China has begun its first prosecution of a coronavirus citizen journalist

Update, Dec. 29, 2020: Zhang was sentenced to four years in prison by a Shanghai court on Dec. 28.

Update, Dec. 29, 2020: Zhang was sentenced to four years in prison by a Shanghai court on Dec. 28.

In the early days of the coronavirus pandemic, citizen journalists in China were a vital source of first-hand information in a country where freedom of speech is heavily curtailed. Yet soon many disappeared into China’s opaque judicial system, and the first has now been formally charged.

Zhang Zhan, who was detained in May, is accused of “picking quarrels and provoking troubles,” a catch-all allegation commonly levied against activists in China. The Shanghai public prosecutor’s office said that Zhang had published “a large amount of false information” in videos and writing through WeChat, Twitter, and YouTube since Feb. 3, when she arrived in Wuhan, according to an indictment provided by Zhang’s friend Li Dawei.

“Zhang also accepted interviews from foreign media outlets like the Epoch Times and Radio Free Asia to maliciously hype up the situation in Wuhan, reaching a wide audience and causing a negative impact,” the indictment, dated Sept. 15 but posted by Li online on Nov. 13, said. The prosecutor’s office, which didn’t reply to a request for comment, is recommending a sentence of four to five years.

In China, citizen journalists are rare because they can’t obtain the official accreditation required to report news. But amid increased public anger against authorities due to the belief they suppressed information about the new disease—in the early days of January, doctors who shared information about a cluster of unexplained respiratory illness were harassed by police—several traveled to Wuhan. From the epicenter of the coronavirus at the start of the pandemic, they tried to document the situation for people in China and the outside world.

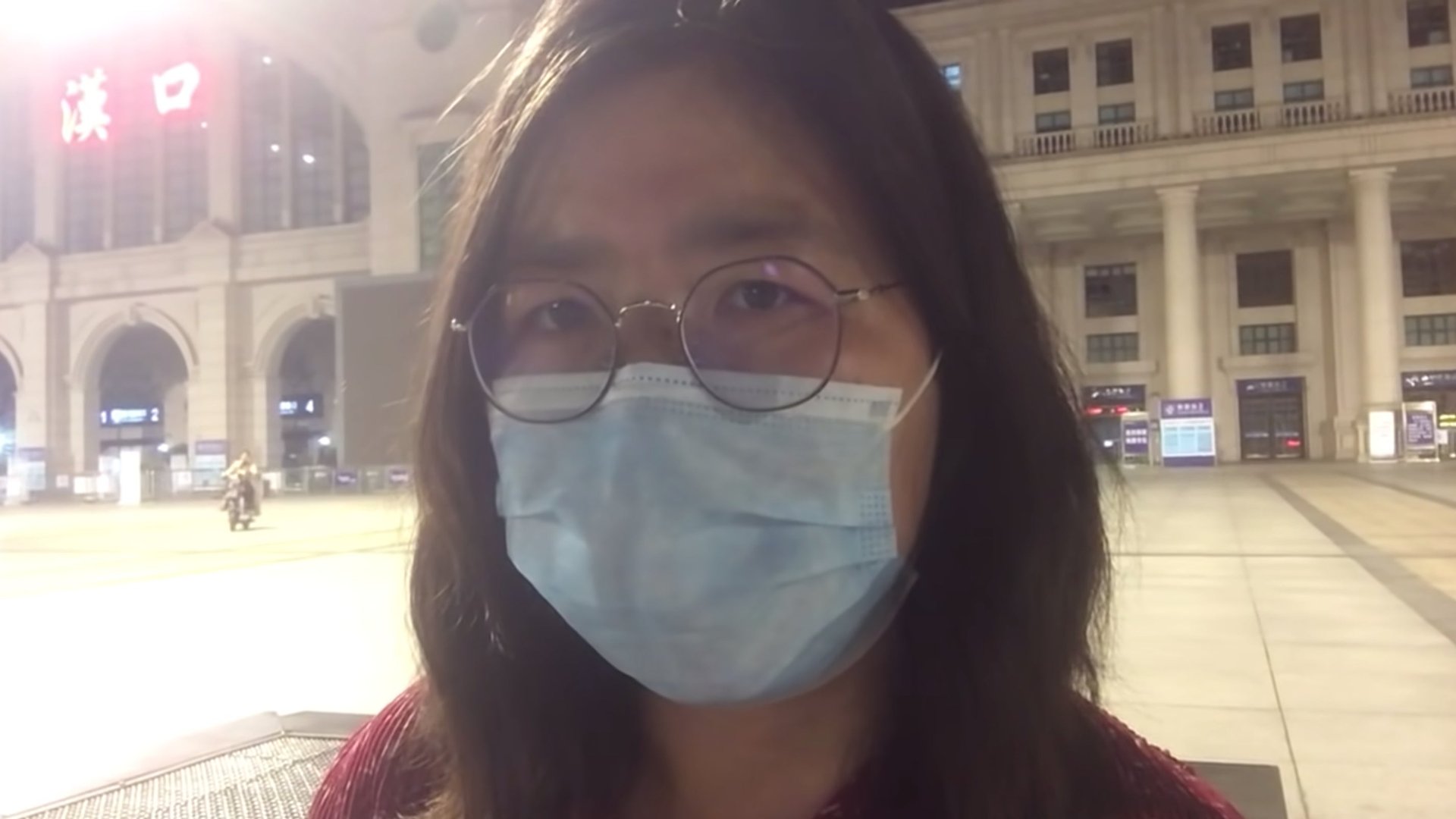

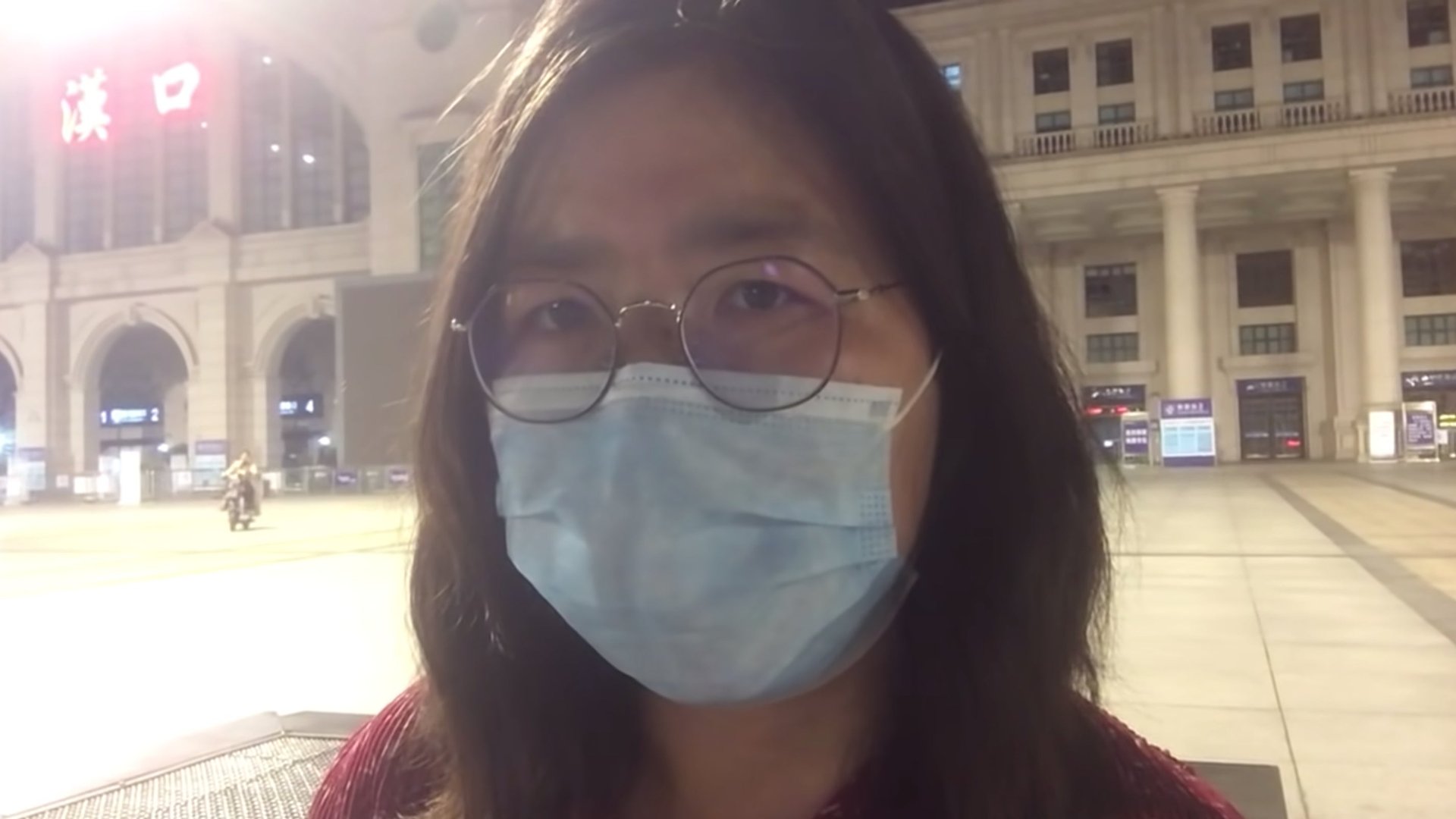

Zhang, for example, posted 11 videos on YouTube about the situation in Wuhan, showing city’s empty train station and streets, as well as her clashes with local police who asked her what she was doing. She also criticized the Wuhan government’s treatment of coronavirus victims, including a mother who was seeking justice (video) for her daughter who contracted Covid-19 during her stay at a local hospital in mid-January, when the government had yet to admit that the virus could be transmitted human-to-human. Her daughter eventually died of the illness.

Three other citizen journalists—Chen Qiushi, Fang Bin, and Li Zehua—all disappeared in February as soon as their coverage of Wuhan during the pandemic started to gain traction online. Li Zehua resurfaced in April, saying he had been taken by police on suspicion of disturbing public order but was later released as the authorities did not press charges. Meanwhile, Chen and Fang’s whereabouts still aren’t known, though Chen is reportedly staying under home surveillance at his parents’ house. A friend who runs Chen’s Twitter page, and has been updating the account regularly to keep attention on Chen’s disappearance, was unable to get in touch with Chen to confirm that he is indeed under house surveillance.

In part, dissatisfaction with the information available from the government drove Zhang, a former lawyer, to take such risks, her friend Li explained, and so did her personal beliefs.

“As a committed Christian, Zhang thought it was her responsibility to tell people what was really happening in Wuhan. She visited the tombs of those who died of coronavirus and even went to local crematoriums to check whether the official death statistics were accurate. She took huge risks in doing those things,” said Li.

Wang Jianhong, a UK-based human rights activist, said her major worry is whether the authorities will put Zhang on trial secretly.

“Zhang’s case has had a huge international impact, which makes it even less likely for the authorities to open the trial to the public in order to avoid criticism…As long as Zhang no longer has a voice, she will not be seen as a threat to them,” said Wang, who initiated an online campaign to advocate for Zhang’s release. “The world hasn’t paid enough attention to this heroine.”

It’s nearly impossible to find Zhang’s writing or videos in China now, but some traces of her have slipped past censors to remain online.

“Where is Zhang Zhan? Wuhan remembers you,” wrote a user on China’s Weibo platform in May. Another post responded on Nov. 15, six months after Zhang vanished from the public sight, “She was just sentenced to jail.”