If the Electoral College can’t be abolished, can it be reformed?

For the second US presidential election in a row, the electoral college is under scrutiny.

For the second US presidential election in a row, the electoral college is under scrutiny.

When the results of the popular and electoral votes match, as they did for every presidential, election from 1892 to 1996, the electoral college feels like an anachronistic quirk of the system, the constitutional equivalent of a powdered wig or quilled pen. But when they are in opposition and the loser of the popular vote wins the election, as in 2000 and 2016, it feels much more threatening to the principles of democracy, which—in theory—is organized around majority rule.

No matter what the ultimate outcome this year, it’s likely the calls to abolish the electoral college will only get louder.

The idea has merit. After all, the US elects every other federal office through a popular vote. And no other democracy chooses its head of state this way. But abolishing it will be difficult, if not impossible, in part because the same power it grants to less populated states is also baked into the mechanisms required to get rid of it.

Like much of the Constitution, the Electoral College reflects its authors’ concerns about the power of direct democracy. While the concept of a democratic republic was based on enlightenment ideas, it was still an experiment when the Constitution was ratified in 1788. No other nation had really tried it, and the authors of the Constitution hedged their bets. The electoral college was designed to serve as a brake on direct democracy, to prevent the election of a demagogue and so “that the office of President will never fall to the lot of any man who is not in an eminent degree endowed with the requisite qualifications,” as Alexander Hamilton wrote in the Federalist Papers. (Whether it served that purpose in 2016 is another question).

The electoral college also represents a compromise to check the power of the biggest states. Just as the Constitution gives every state two senators, no matter its size, the electoral college gives more weight to smaller states. Its detractors say that’s a key flaw in the system, since residents of Wyoming and Vermont have much more voting power than citizens of New York and California (and not incidentally, it takes power from cities and states with more people of color). But its supporters say that’s a feature, not a bug, since it prevents rural areas from being swamped by urban voters.

Whatever your view, it’s clear that since two-thirds of the Senate is normally required to amend the Constitution, an amendment abolishing the Electoral College would have an uphill battle. It’s unlikely those smaller states would willingly surrender that political muscle.

Short of abolition, could the electoral college be modified to make it more representative? Perhaps, and it may be worth noting here that the Constitution was amended once before to fix flaws in the electoral college. Granted, that last happened in 1804, through the 12th Amendment, but there is precedent!

Here are some ideas for reforming the electoral college:

Expand the House of Representatives

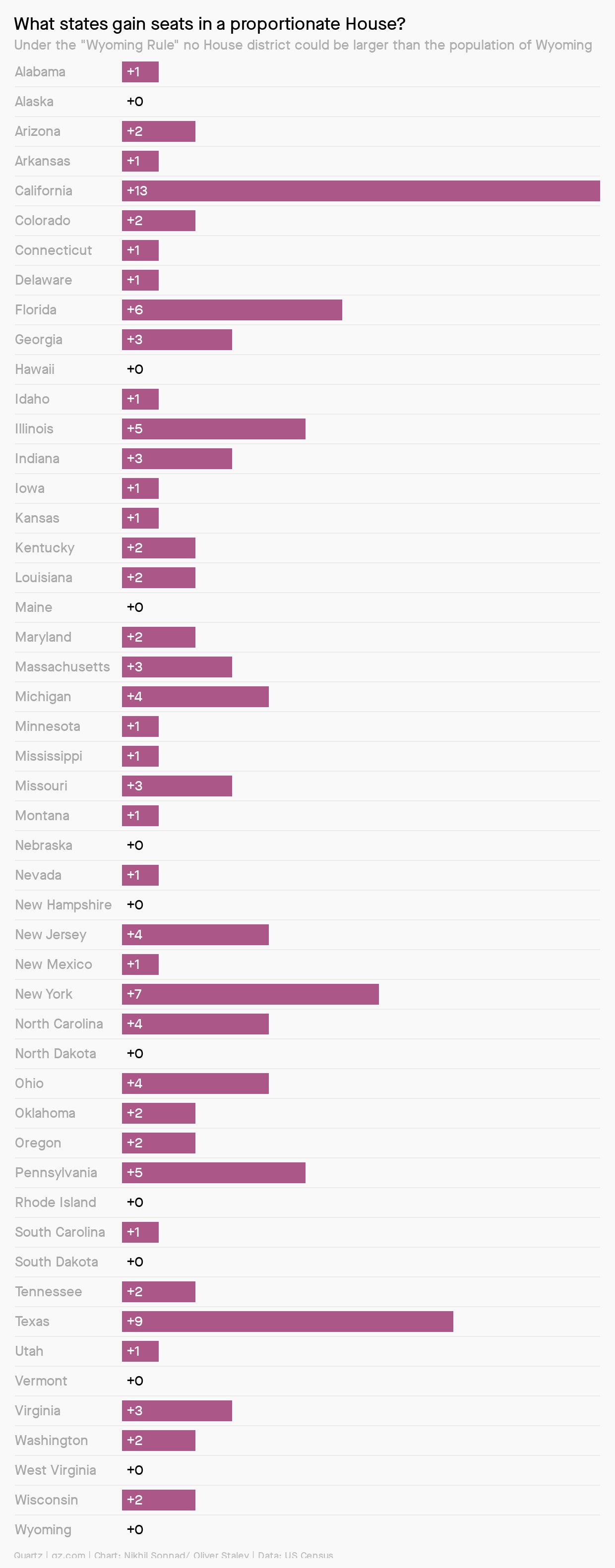

Since the Electoral College gives each state the number of electors equal to their number of senators plus representatives, one fix is to let the number of representatives increase with the population of the states. Since the number of House seats was last fixed at 435 in 1929, the country has grown disproportionately, with some states growing much faster than others. Under a proposal sometimes called the Wyoming Rule, the House could be expanded so the maximum size of every House district would be equal to the size of the smallest district—currently the entire state of Wyoming and its 563,626 residents, according to the 2010 census. Seats would be added until every state had proportionate representation.

Under this system, the House would grow to 545 Representatives, with California gaining 13 new seats and New York gaining seven. Notably, this system wouldn’t necessarily favor blue or Democratic leaning states. Texas, for example, would also grow by nine seats. But the weight of each state in the electoral college would be more closely aligned with its population.

Proportionate allocation

This option is deceptively simple: Instead of a winner-take-all race in each state, the state’s electors would be allocated in proportion to the number of votes captured. So if a candidates wins 60% of a state’s votes, they win 60% of a state’s electoral votes, rounded up to the nearest whole number. There would no longer be red and blue states since each state would have value for both candidates, and states like California and Mississippi would again be in play in presidential elections. While our current system counts a close victory the same as a blow out, proportionate allocation would mean even votes in losing efforts have value.

Because it works with the existing make up of the House and Senate, small states are still over weighted, and so the winner of the popular election could still lose. In his Crosstab blog, journalist G. Elliott Morris used this system to re-run every election since 1976. In almost all cases, Electoral College margins are much narrower, because candidates rarely win all of a big state’s electors. And while Hillary Clinton would have won with this method in 2016, Al Gore would still have lost in 2000.

The system would give new importance to third-party candidates, who would now gain electors. Consequently, there would be a far greater chance that no candidate would capture 270 electoral votes necessary to win the election. That means elections would be decided in the House of Representatives, which Morris notes, might be what finally kills the Electoral College.

A similar proposal would allocate electors to the winners of each congressional district, as Maine and Nebraska currently do. An analysis by FairVote, a non-partisan group that advocates for election reforms, however, shows that because of gerrymandered districts, allocation by congressional district would result in even more skewed election results.

Interstate popular vote compact

Under this system, states agree to allocate their Electoral College votes to the candidate who wins the popular vote. It has the benefit of working within the current Electoral College system, and takes advantage of an often-overlooked detail: The awarding of all electoral college votes to the state’s winner is a function of state law, not the Constitution (which is why Maine and Nebraska can do it differently).

Under the proposal, states legislatures would vote to award their electors to the winner of the popular vote of the whole country, regardless of how their state votes. So far, 15 states and the District of Columbia have agreed, meaning 196 electoral votes are pledged to the popular vote winner. If states with another 74 total electoral votes adopt the plan, then it would go into effect (and it has passed at least one chamber in nine additional states).

National Popular Vote, the bipartisan group behind the proposal, argues the current system does more than distort the will of the voters. It also means so-called battleground states receive disproportionate attention from candidates, as well as incumbent politicians looking to curry favor with their voters. Battleground states receive 7% more federal grants than “spectator” states, according to the group.

The interstate compact doesn’t amend or abolish the electoral college, and so if it were adopted, it means the old state-by-state, winner-take-all system could eventually return. But it also doesn’t require the heavy lifting of a constitutional amendment, and so it’s the closest of any proposal to becoming a reality.