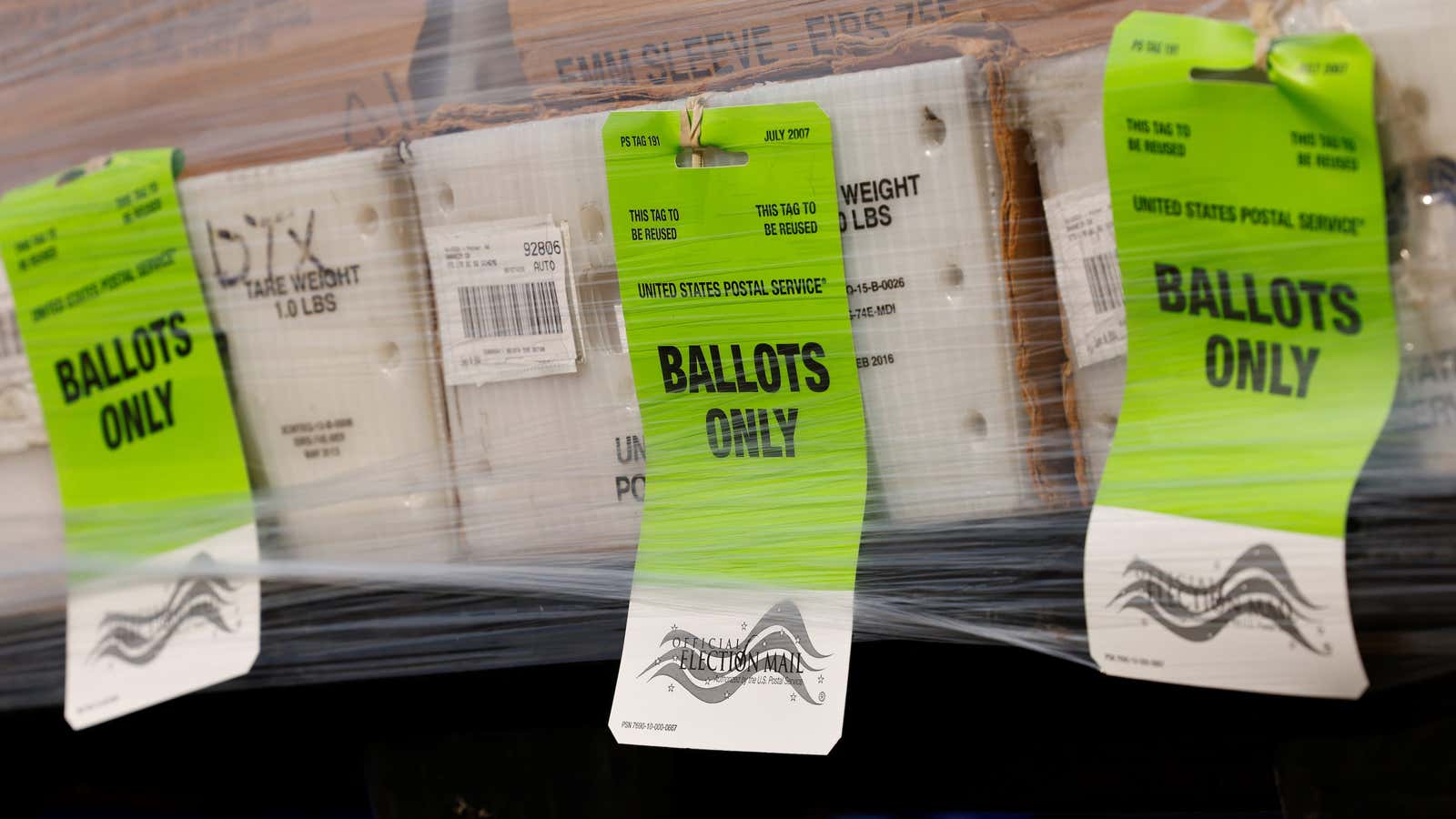

Even before a global pandemic made in-person activities complicated, a lot of Americans voted by mail. In 2016, nearly a fourth of all votes cast in the presidential election (33 million) were absentee. This year, it’s expected to be a lot more—around 80 million ballots are expected to arrive via mail.

But what happens to the mail-in ballot after it reaches the county’s election office?

As with everything with US elections, it depends on the state. This year, things are even more complex—regulations are still being changed as a result of a large number of lawsuits trying to either expand access to voting, or make it tighter, with more security measures.

Processing and tabulation

Once the ballots is received, it is recorded. The process of doing this might differ depending on the state and county. For instance, in Inyo County, in rural California, where an overwhelming majority of people are expected to vote by mail, the votes are first divided by how they reached the election office—either by mail, through a drop box, or brought to the election office by the voter. Ballots often have a barcode, so once each ballot has been processed, voters can check its status online.

In most states, signatures and addresses (which appear on the outer envelope containing another anonymous envelope with the ballots) are either checked as the ballots are received or starting on a specific date within weeks of the election. If the signature on the ballot is absent or doesn’t match the county records, the ballot is rejected.

Many states have an option to “cure” ballots with missing or mismatched information, so instead of being rejecting them right away, they contact voters seeking further information to see if the vote can be accepted. Voters who are tracking their ballots and see them rejected or challenged should contact their county office to learn their options.

Dawn Barger, the director of voter access at the US Vote Foundation, a nonprofit offering support and information to voters, says one thing is clear in talking to election officials across the country: They really want people to be able to vote, so they work hard to help voters cure the ballot, if it’s possible. “Election officials are doing everything they can,” she says.

Mismatched signatures are one of the most common reasons for ballots that arrived within the deadline to be challenged or rejected. Others are a failure to fill out the ballot correctly, or sending the ballot in the wrong envelope.

Storing and counting

Once ballots have been verified, three things can happen depending on the state: Ballots are opened, and prepared for counting; they are opened, and counted; or they are not opened until Election Day.

Whether they are prepared ahead of time or at the time of counting, the envelope containing the ballot is removed from the signed envelope in a way that ensures voter anonymity. Since the process is done by hand, it can be time-consuming and most election offices only have a handful of employees.

Kammi Foote, the clerk, recorder, and registrar of voters of Inyo County, says to keep up with the flood of ballots during election season, work hours stretch far beyond office hours.

The states that allow early counting do so at very different times—in some cases, weeks before Election Day, in others, only as the polls are opening. In all cases, ballots are kept locked in a dedicated location, on the premise of the election office or in another government building, until they are ready for the count. Counting takes place in a public forum, where an audience including volunteers, party representatives, and the media can verify the fairness of the process.

“I’m a temporary custodian [of the ballots],” says Foote, who emphasizes the importance of transparency in keeping the trust of voters, “but the voting process itself belongs to the people.”

Of course, being able to process votes ahead of polling day shortens the wait for results dramatically, and means the mail-in vote’s results—which are kept secret until the closing of the polls—can be revealed without great delay. This is especially important in swing states, which may decide the presidential election. This year especially, with the higher volume of mail-in voting, the wait for results might be long.

Currently, Georgia, Iowa, Michigan, Minnesota, Nevada, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin are states identified as key to the presidential election’s outcome where counting won’t start until election day (and in Wisconsin and Minnesota, it won’t begin until the closing of the polls).

A few states have a window of one or two weeks to accept ballots that are postmarked before the election but are received after, so they count those ballots then.

If absentee ballots delay the count, it can take weeks to get a final result, even without recounts. In any event, the final counts need to be in by the Monday after the second Wednesday in December, when the Electoral College meets in Washington to cast its votes. This election, that is December. 14.

After the count

Once they are counted, according to the law, all federal election ballots must be kept for at least 22 months. Local election boards are usually responsible for picking a safe storage location—typically a government warehouse, or a courthouse.

After the 22 months are passed, ballots may be destroyed. It’s up to the state to decide how, but only some—like Ohio—give detailed instructions on how to dispose of ballots. Typically, this happens either by shredding, or by sending them to a disposing or recycling facility.