Looking for signs of life in Ukraine’s shell-shocked financial markets

“The best rebuke to Russia is a strong and successful Ukraine.” This is how British prime minister David Cameron put it in a recent speech, laying out the West’s two-pronged approach to the crisis in Crimea: Slap sanctions on Russia and accelerate aid, loans, and trade agreements for Ukraine.

“The best rebuke to Russia is a strong and successful Ukraine.” This is how British prime minister David Cameron put it in a recent speech, laying out the West’s two-pronged approach to the crisis in Crimea: Slap sanctions on Russia and accelerate aid, loans, and trade agreements for Ukraine.

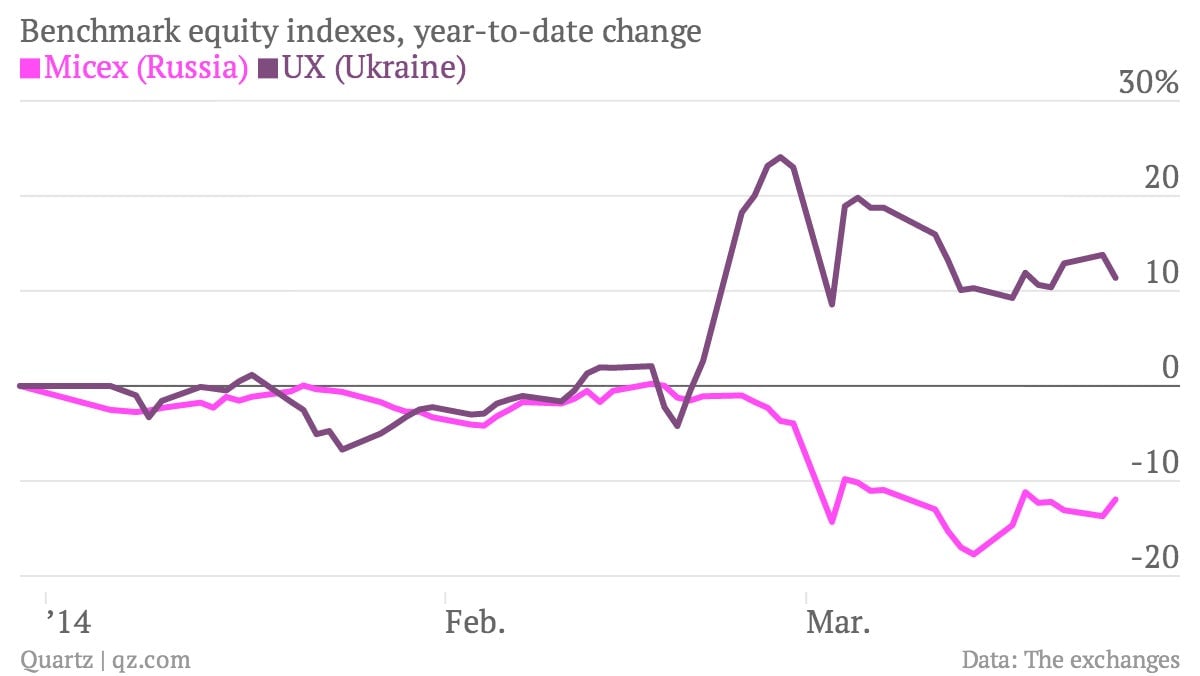

By one measure, this appears to be working—Ukraine’s main stock market index is up by more than 11% so far this year, one of the best performers in the world. Over the same period, Russia’s main domestic stock index has fallen by around the same amount:

But there are caveats. Ukraine’s financial markets are shallow and thinly traded. Bloomberg recently profiled a Kiev trader twiddling his thumbs due to the lack of interest in Ukrainian assets. For that matter, relative to the size of its economy Russia’s markets aren’t particularly deep either.

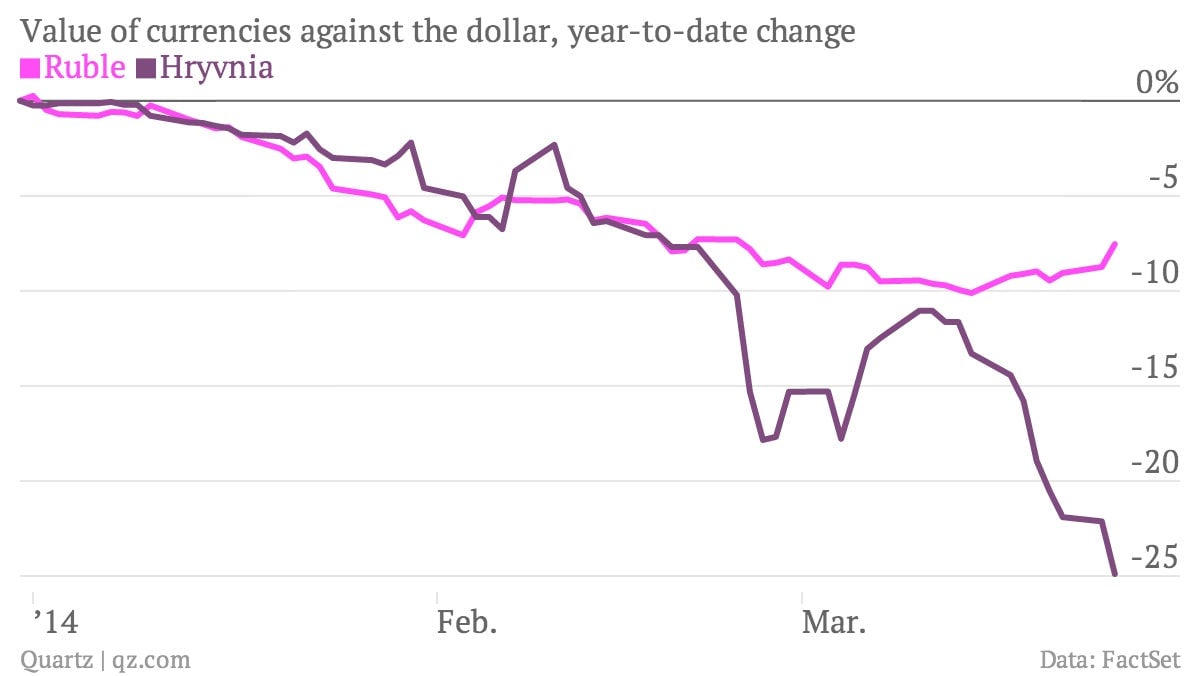

Investors are mostly pulling their money out of both countries. Capital flight from Russia has reached perhaps $70 billion so far this year and Ukraine’s central bank is preparing vague “measures” to stem the flow of funds out of the country. Foreign investors have been wary of local-currency assets in both countries during the best of times, so the recent turmoil is scaring away all but those with the strongest stomachs.

Moreover, for a foreign investor, the local stock-market performance in the chart above looks less enticing when you consider that the Ukrainian hryvnia has had a much rougher ride than the ruble in recent months. Russia’s considerable foreign reserves allow it to smooth its currency’s moves, a luxury that Ukraine’s dwindling coffers do not allow:

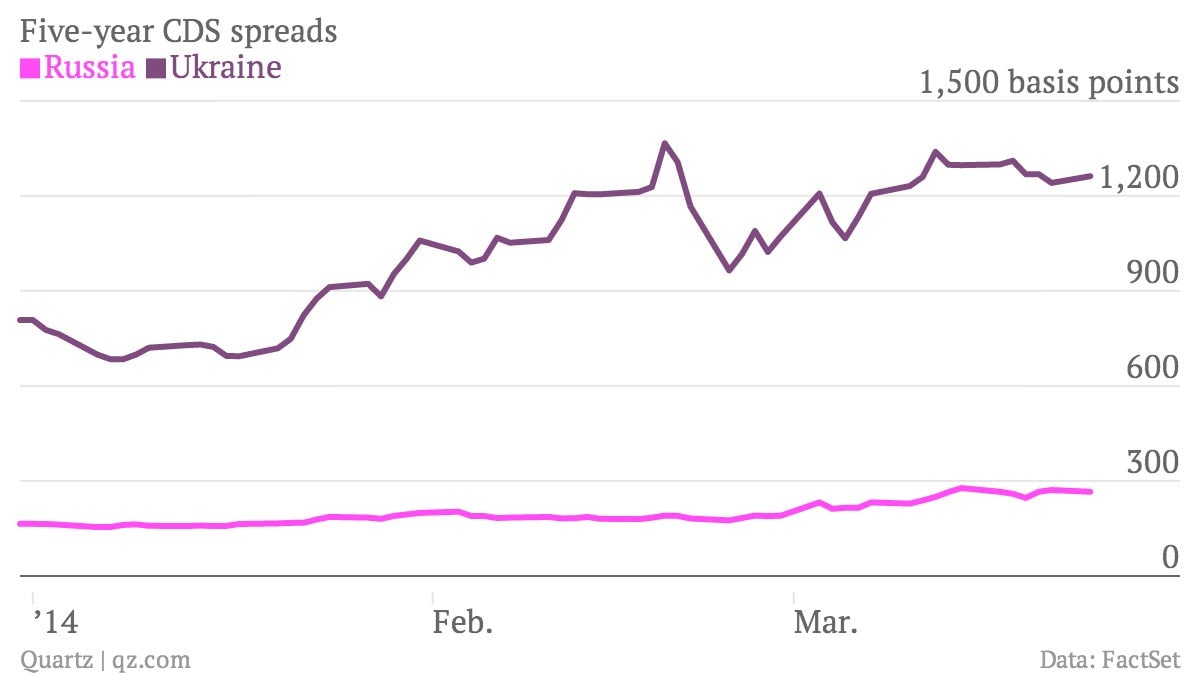

And on measures of default risk, the two countries are far apart; Ukraine is considered one of the world’s riskiest borrowers, according to credit-default swaps (the wider the spread, the higher the probability of default). Although Russia’s perceived creditworthiness has taken a hit in recent months, the markets are not particularly worried about it defaulting on its debts:

Ukraine’s economy will almost certainly shrink this year; the local unit of France’s BNP Paribas reckons that GDP will fall by 5% in 2014. Ukraine might renege on some of its debts to Russia, while Russia will probably hike its bill for gas piped to Ukraine. It is unclear how all of this will affect Ukraine’s fragile government finances.

Thaddeus Best, an analyst at Business Monitor International, reckons that Ukraine’s GDP will fall by just under 2% this year, but “the risks of complete economic meltdown are unfortunately still quite salient,” he tells Quartz. Western aid with few strings attached may tide the country over in the short term, but rehabilitating the Ukrainian economy is a long-term project with an uncertain chance of success. It’s an encouraging sign that some intrepid investors are betting on Ukrainian stocks, but this is only one faint sign of life in the country’s otherwise shell-shocked markets.