Wu-Tang Clan is wrong: Music as an object is dead

Legendary hip-hop collective, the Wu-Tang Clan, has announced that its first new album for seven years will be released on a limited run of exactly one copy.

Legendary hip-hop collective, the Wu-Tang Clan, has announced that its first new album for seven years will be released on a limited run of exactly one copy.

In a statement the group’s leader and spokesman, the RZA, said that the 31-track, 128-minute opus, called The Wu—Once Upon a Time in Shaolin, will be put “on listening display in renowned galleries, museums, venues and exhibition spaces.” After that, the single copy (in an unknown format) will be sold in a hand-carved, nickel-silver box, designed by a British-Moroccan artist, Yahya, for what the group hopes will be a huge sum.

The Wu-Tang Clan is the latest in a series of artists to sell their music in unorthodox ways, following the collapse in sales of music in physical formats, and the failure of their digital successors to compensate. Prince broke the mold in 2007 by signing a deal to give away his latest release with a UK newspaper, Radiohead offered up their In Rainbows album on a pay-what-you-like basis several months later, while in 2013 Samsung paid Jay-Z to have 1 million copies of his Magna Carta Holy Grail album given away to purchasers of its latest handsets, 72 hours before its official release. The novelty factor meant that each of these artists are thought of have earned at least as much as they would have done had their followed a traditional approach, helped by plenty of publicity.

The Wu-Tang Clan’s approach is likely to do the same. But the group’s ambition is greater. It also released a manifesto, which demonstrates that its single-copy strategy is intended to be a political statement as much as it is a publicity stunt. It argues that mass reproduction has devalued music, especially in comparison with visual artists, and by harking back to a “Renaissance-style approach” it hopes to drive up perceptions of what music is worth. The group say it is prepared to sacrifice the “pride and joy of sharing music with the masses” in favor of “reviving music as a valuable art.”

Allusions to the Renaissance and its patrons suit an outfit like the Wu-Tang Clan, who has always run a neat line in self-mythologizing. But the one-copy concept is not as revolutionary as the group would like. Although the price paid for the album is likely to be in the millions of dollars, it will be dwarfed by what the group will earn from its planned listening events. With tickets priced at a similar point to a major art exhibition, the play-backs will attract hundreds of thousands of fans around the world and will generate many times the value of the single copy. This means that the group’s approach will fit in with the existing pattern of musicians relying on events for an ever-increasing proportion of their earnings.

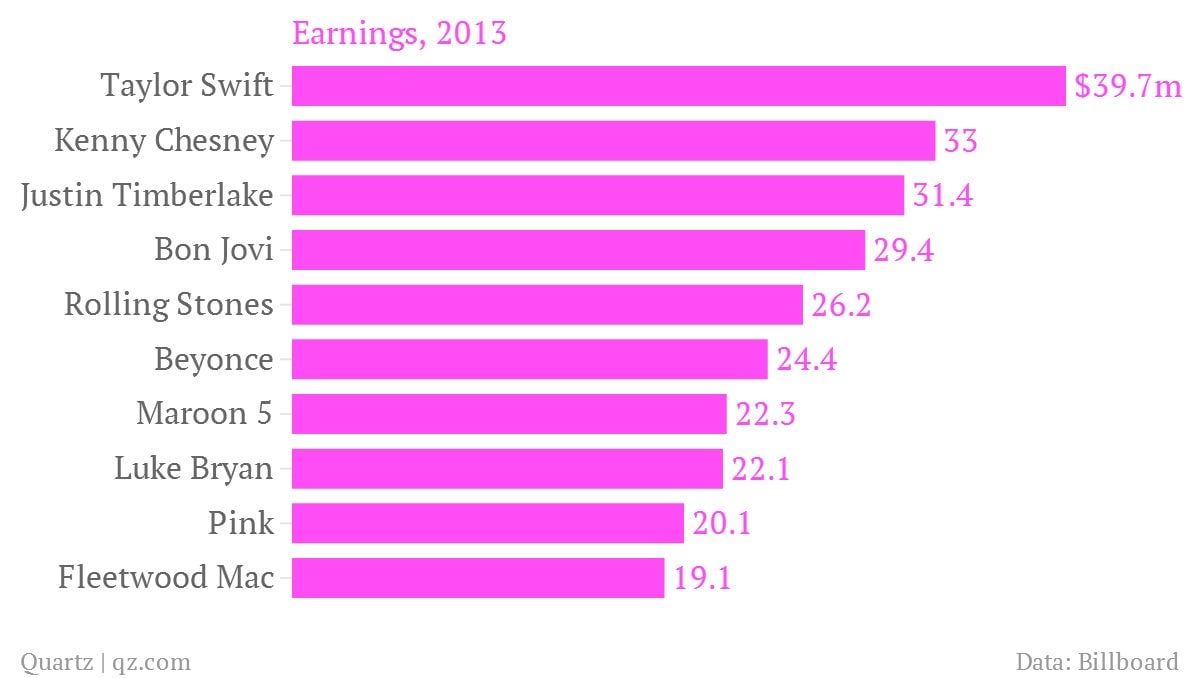

This trend was borne out by Billboard magazine’s latest list of money-making musicians, which was led, in 2013 by country-pop behemoth Taylor Swift. Of Swift’s estimated earnings of $39.7 million, fully $30 million was earned through her six-month tour in support of her Red album. This is not to suggest that sales of her music itself were slack. She was ranked eighth for physical sales, sixth for digital downloads and fifth for streaming revenue. But in today’s music economy, the latter trio are together worth only one-quarter of a big US tour. What’s more, Billboard estimated that Bon Jovi (fourth on the list) earned four times as much from online merchandise as they did from downloads and streaming combined.

What the Wu-Tang Clan claims it wants to revive is the commissioning of artists by wealthy patrons to create new music for their private use. Yet this would be contrary to the entire direction of the industry. Music is still consumed voraciously around the globe, but fans no longer queue at the record store to buy a new release; that anticipation now belongs to the day when tickets for the latest tour go on sale. More than ever, music consumption is a communal experience, and that means that physical formats are dead when it comes to making the big bucks.