One in five Irish mortgages is behind on payments

The bond markets are loving Irish government debt. Sky-high Irish unemployment is slowly trending lower. And Irish consumers are feeling better than they have since the boomiest moments of the Celtic Tiger economy.

The bond markets are loving Irish government debt. Sky-high Irish unemployment is slowly trending lower. And Irish consumers are feeling better than they have since the boomiest moments of the Celtic Tiger economy.

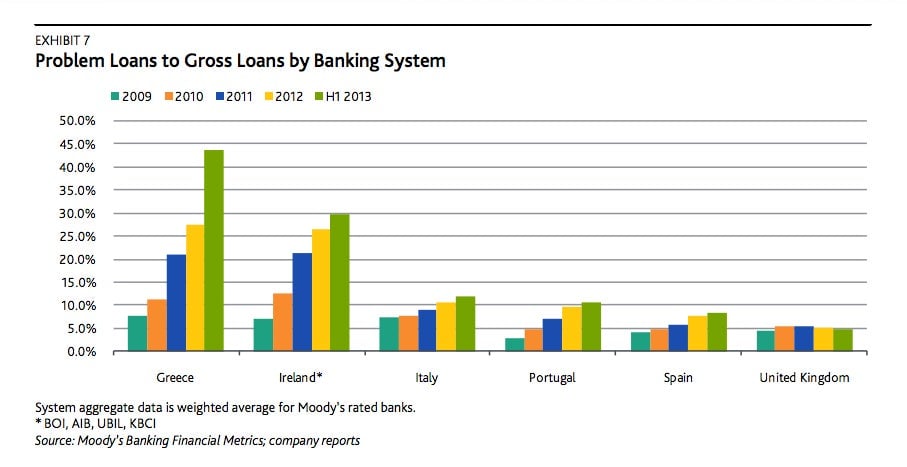

But the root cause of the country’s economic woes—its terrible banking system—remains an unsolved problem. You’ll remember that when Ireland’s ridiculously over-leveraged banking system collapsed in 2010, the government—which tried to bail it out—was pulled under too. (The Irish government was forced to seek a bailout from the ECB, the European Union and the IMF.)

Ireland’s banks are still in shambles, according to an update from credit rating firm Moody’s.

Why? It’s the assets, stupid. Moody’s analysts write:

Irish banks’ largest loan book exposure is to domestic residential mortgages. Our main source of concern is mortgages that are more than two years in arrears. The balance of such mortgages has jumped to €10.8 billion at the end of 2013, accounting for 8% of total mortgage loans, from €7.3 billion at the end of 2012, accounting for 5% of total mortgage loans. At end-Q4 2013, about 20% of Irish mortgage balances were more than three months in arrears.

Those high levels of arrears will likely translate into substantial losses for the banks. And those losses will eat into the cushion of capital—basically the equity and cash—that keep banks solvent.

The upshot? Upcoming ECB bank stress tests—results are due in October—will likely reveal some holes in Ireland bank balance sheets. Somebody will need to fill them. Private investors have shown some inclination to invest in Irish banks, but they’re not overly eager. Losses imposed on creditors could plug some of the holes. And by the way, any equity the banks raise will dilute the current shareholders. Since some banks (such as Allied Irish) remain majority-owned by the Irish government, that means the taxpayers will foot part of the bill, again.