So far, according to the CPD, it has helped set up debates in Bosnia, Burundi, Colombia, Côte d’Ivoire, Ghana, Haiti, Jamaica, Lebanon, Niger, Nigeria, Peru, Romania, Trinidad and Tobago, Uganda, and the Ukraine.