In case it was unclear, the Chinese government does want the economy to keep growing—and at 7-plus percent, to boot. That’s apparent in premier Li Keqiang’s announcement today of fresh measures (paywall) to stimulate the economy. Those include accelerating railway construction, building housing for the poor, and cutting taxes for small businesses.

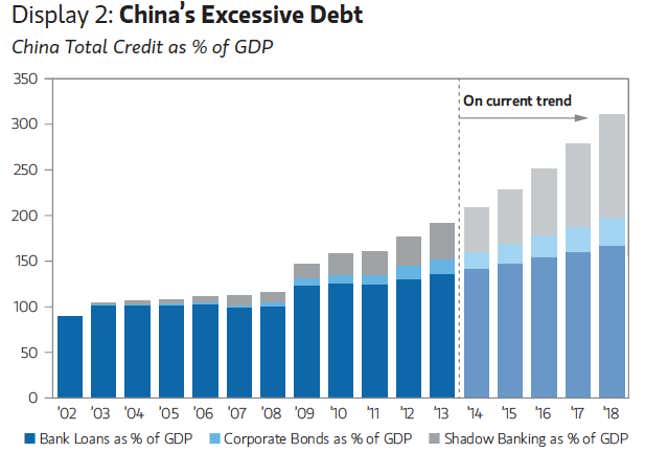

It remains unclear, however, who will foot the bill. China’s private sector debt is now nearly 200% of its GDP, according to Morgan Stanley calculations. The government wants banks to fund the construction, though the central government or its proxies will also issue bonds—which some hail as a sustainable means of finance.

Debt, however, is still debt—and the more China has, the riskier things get. Building railroads and public housing is much more ethically comforting than, say, propping up coal mines. But neither generates much, if any, cash—hardly the definition of “sustainable.” Government funding of these projects might juice GDP for a quarter or two, but that investment comes at the expense of other policy choices that might be more productive in the long run. Foremost among these is the government’s artificially low rigging of the deposit rate, which keeps borrowing cheap, though it comes at the cost of household consumption.

So why are Li and his leadership circle choosing to throw more borrowed money at projects that don’t generate value, instead of instigating that much-discussed interest rate reform?

Perhaps because, thanks to a half-decade investment binge, there’s simply aren’t any projects that generate value left to invest in. According to calculations by Wei Yao, economist at Société Générale, to generate each yuan of GDP, the country now must invest nearly twice what it did five years ago. Where is the rest of that credit going? To pay off the interest on existing debts or to invest in projects that don’t generate money.

This is grimly apparent in a must-read piece (registration required) today by Anne Stevenson-Yang of Beijing-based J Capital Research. She reports that shadow-market institutions can’t find projects to invest in because the quality of borrowers is “dismal.” Banks, meanwhile, are shifting their lending to off-balance-sheet vehicles because they deem it too risky to hand money over to third-party trust companies.

The Communist Party, says Stevenson-Yang, ably controls the top three tiers of the economy—the finance ministry and central bank; the state-owned banks; and the big state-owned enterprises (SOEs). However, the private economy is sputtering, she says, citing the examples of an equipment-financing company in Xinjiang whose orders are down 75% since 2010, and of Guizhou liquor distributors who say 70% of the province’s liquor factories have shuttered.

These are worrying signs for the Chinese economy, and they’re not problems that can be fixed with a dollop more of debt-bought steel and cement. It’s hard to tell which is a more disquieting scenario: that the government’s investment trick is no longer working, or that it has finally run out of tricks, but doesn’t realize it.