How a Texas county is handling record voting turnout during a pandemic

With a population of 1.3 million, Travis County, which includes the city of Austin, is Texas’s fifth largest.

With a population of 1.3 million, Travis County, which includes the city of Austin, is Texas’s fifth largest.

Ahead of the presidential election, its registrar achieved quite a feat, registering 97% of the eligible population.

Early voting began on Oct. 13, and over 35,000 voters cast ballots on the first two days. Election officials expect a record turnout.

But how does a county’s election office handle such large turnout in the middle of a pandemic, one that requires everyone to wear personal protection equipment (PPE) and remain six feet away from the closest person? With an expanded team, and some innovation.

“I’ve had to double the size of our call center and move everybody into other spaces in the buildings in order to keep that crew socially distanced,” says Dana Debeauvoir, Travis County’s clerk. “I’ve had to triple the normal amount of people I would have for ballot-by-mail processing.” The call center, she says, now has 50 employees, while another 60 are receiving mail-in ballots. Another 40 workers comprise the ballot board—a team dedicated to certifying mail-in ballots, checking signatures and addresses, and ensuring no information is missing.

In any other election, Debeauvoir says she’d hire only 20 for the job, but this time they are expecting about 100,000 mail-in ballots to reach the election office. So, she expanded the group to 40, adding new hires to a core group of seasoned election workers she had relied upon in previous years. She needs more poll workers, too—3,000, compared to the 2,500 of previous elections— and she’s still hiring.

In order to encourage voting despite the added difficulties, the county has employed some innovations, too. One is drive-through voting, for absentee ballots. “It’s just like what it sounds like,” says Debeauvoir. “A voter drives in with their ballot…they go through a process of showing voter identification, signing a poll roster, then seeing their ballot put in the ballot box. And then they drive away.”

So far, she says, the team has been able to keep the drive-through voting time at two minutes per voter—with about 15 minutes wait beforehand.

The capacity of the drive-through drop-off location—which can also be accessed on foot—was expanded when Texas governor Greg Abbott ordered that drop-off locations for absentee votes be limited for one per county, says Debeauvoir. Travis County had set up four drop-boxes.

“In the middle of the first day the governor abruptly ordered us to close those locations—with voters in line,” says Debeauvoir. As the only location that could be kept open was the election office, the drop-off point was moved to the building’s parking lot, allowing for 16 receiving gates, more than the 11 the county had with the original four locations before the order.

Lines at the early voter polls—and on election day—may be longer than for the drop off. But there’s a map for that. The map shows the name of every open polling place, and next to it a traffic light—green for wait of 20 minutes or less; yellow for waits up to 50 minutes; red for waits of 51 minutes and more. Voters can choose the polling place based on that information.

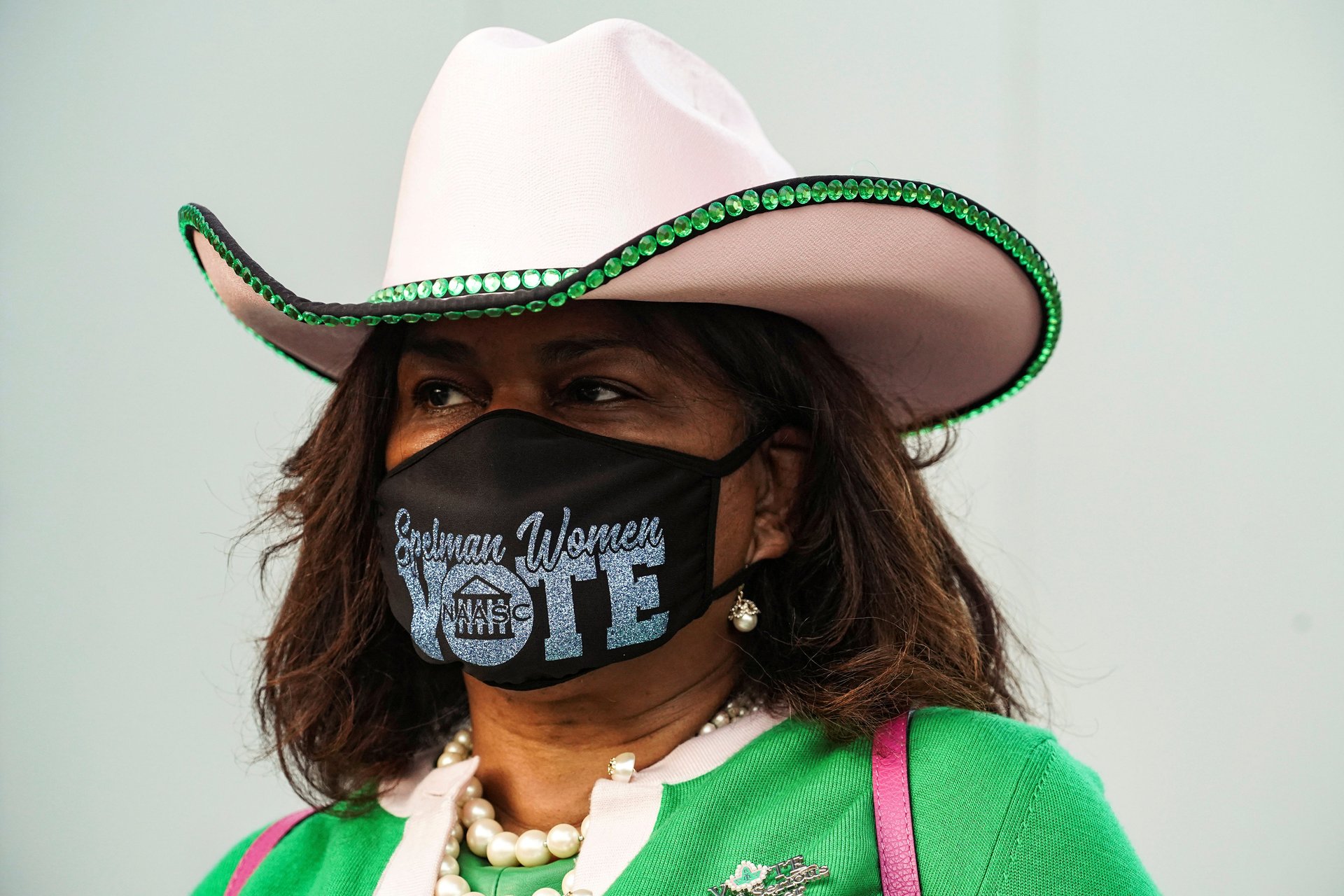

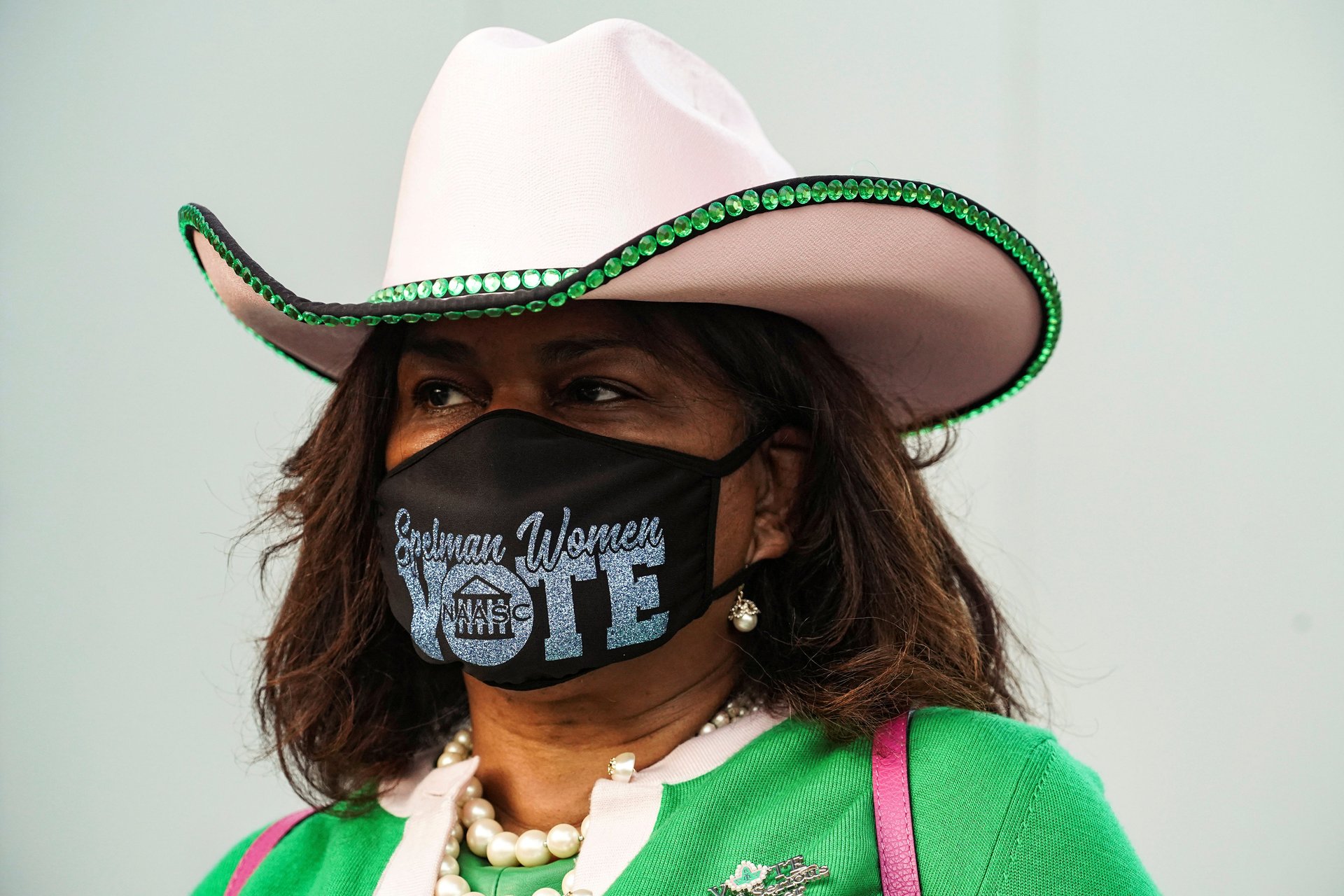

While the county encouraged voters to wear PPE at the polls and giving protecting material to poll workers, the says poll workers and voters don’t need to wear masks. This, in Debeauvoir’s eyes, constitutes a form of voter intimidation: People without protecting gear cannot be turned away from the polling station, which means they could discourage other voters from entering at the same time or staying in line with them.

She hopes that some shaming and peer pressure might persuade even the most stubborn anti-mask voter to respect the polling place safety recommendations.

She is less worried, however, about the so-called Trump army, the group mobilized by Donald Trump Jr. to show up at the poll to prevent alleged voter fraud. She thinks a lot of their tactic merely amount to threatening action online, and she doesn’t expect to see group of mask-less Trump supporters trying to get inside the polls and threatening voters or compromising their safety. In case that should happen, however, the sheriff has an intervention plan. “You can’t appoint yourself a poll watcher,” says Debeauvoir, and these groups would be breaking the laws if they tried to enter the polls without being voters.

Even in previous election, the about two thirds of voters in the county had preferred early voting over Election Day, and while Debeauvoir won’t predict whether an even higher percentage of voters will choose early voting this time. “I do think that we’re headed for record turnout and that would about 650,000 registered voters voting,” she said.

For instance, she reports, there have been more young voters. Austin is a college town with a large youth population, but while registering young people has not been a problem in previous year, the turnout of people 18 to 30 has historically been poor. This year, however, more people at the polls have announced themselves as first-time voters—something, Debeauvoir says, that is often met with a cheer from the other voters.

The current record for turnout in Travis County was set in the 2008 presidential election, when 77% of eligible voters cast ballots.