America’s wildfires might make Covid-19 worse

In 2018, California had just endured the worst fire season in its history. More than 1.7 million acres burned. These wildfires are the “new abnormal,” said Jerry Brown, California’s former governor, at the time.

In 2018, California had just endured the worst fire season in its history. More than 1.7 million acres burned. These wildfires are the “new abnormal,” said Jerry Brown, California’s former governor, at the time.

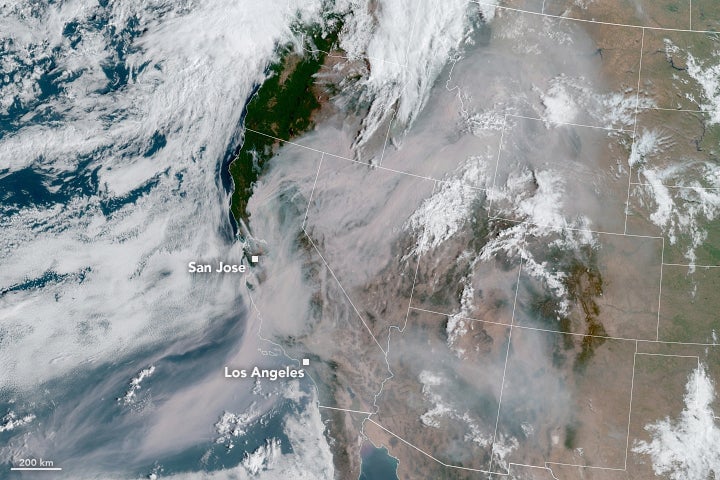

Just two years later, California endured its worst fire year again. Three of the four largest fires in state history occurred this year, burning more than 4 million acres, roughly double the area burned during the entire decade between 2001-2010. In September, many cities on the west coast were plunged into noon-day darkness as the air quality sank to unprecedented lows, blanketing much of the western US in a layer of smoke.

We’re still learning the price on Americans’ health. And the toll is likely to be higher during the Covid-19 pandemic, as wildfire smoke raises the likelihood of more severe respiratory infections.

Wildfire smoke exposures, once acute, are now becoming chronic across much of the west. Since the 1980s, the wildfire season has lengthened by two months, while the forest area burned has doubled, fueled in part by climate change. That’s sent a toxic miasma of soot, ozone, and other particulates deep into the lungs of millions of Americans.

“Wildlife smoke is like tobacco smoke without the nicotine,” says John Balmes, a physician and epidemiologist at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF). “Inhaling those particles causes similar harm.”

Public health officials are used to responding to short-term air-pollution events. America’s air quality index (AQI), devised by the US Environmental Protection Agency in the 1970s, is built on the assumption that bad air is temporary. It offers a simple way to measure risk over a 24-hour period based on exposure to six pollutants. But weeks of bad air make that number irrelevant.

“You can’t extrapolate this to a year-long event, even a few weeks is too long,” says Neeta Thakur, a pulmonary care physician at UCSF who studies the effect of air pollution on children and vulnerable populations.

And this year was unprecedented for the duration and intensity of wildfire smoke. For several days, the state recorded some of the worst air pollution on the globe. Air quality in the state’s interior and southern California was 10 to 15 times above federal health guidelines. In the Bay Area, health officials issued daily air alerts for a solid month between Aug. 18 and Sept. 16 advising vulnerable populations against going outside or breathing the air, a new record. More than 1,200 people likely died in California as a result of polluted air, estimate researchers at Stanford University.

“We’ve never had a month of this kind of air quality before by far,” says Aaron Richardson of the Bay Area Air Quality Management District. “It’s new terrain.” Normally, the agency focuses on protecting the most vulnerable populations, but this year, health officials were warning everyone of acute and long-term health effects. “It’s hard to tell with months-long exposure, which we’ve never had before,” says Richardson. “There will need to studies about the long-term effects.”

The Covid-19 connection

This comes at a particularly bad time as the Covid-19 pandemic ravages the globe. Air pollution initiates a cascade of inflammation in the lungs and cardiovascular system that increases the risk of severe coronavirus infections for people with pre-existing conditions such as asthma, high blood pressure, strokes, or heart disease. The consequences are already lethal: Each year, the World Health Organization estimates, 4.2 million people die as a result of breathing polluted outdoor air.

Air pollution is known to exacerbate lung infections such as pneumonia and influenza. Health officials worry the fires will worsen the Covid-19 epidemic in the US. Inflammation and oxidation in the lungs from smoke exposure makes it easier for lung infection to take hold and increase in severity, even weeks or months later.

“It’s not so much the risk of getting an infection, it’s that the infections are becoming more severe,” says Balmes. “The strongest evidence is for asymptomatic coronavirus to become more severe Covid-19 cases.”

Even small increases in particulate concentrations (10 μg/m3) can increase the odds of acute respiratory infections. In China, patients with SARS, a severe acute respiratory syndrome caused by a different coronavirus, were twice as likely to die if they lived in regions with very poor air quality, according to a 2003 study in the journal Environmental Health.

For Covid-19, the preliminary data are not encouraging. In the US and Italy, researchers also found that “chronic exposure to air pollutants impairs recovery and leads to more severe and lethal forms of the disease.” In China, “significant positive associations” were found between concentrations of major air pollutants and confirmed Covid-19 cases in 120 Chinese cities.

One salutary effect of the pandemic on respiratory health: In the early days of the outbreak, China’s quarantine procedures caused a plunge in air pollution from factories, cars, and other emissions sources. The drop was so dramatic, say researchers in the British medical journal The Lancet, that preliminary estimates suggest the reduction in deaths from cleaner air may outweigh China’s 4,633 deaths as of May.

In the US, that will be not the case. Air pollution levels have barely budged, while the coronavirus was never successfully contained, leading to 250,000 deaths and counting. For now, it’s too early to say exactly how much the wildfires will impact the severity of the pandemic. “We’re worried wildfire smoke may be enough to add fuel to the fire of Covid-19,” says Balmes.