The Japanese will keep hunting whales, even though they’ve lost their appetite for them

The International Court of Justice just ordered Japan to temporarily stop killing whales in the Antarctic, calling Japan’s bluff on the “scientific research” behind whale hunts that kill nearly 1,000 whales there a year. In other words, it ruled that hunting and killing whales, then selling their meat at a loss to public schoolchildren and at bargain-basement prices in grocery stores isn’t science.

The International Court of Justice just ordered Japan to temporarily stop killing whales in the Antarctic, calling Japan’s bluff on the “scientific research” behind whale hunts that kill nearly 1,000 whales there a year. In other words, it ruled that hunting and killing whales, then selling their meat at a loss to public schoolchildren and at bargain-basement prices in grocery stores isn’t science.

That’s a big deal. But while the ICJ’s decision will halt the ¥795 million ($9.94 million) Antarctic “research” operations of Japan’s Institute of Cetacean Research (the non-profit that runs the hunts), Japanese whale-hunting will continue. The government still invests ¥715 million in its whaling activities in the north Pacific.

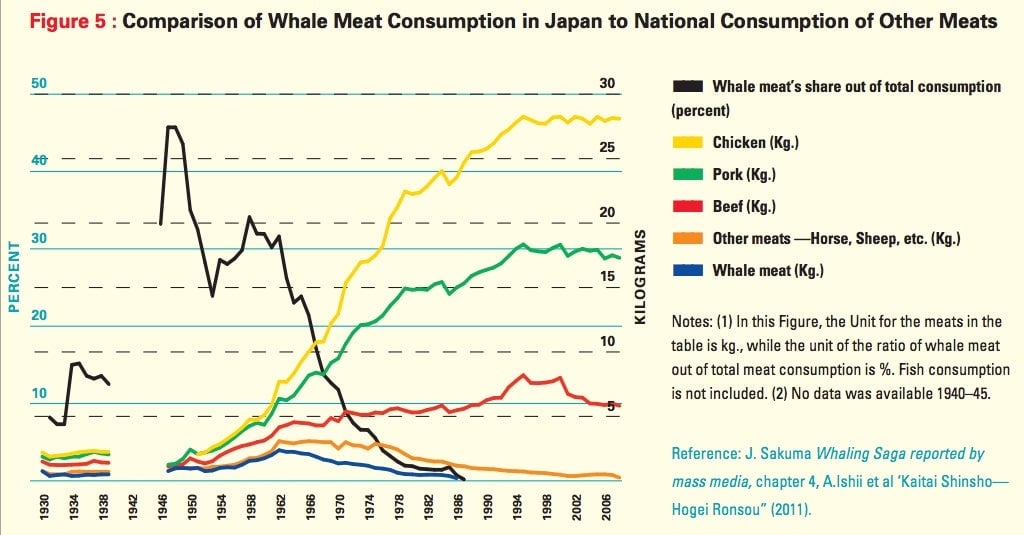

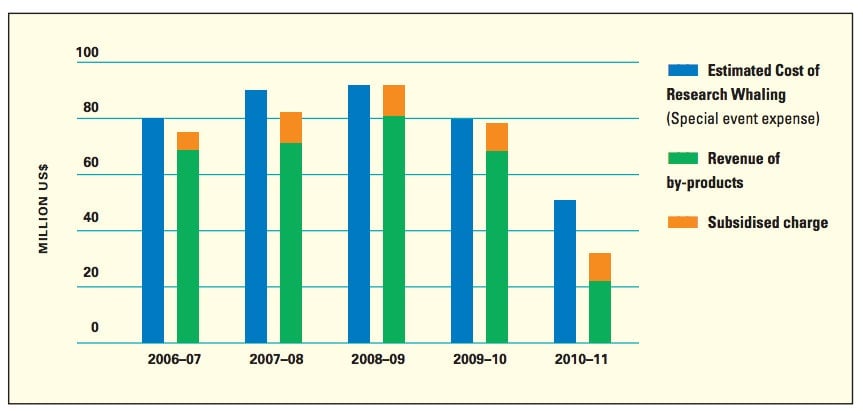

This is but the latest blow to Japan’s whaling program, which has long been struggling. ICR sold only ¥2 billion in whale meat last year—down from ¥7 billion in 2004—even as the government is expected to inject ¥5 billion in total this fiscal year, reports the Associated Press. The problem? Fewer and fewer people want to eat whale meat. Once a common dish in postwar Japan, demand has since fallen sharply, as the Japanese public finds it increasingly unappetizing. The meat is now mainly consumed in specialty restaurants, schools and in a few coastal whaling towns.

But even as stockpiles of the meat in Japanese ports continue to rise, hitting 4,600 tons (4,173 tonnes) in 2012, up from less than 2,500 tons a decade earlier, the industry refuses to give up. The ICR’s latest marketing tack is to promote the meat as “a nutritious food that enhances physical strength and reduces fatigue.” In a desperate bid to cover the mounting debts of ICR’s whaling program, the Japanese government shunted some $23 million earmarked for disaster recovery after the Fukushima earthquake/tsunami in 2011.

So why bother fighting for whale hunting? As a simple matter of supply and demand, ICR’s operations make no sense. But through a different lens they do. The government’s whaling program probably has more to do with defending territorial rights and claims to the abundant marine resources of the Antarctic than with any real appetite for marine-mammal flesh. As Patrick Ramage, the whale program director for the International Fund for Animal Welfare (IFAW), told Quartz last year:

“Along with the whaling issue, [the Japanese government is strongly opposed to issues like] the management of tuna fisheries, international proposals to protect sharks or even polar bears that come up at relevant international meetings—even if they don’t have a direct interest…. Unfettered access to marine resources on the high seas matters a lot to you if you’re a Japanese decision-maker.”

If ICR’s program is indeed a placeholder activity for asserting those territorial rights, whale-hunts are unlikely to become a thing of the past just yet.